Maintaining Oral Health in our Companion Animals

The treatment of periodontal diseases in dogs and cats.

This course was published in the November 2009 issue and expires November 2012. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Understand the development and progression of periodontal diseases as they occur in dogs and cats.

- Discuss differences in planning and delivery of dental treatment in veterinary offices.

- Make appropriate suggestions for active and passive products that help prevent the development of periodontal diseases in dogs and cats.

Periodontitis is the most commonly diagnosed disease in dogs and cats among small animal veterinary practices.1 By the age of 3 years, approximately 75% of dogs and 60% of cats have some type of the disease.2 As in humans, the primary risk for animals with periodontal diseases is tooth loss, but they may also experience systemic effects such as bacteremia.3,4 The mechanisms of action in the development and progression of periodontitis are most likely the same as in humans, with bacterial virulence factors and host response playing significant roles. The bacterial species involved in the development of periodontitis in humans—Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis—are not significant in the development of periodontitis in dogs. Recent studies of dogs with active periodontitis found 26 different species of black-pigmented anaerobic bacteria among test subjects with the most prevalent being Porphyromonas salivosa, Porphyromonas denticanis, and Porphyromonas gulae. These species accounted for 50% of the isolates cultured.5

ON THE PATH TO GOOD ORAL HEALTH

The most common complaint among clients regarding their pets’ oral health is malodor.1 Both dogs and cats tend to be stoic in their tolerance of dental pain until it is well advanced. Clients can positively impact the oral health of their pet by doing routine visual inspections at home (Figure 1 shows the healthy gingiva of a dog) and by having professional evaluations at each wellness examination. This should start with the first puppy or kitten examination and continue throughout the life of the pet.

Initially, the patient is visually examined for malocclusions and persistent deciduous teeth as well as the level of plaque and calculus formation. As in humans, accumulation of deposit and each patient’s gingival response to plaque bacteria vary. Certain small and toy breed dogs, eg, dachshunds and Yorkshire terriers, tend to develop periodontal diseases more easily with rapid progression.6 These patients require a firmer commitment from the client to both plaque control at home and more frequent professional periodontal treatments done in the veterinary office. The timing of the first prophylaxis for both dogs and cats should coincide with their individual level of plaque and calculus accumulation. Dental anatomy and morphology in both dogs and cats increase the progression of periodontal diseases with normal furcations occurring closer to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) than in the human dentition.7

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Periodontal treatments, as well as any other dental procedures, need to be performed under general anesthesia, which increases the risk of medical complications and cost to the clients. Once it is determined that a prophylaxis will be beneficial, a thorough examination is done under anesthesia, including a fullmouth series of radiographs, full-mouth periodontal probing, and intra- and extra-oral soft tissue examination. Although full-mouth dental radiographs are not always obtained in veterinary practices they are an invaluable tool for diagnosing hidden lesions. A study at the University of California, Davis, showed that 28% of dental lesions in dogs and 42% in cats are missed on visual examination alone.8,9

Full-mouth periodontal probing should include an assessment of pocket depths, attachment loss, bleeding on probing, furcations, recession, and mobility. Normal periodontal pocket depths are dependent on the size of the patient with = 2 mm to 3 mm being within normal limits for a medium-sized dog and = 0.5 mm to 1.0 mm being within normal limits for a cat. The periodontal examination in conjunction with full-mouth radiographs provide the tools necessary to diagnose the presence of vertical and horizontal bone loss, the extent of furcation involvements, and widening of the periodontal ligament space.

Caries occurs infrequently in both cats and dogs. Cats do, however, experience two unique conditions: feline resorptive lesions and chronic stomatitis.10-12 Feline resorptive lesions typically begin at the CEJ as small pinpoint lesions and progress until the entire crown and root are compromised. The gingiva adjacent to a resorptive lesion will have an erythematous and edematous appearance as the tissue responds to the plaque retentive concavity of the underlying resorptive lesion on the tooth. These lesions may be localized to one affected tooth or present on several affected teeth with or without concurrent generalized gingivitis or periodontitis. Chronic stomatitis is a diffuse mild to severe inflammation of the nonattached oral tissues, most commonly occurring in the caudal (posterior) vestibular area lateral to the palatoglossal folds. Both feline resorptive lesions and chronic stomatitis are painful conditions with sequelae that can be confused with periodontal lesions and need to be assessed carefully by knowledgeable clinicians.

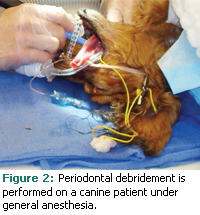

Patient positioning during treatment is decided by the personal preference of the clinician but is also limited by the constraints of the placement of the endotracheal tubes and intravenous lines for the administration of anesthetic gases and medications during general anesthesia (see Figure 2). In addition, care must be taken to avoid disturbing monitoring devices. In general, patients are placed in sternal, lateral, or dorsal recumbency and are repositioned several times during a series of fullmouth radiographs. Once radiographs have been completed, the remainder of treatment is rendered in either dorsal or lateral recumbency. Endotracheal tubes are cuffed to prevent aspiration of liquids, and pharyngeal packs made of gauze are used as an extra precaution.

Patient positioning during treatment is decided by the personal preference of the clinician but is also limited by the constraints of the placement of the endotracheal tubes and intravenous lines for the administration of anesthetic gases and medications during general anesthesia (see Figure 2). In addition, care must be taken to avoid disturbing monitoring devices. In general, patients are placed in sternal, lateral, or dorsal recumbency and are repositioned several times during a series of fullmouth radiographs. Once radiographs have been completed, the remainder of treatment is rendered in either dorsal or lateral recumbency. Endotracheal tubes are cuffed to prevent aspiration of liquids, and pharyngeal packs made of gauze are used as an extra precaution.

Time is a significant factor for dental procedures performed in the veterinary practice. Typically, all diagnostic information is collected and all periodontal and general dental treatment are performed at the same appointment.

PERIODONTAL THERAPY

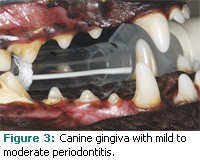

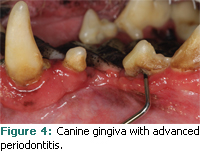

Once the diagnostic data have been obtained, the periodontal status of each tooth is graded according to the American Veterinary Dental College stages of periodontal disease (Table 1). The patient’s overall health and medical history influence the treatment planning considerations of safe length of anesthesia time, nonsurgical periodontal treatment (scaling), and other operative procedures. Teeth diagnosed with moderate to severe periodontitis (see Figures 3 and 4), furcation involvement, and mobility are routinely extracted.

Gross scaling and fine scaling are accomplished through the use of sonic and ultrasonic power scaling instruments. Because it is technically demanding, hand instrumentation is rarely used in general veterinary practice. Dental hygiene functions are typically delegated to veterinary technicians, who are trained to provide dental radiographs, prophylaxis, and simple extractions. There is no position in veterinary medicine analogous to the registered dental hygienist. Advanced nonsurgical periodontal therapy, periodontal surgery, and advanced dentistry can be referred to veterinary dentists who have undergone post-doctoral residencies. The numbers of these specialists are few, with currently less than 100 board certified in the United States.13 However, dentistry is a recognized veterinary specialty and an important emerging facet of the profession, so these numbers will most likely grow.

The goal of routine periodontal treatment and periodontal debridement therapy in veterinary practice is to remove supragingival and subgingival plaque and calculus deposits followed by selective polishing in an effort to minimize active inflammation and create an environment conducive to healing. Even though periodontal therapy is provided under general anesthesia, the use of regional anesthesia may be used to increase patient comfort both during treatment and post-operatively. The nerve pathways and anatomical structure of dogs and cats are similar to humans, so infraorbital and inferior alveolar nerve blocks are a frequent adjunct to general anesthesia.

Because cats and dogs have an increased sensitivity to fluoride, its use is generally contraindicated except in the rare case where caries is present.14 Because it is unreasonable to expose a veterinary patient to the risks of additional general anesthesia, re-evaluation of the success of periodontal treatment with periodontal probing is not possible. Re-evaluations are performed by visual observation instead. Professional care frequencies are determined by plaque and calculus formation, individual patient predisposition, client values, and the level of oral hygiene provided at home.

Chlorhexidine gluconate is frequently prescribed as a mouthrinse post-operatively and for patients with unresolved inflammation at the re-evaluation appointment.15

Two products with limited evidence of efficacy are barrier sealants and the porphyromonas vaccine.16,17 Barrier sealants are inert waxy barriers applied to the cervical margins in the veterinary office. Clients then follow up with weekly applications of plaque prevention gel. The porphyromonas vaccine uses killed bacteria to target P. denticanis, P. salivosa, and P. gulae, the three most prevalent bacteria found in the periodontal pockets of dogs. While there is some literature published based on rodent studies, no current data exist on the long-term efficacy of the vaccine in dogs.16

ACTIVE HOME ORAL CARE

Unlike human dentistry where periodontally compromised teeth are often kept for years through a combination of frequent professional care appointments and good oral hygiene, teeth considered to have moderate to severe periodontal involvement are routinely extracted in veterinary practice. Therefore, implementing a program of plaque control early in the pet’s life is extremely important because regular oral hygiene will not only improve gingival health, but may reduce the frequency of periodontal treatments. If oral hygiene care is begun at an early age, along with other routine grooming tasks such as ear cleaning and nail clipping, pets can learn to become more tolerant.

A variety of toothbrushes are designed for veterinary patients or a regular soft toothbrush in an appropriate size can be used. For reluctant patients, a clean damp washcloth is an alternative. Introduce brushing gently with a sulcular technique in the incisor area and work toward the molars on the buccal surfaces. As the patient becomes more accustomed to toothbrushing, it may be possible to include the lingual surfaces. Human toothpaste formulations should be avoided because they contain fluoride and foaming agents that may cause stomach upset in cats and dogs.18 Enzymatic toothpastes designed specifically for use on dogs and cats are available. They contain glucose oxidase and lactoperoxidase, which combine with water and oxygen in saliva to form hypothiocyanite, an ion that is produced naturally in canine and human saliva and has antibacterial activity.18 Clients can also encourage good oral health by choosing appropriate diets, toys, treats, and chews.

VETERINARY ORAL HEALTH COUNCIL

As dental awareness increases in the human population, clients are sure to transfer this concern to their pets. A huge market for pet products making claims of dental benefits has emerged and an evidence-based approach should be used when purchasing or recommending these products. In 1997 the Veterinary Oral Health Council (VOHC) was founded to recognize products that meet preset standards in reducing plaque and/or calculus. The VOHC does not test products itself but sets protocols for clinical studies. Manufacturers can voluntarily test their products and submit the results. Approved products must achieve at least a 10% reduction in plaque and/or calculus for products that use physical plaque control methods or a 20% reduction for products that include a chemical antiplaque agent. Products that successfully meet criteria for each submitted trial may display the “VOHC Accepted” seal.

PASSIVE HOME ORAL CARE

Most major veterinary diet manufacturers have formulated diets that make claims of dental benefits. There are two general mechanisms of action for dental diets. One is an enlarged kibble designed with textural and surface characteristics that mechanically inhibit the formation of plaque and calculus. This kibble design encourages chewing action and physically “scrubs” the teeth during mastication. The second design coats the outer surface of kibble with a polyphosphate, such as hexametaphosphate, to bind salivary calcium and inhibit calculus formation in the same way as human tartar control toothpaste. Some brands use both physical and chemical methods in the same formulation.18

Dogs that are active chewers have less plaque and calculus than dogs that are less active chewers.18 As a result, many toys, treats, chews, and rinses are available that make claims of dental benefits. Appropriate size, level of hardness and abrasiveness, and caloric content are factors to consider. A good rule of thumb is that if an imprint can be left in a toy or chew with your fingernail, it is probably the safest choice, especially for puppies and aggressive chewers. Some toys and chews are very hard and can contribute to tooth fractures in aggressive chewers. Also the coverings on traditional tennis balls are too abrasive. Specially designed nonabrasive tennis balls are available that are safe for dogs. A frequently updated list of VOHC-accepted products is available at www.vohc.org.

CONCLUSION

Studies show that fewer than 50% of clients are still compliant with pet oral care instructions after 6 months.19 The veterinary practitioner is charged with educating clients on the dental home care needs of their patients, overcoming preconceived ideas about the dental needs of veterinary patients, and with taking into account client values. Not a simple task! With knowledge of the obstacles faced in veterinary practices, human dental professionals can help their patients and themselves be advocates for the oral health of companion animals and good consumers of veterinary dental services.

REFERENCES

- Gorrel C. Veterinary Dentistry for the General Practitioner. 1st ed. Edinburgh: Saunders; 2004.

- Hennet P. Periodontal disease and oral microbiology. In: Crossley DA, Penman S, editors. Manual of Small Animal Dentistry. 2nd ed. Cheltenham: British Small Animal Veterinary Association; 1995:105-113.

- DeBowes LJ, Mosier D, Logan E, Harvey CE, Lowry S, Richardson DC. Association of periodontal disease and histologic lesions in multiple organs from 45 dogs. J Vet Dent. 1996;13:57-60.

- DeBowes LJ. The effects of dental disease on systemic disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1998;28:1057-1062.

- Hardham J, Dreier K, Wong J, Sfintescu C, Evans RT. Pigmented-anaerobic bacteria associated with canine periodontitis. Vet Microbiol. 2005;106:119-128.

- Harvey CE, Shofer FS, Laster L. Association of age and body weight with periodontal disease in North American dogs J Vet Dent. 1994; 11:94-105.

- Bezuidenhout AJ. Applied oral anatomy and histology. In: Slatter DH, ed. Textbook of Small Animal Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2003:2630-2637.

- Verstraete FJM, Kass PH, Terpak CH. Diagnostic value of full-mouth radiography in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1998;59:686-691.

- Verstraete FJM, Kass PH, Terpak CH. Diagnostic value of full-mouth radiography in cats. Am J Vet Res. 1998;59:692-695.

- Hale FA. Dental caries in the dog. J Vet Dent. 1998;15:79-83.

- Harvey CE. Feline dental resorptive lesions. Semin Vet Med Surg (Small Anim). 1993;8:187-196.

- Anderson JG. Diagnosis and management of gingivitis stomatitis complex in cats. Waltham Focus. 2004;13:4-7.

- American Veterinary Dental College. AVDC Veterinary Dentistry Directory. Available at: www.avdc-dms.org/dms/diplomates.cfm. Accessed October 12, 2009.

- Whitford GM, Biles ED, Birdsong-Whitford NL. A comparative study of fluoride pharmacokinetics in five species. J Dent Res. 1991;70:948-951.

- Robinson JG. Chlorhexidine gluconate—the solution for dental problems. J Vet Dent. 1995; 12:29-31.

- Hardham J, Reed M, Wong J, et al. Evaluation of a monovalent companion animal periodontal disease vaccine in an experimental mouse periodontitis model. Vaccine. 2005;23:3148-3156.

- Gengler WR, Kunkle BN, Romano D, Larsen D. Evaluation of a barrier dental sealant in dogs. J Vet Dent. 2005;22:157-159.

- Roudebush P, Logan E, Hale FA. Evidence-based veterinary dentistry: a systematic review of homecare for prevention of periodontal disease in dogs and cats. J Vet Dent. 2005;22:6-15.

- Miller BR, Harvey CE. Compliance with oral hygiene recommendations following periodontal treatment in client-owned dogs. J Vet Dent. 1994; 11:18-19.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2009; 7(11): 50-53.