Why Digital Intraoral Scanning Is the Future of Dentistry

Digital intraoral scanners enhance accuracy, efficiency, and patient comfort.

Gone are the days of hand-mixed materials — intraoral scanners have taken their place. Dental hygiene has expanded to include new forms of technology, including digital intraoral scanners, that impact the way clinicians practice.

Since their initial introduction, digital intraoral scanners have become much more user-friendly. The use of computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) began in 1973 with the introduction of optical impressions, now commonly known as digital impressions.1-3

Today, approximately 40% to 50% of dental offices use digital intraoral scanning, and this percentage is only expected to grow.1 Current systems include a scanner with the head created to fit within the oral cavity to capture files of the entire dentition. The files can be used to create restorations as well as appliances either within the dental office or via a lab. While digital intraoral scanning once focused solely on restorative needs, the opportunities for its use have expanded to applications in orthodontics and pathologies such as caries, erosion, and oral cancer. In modern dental practices, this technology can also be integrated into the dental hygiene appointment.1-4

Indications

Dental team members use digital scanning for a variety of reasons. Dentists utilize digital impressions to create crowns, veneers, inlays, onlays, occlusal guards, whitening trays, and to plan treatment for implants and orthodontics. Even though most of the scans are used by dentists, other team members help to acquire the digital scans. Dental assistants and dental hygienists may be asked to create scans.

Dental hygienists independently utilize digital scanning for education and motivation. Not only can the clinician educate the patient with the images, but the patient has a visual that is easily understood. These images contain powerful visuals of attrition, fractured teeth, abfraction, gingival recession, overjet, and crowding.4 Biofilm can be displayed after the application of disclosing solution.5 Separate photos are not required to capture the biofilm present when using digital scanning.

Benefits

Digital intraoral scanners may be preferred by the dental team and patients over physical impressions for several reasons. Their use eliminates the need to purchase additional supplies, such as impression material, spray adhesive, rope wax, trays, and stone. The chair time dedicated to impression taking is reduced because the clean up after the digital procedure is minimal.2 There is no need to disinfect, pour, and separate the impression from the tray.

Another advantage is ease of use. Obtaining a physical impression is more technique sensitive compared to using a digital intraoral scanner.6 Scanning requires the same skills as the intraoral camera. Many oral health professionals use an intraoral camera routinely, so learning the skill of scanning may be smoother than expected. If there is a need to scan the mouth, it will take only a minute or two.

Of the eight studies evaluated by Chandran et al,6 seven found that clinicians preferred digital impressions over physical impressions for reasons including time efficiency and difficulty level. Storing digital impressions electronically requires less physical storage space and makes them easier to find for future use; this complements the use of electronic records, which are becoming commonplace in dentistry.

Digital intraoral scans are more comfortable for the patient and provide superior accuracy.1,4,7,8 Digital impressions do not induce gagging and nausea, there is no taste associated with it, breathing is not impacted, and cold materials are not placed on sensitive tooth structures.6,7

The accuracy of the digital impression comes from the scanner’s ability to capture hundreds of images per minute that are stitched together to create a complete three-dimensional (3D) view of the oral cavity.1 The sharp focus found in 3D images ensures greater accuracy for a whitening tray, restoration, prosthesis, or appliance to fit properly. Chandran et al6 concluded that digital impressions are more likely to produce accurate impressions compared to physical impressions based on marginal fit and the fit of restorations. There is no contraction or expansion of digital impressions as can be found in physical impressions.

Patients may even be excited to take a digital impression knowing the practice is using new technology. Treatment timelines may be reduced as digital scans are sent electronically and arrive at the laboratory faster than physical impressions.9

Training

Training on the use of digital intraoral scanners is essential for their integration into dental practices. This begins with following manufacturer instructions for use as well as disinfection and sterilization.1 The accuracy of scanners is influenced by many factors, some patient-related and some of which fall under the responsibility of the clinician including choice of scanner, operator skill, regular technology calibration, and software maintenance.8,10

Accuracy is critical when creating whitening trays or occlusal guards that fit the dentition. A review of the literature by Alkadi8 demonstrated the importance of the clinician’s proficiency in which a more experienced clinician would achieve faster scans with more accuracy. Factors to consider with clinician proficiency include using a scanning distance of 10 mm to achieve the most accurate image and adhering to the manufacturer guidelines for scanning sequence. Software updates can affect the accuracy of the technology along with scanner head size, with a smaller tip creating lower accuracy.8 Slower scanning speeds and using a scanning pattern that begins on the occlusal surfaces may increase accuracy.8,11

There is a learning curve when new technology is introduced. Problems do occur while scanning. One is when the scanner stops capturing images and is essentially “lost” within the oral cavity due to inappropriate scanning speeds and patterns. This can be remedied by returning to an occlusal surface of the posterior teeth that has already been scanned by the device and restarting the scan.11

There is a learning curve when new technology is introduced. Problems do occur while scanning. One is when the scanner stops capturing images and is essentially “lost” within the oral cavity due to inappropriate scanning speeds and patterns. This can be remedied by returning to an occlusal surface of the posterior teeth that has already been scanned by the device and restarting the scan.11

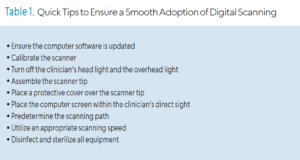

Table 1 provides some quick tips to follow as digital intraoral scanning is incorporated to provide a smoother transition in learning. While each manufacturer has specific instructions for use, these quick tips could be considered universal.

Obstacles

Digital scanners are revolutionizing dentistry, but some clinicians may continue using physical impressions. Cost can be a hurdle and learning new things takes time, but it’s an investment in the practice that benefits both patients and clinicians.11,12

The payoff includes more opportunities to educate the patient, but some clinicians may already feel maxed out on how many services they can offer during an appointment. Onboarding this equipment may require an adjustment to the appointment length to alleviate concerns from dental hygienists. The high price tag of this equipment may require sharing one scanner between the entire staff, which may slow down productivity related to its use. An additional concern for the operator may include the potential for eye strain from increased screen time.

“Technology is great when it works” is a common phrase and it rings true in the dental practice as well. Backup methods of capturing impressions are needed if the equipment fails to work properly. Utilizing the support services that come with the equipment is crucial to keep the workflow going when problems arise. Lastly, something to consider is maintaining the security of the electronic dental record after obtaining a digital impression. These images will become part of the electronic system incorporated throughout the practice or they could be stored exclusively on a computer connected to the scanner. Either way, the security of these images must be a priority for the office.

Conclusion

Regardless of the decision to adopt digital scanning or stick with the traditional method, it is clear that technology is here to stay. This renews curiosity and prevents stalemate from setting in while providing improved patient experiences. Many may be enticed to ditch the goo and embrace the new!

References

- Al-Hassiny A. Intraoral scanners: the key to dentistry’s digital revolution. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2023;44:154-156.

- Acker SR, Hartrick NE. Onboarding intraoral scanners and the digital workflow in your practice. Compend Educ Dent. 2023;44:590.

- Angelone F, Ponsiglione AM, Ricciardi C, Cesarelli G, Sansone M, Amato F. Diagnostic applications of intraoral scanners: A systematic review. J Imaging. 2023;9:134.

- Benvenuto VM, Sefo DL. The importance of the intraoral scanner. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2019;17(5):40-43.

- Giese-Kraft K, Jung K, Schlueter N, Vach K, Ganss C. Detecting and monitoring dental plaque levels with digital 2D and 3D imaging techniques. PLoS One. 2022 17:1-14.

- Chandran SK, Jaini JL, Babu AS, Mathew A, Keepanasseril A. Digital versus conventional impressions in dentistry: a systematic review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2019;13:1-6.

- de Paris Matos T, Wambier LM, Favoreta MW, et al. Patient-related outcomes of conventional impression making versus intraoral scanning for prosthetic rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prosthet Dent. 2023;130:19-27.

- Alkadi L. A comprehensive review of factors that influence the accuracy of intraoral scanners. Diagnostics. 2023;13:3291.

- Grauer D, Proffit WR. Accuracy in tooth positioning with a fully customized lingual orthodontic appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:433-443.

- Jung K, Giese-Kraft K, Fischer M, Schulze K, Schlueter N, Ganss C. Visualization of dental plaque with a 3D-intraoral-scanner – a tool for whole mouth planimetry. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0276686.

- Ural C, Kaleli N. Direct digitalization devices in today’s dental practice: Intra oral scanners. J Exp Clin Med. 2021;38:136-142.

- Al-Hassiny A, Végh D, Bányai D, et al. User experience of intraoral scanners in dentistry: transnational questionnaire study. Int Dent J. 2023;73:754-759.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July/August 2025;23(4):10-12.