MARK MILLER / SCIENCE SOURCE

MARK MILLER / SCIENCE SOURCE

Treating Patients With Myasthenia Gravis

Follow these strategies to provide safe and effective care to patients with this autoimmune disorder.

This course was published in the August 2013 issue and expires August 2016. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the clinical presentation of myasthenia gravis (MG).

- Identify oral manifestations common among patients with MG.

- Implement treatment modifications for patients with MG to ensure a safe and effective dental hygiene appointment.

- Discuss strategies for addressing a myasthenic crisis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

MG affects both genders and all races, and it can occur at any age, with an incidence rate of 20 per 100,000 people.1 Among adults age 20 to 50, women are more likely to be affected than men (3:2 ratio), with the highest incidence occurring between age 20 and 30. Men most often develop MG between age 50 and 60.2 Both sexes seem to be affected in equal numbers among adults over age 50.1–3 Many cases of MG remain undiagnosed because its symptoms resemble other autoimmune disorders and neurological conditions.

The incidence of MG is increasing, most likely due to better diagnostics, enhanced treatment protocols, lower mortality rates, and higher percentage of older adults in the population.3

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

In most cases of MG, the pathophysiology involves the formation of antibodies directed toward acetylcholine (ACh)—a neurotransmitter synthesized in motor nerve endings that is necessary for nerve impulse transmission to skeletal muscles. An autoimmune reaction causes these antibodies to interrupt connection between the nerve and muscle at the neuromuscular junction.4 Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) are docking areas for ACh (Figure 1). The antibody attack causes complement-mediated destruction of muscle cell receptor sites—blocking nerve impulse conduction along the pathway at normal conduction speeds.5,6 Due to a lack of ACh, normal impulse transmission is blocked because receptors at the myoneural junction cannot depolarize and effectively induce muscle contraction.7,8 This causes the muscle weakness characteristic of MG.

The thymus gland, which plays a critical role in the developing immune system, is also involved in the pathogenesis of MG. A majority of patients with MG have altered gland function, and 75% have a thymona—a tumor of the thymus gland or thymic hyperplasia.9,10 The association between the thymus gland and MG is unclear, and it is not known whether thymic changes play a primary or secondary role in disease pathogenicity.9 The thymus may cause the autoimmune dysfunction through an overproduction or prolonged synthesis of thymic hormones, resulting in autoimmunity and production of AChR antibodies.10

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical course of MG varies substantially, but it is generally progressive and results in weakness of striated voluntary muscles. The muscles involved vary and the degree of severity ranges from mild to severe. Periods of remission and relapse are common.6–8 Most individuals experience weakness in the upper extremities. Many factors can exacerbate MG symptoms, including: infection, increased body temperatures, exercise, pregnancy, emotional stress, hormonal changes, and medications that affect neuromuscular transmission.6–9 Individuals with MG typically feel best in the morning, with the feeling of fatigue progressing as the day wears on; however, signs can vary from hour to hour. Regardless of the time of day, prolonged exertion causes muscle fatigue and weakness in patients with MG.

A gradual onset of symptoms is common, and muscle weakness is differentiated into three categories: ocular, bulbar, and trunk/limb. The muscles of the eyes and oropharyngeal area are most frequently impacted during the beginning stages of the disorder.7,9 The weakness often becomes more generalized, spreading to other muscles innervated by the cranial nerves—including those that control breathing and limb movement.6,7 Movement of the eye and eyelids is initially affected with the levator palpebrae, orbicularis oculi, and extraocular muscles becoming involved.2,6–9 The medial rectus muscles, which turn the eyeballs, are the most severely affected. As a result, varying degrees of ocular weakness manifest, such as droopy eyelids or ptosis (Figure 2), constant or transient double vision, and nystagmus (reduced vision). Asymmetrical ptosis is a hallmark of MG and can be unilateral or bilateral.11 Onset of ocular symptoms is often slow; therefore, many individuals may experience symptoms for years before receiving a diagnosis of MG.4

ORAL MANIFESTATIONS

More than 50% of patients diagnosed with MG have bulbar muscle involvement (mouth and throat muscles), and 19% present with oropharyngeal symptoms.8 With bulbar involvement, muscle weakness causes problems with swallowing, choking, facial movement, holding up the head, and articulation. Due to lack of strength in the muscles of mastication, the ability to eat becomes challenging.11,12 Weight loss, dehydration, and malnourishment may result.11

Facial movement is limited, resulting in an expressionless face.11 Chronic contraction of the frontalis muscle causes a worried or surprised look, and one eyebrow may be raised higher than the other. Because of weakness in the muscles that control the upward curl of the mouth, patients may not be able to smile; rather a snarling or flattened appearance occurs, with the corner of the mouth drooping.5,6 Due to masseter muscle weakness that prevents the mandible from closing, some individuals cannot close their mouths. Palatal and pharyngeal muscle involvement can cause slurring, stuttering, alteration of voice tone, and dysarthria.11 Myasthenic speech is characteristically nasal sounding, due to weakness of the soft palate and impaired lip movement. Dysarthria results from lack of control and execution over speech muscles.4,11 Hypophonia occurs as the laryngeal muscles are affected, with voice changes ranging from breathiness and softness to hoarseness.

GENERALIZED MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

In most people with MG, muscle weakness becomes widespread, moving from ocular and oropharyngeal muscles to the trunk and extremities, resulting in a generalized form of MG. The triceps are often affected, first with patients experiencing problems raising their arms over their heads and rising from a sitting position. Due to specific weakness in wrist and finger extensors, performing fine motor tasks, such as writing or performing oral self-care, may become problematic.2 Neck flexors, deltoids, hip flexors, and finger/wrist extensors are the muscles most commonly affected among patients with generalized MG. Neck flexors are affected more often than neck extenders.6

Respiratory muscle weakness is a potentially life-threatening condition experienced by those with MG.6–10 Approximately 20% to 40% of people with MG exhibit weakness of the intercostal muscles and the diaphragm, which can cause a myasthenic crisis—an acute exacerbation of symptoms with respiratory arrest.12 Shortness of breath and an inability to swallow, cough, and clear secretions often lead to respiratory distress, which requires intubation and ventilator support.8 A myasthenic crisis may be precipitated by a negative reaction to a medication, surgery, stress, fever, or infection.

TREATMENT

Treatment goals for patients with MG focus on both controlling muscle weakness and prolonging periods of remission. In general, the use of cholinesterase (CHE) inhibitors is the therapy of choice.13 These drugs improve muscle function by inhibiting breakdown of ACh, so it can accumulate at the neuromuscular junction. Pyridostigmine bromide (Mestinon®) is the CHE inhibitor most commonly prescribed for MG.13 Optimal dosage varies, but improvements can be seen within 40 minutes of ingestion, with the effects lasting up to 4 hours. Taking the correct dose is imperative, as toxic amounts of CHE inhibitors may cause a cholinergic crisis, resulting in muscle weakness and possible respiratory collapse.14

If patients with MG do not respond well to CHE inhibitors, corticosteroids may be added to the drug regimen. Steroids may inhibit antibody formation, with prednisone being the corticosteroid of choice. Azathioprine and cyclosporine are additional immunosuppressive medications prescribed to diminish the abnormal action of the immune stimulus related to antibody production.1 However, benefits must be closely weighed against side effects (such as prolonged wound healing and increased risk of infection). Surgical removal of the thymus gland improves symptoms in some individuals, but the response is unpredictable.10 Surgical thymectomy is limited to medically stable adults with generalized MG and those with a thymoma.

When patients with MG are in an acute situation, such as a myasthenic crisis, plasma exchange is a recommended short-term therapy. With plasmapheresis, ACh antibodies that contribute to the autoimmune condition are removed from the circulating plasma.15 Positive effects are quick, last up to 3 months, and may be useful until other medications become effective.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR DENTAL HYGIENE CARE

Oral health professionals need to communicate with the patient’s physician before treatment begins to ensure that it is safe to provide dental care. Patients with uncontrolled MG or significant oropharyngeal or respiratory weakness should receive treatment in a hospital-based dental setting.16 Control of oral infection is critical because any presence of infection will exacerbate MG.14

To ensure a safe, efficient, and effective appointment, several adaptations in dental hygiene care planning are warranted. Appointments should be scheduled during the time of day when the patient feels the best. For most patients, muscle weakness is less pronounced in the morning (when ACh levels are highest), and gets worse throughout the day.16 Patients should also take their CHE inhibitor medication 1 hour to 11/2 hours before their dental appointment to ensure that the medication reaches maximum efficacy immediately before treatment.14,17 This is when neck and facial muscles have their greatest strength, facilitating a more efficient and effective visit. To conserve patient energy, a handicapped parking space should be made available. Upon arrival, the patient should be allowed to rest in a cool environment to regain strength.18 Treatment should be provided in an operatory close to the reception area to reduce the patient’s exertion level.

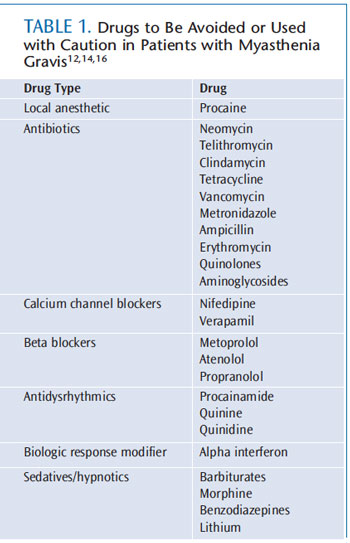

Patients with MG need brief appointments. To promote efficiency during the dental visit, patients should be asked to complete medical history forms prior to arrival and a hygiene assistant should be used during the appointment. In addition, temperatures in the treatment areas should be kept cool, as heat may exacerbate symptoms.11 Prior to treatment, a thorough review of the patient’s medication regimen is critical in order to prevent adverse reactions during dental hygiene care. Patients taking CHE inhibitors may experience potential complications with other medications used in dentistry, creating a health crisis (Table 1).12,14,16 When patients need pain control for periodontal debridement, estertype anesthetics—such as procaine—should be avoided. Ester agents are metabolized more slowly due to hydrolysis by plasma cholinesterase, which increases the risk of a toxic reaction.11 An amide local anesthetic, such as lidocaine or mepivacaine, is recommended.

Bilateral blocks should be avoided due to swallowing problems. A vasoconstrictor should be used with local anesthesia to increase efficacy at the oral site and minimize overall dosage.14 The patient’s physician should be consulted before antibiotics are prescribed because some types may exacerbate muscle weakness. In general, aminoglycosides, bacitracin, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, and neomycin should be avoided (Table 1).12,14,16 Penicillin does not cause neuromuscular blocking and can be safely prescribed.14,16 Because stress may cause disease exacerbation, a relaxed appointment is imperative.19 Developing a relationship with the patient, in addition to effective pain management, will help manage stress.14

Additionally, soothing music, elimination of extraneous noises, aromatherapy, and anticipatory guidance may promote relaxation and minimize anxiety during dental hygiene care.19 Nitrous oxide-oxygen sedation may also be safely used to manage anxiety and stress.11 Sedatives, such as benzodiazepines and barbiturates, should be used with caution, especially in patients with respiratory issues.11 For patients experiencing articulation problems, the presence of a caregiver in the treatment area may reduce anxiety and help facilitate verbal communication.19

Patients with MG are at high risk of pulmonary aspiration, due to their weakened oropharyngeal musculature, which causes problems with sealing of the laryngeal inlet.14 Therefore, power scalers and air polishers are contraindicated. Use of high-speed suction is imperative to prevent oral debris from being aspirated.16,19 Patients with weakened head and neck muscles may prefer a semi-upright position to minimize choking, pooling of saliva, and to avoid closing of the throat. Using a mouth prop can lessen muscle strain in patients who have difficulty keeping their mouths open.19 The tongue may be furrowed with a flaccid appearance. The lack of muscle tone may also result in a loss of contour. Patients may have problems with retaining dentures because of muscle control. Encourage patients to alert the oral health professional when they need a break.

Because patients with MG often have problems, shining a dental light in their eyes should be avoided as much as possible. The use of dark lenses may reduce eye strain. Protective lenses are also important, as most MG patients have weak eyelid closure. The eyes may appear closed initially, but over time, gaps can appear between the lids.

Several medications used to manage the symptoms of MG have side effects that may alter dental hygiene care. Drug-influenced gingival enlargement is a potential problem in patients who are taking cyclosporine, and may begin within the first month of drug use.16 Educating patients about the importance of excellent oral self-care to minimize this potential side effect is critical. Antibiotic premedication may be necessary for patients taking corticosteroids, cyclosporine, or azathioprine, due to immune suppression and the potential for increased oral and fungal infection. Due to delayed wound healing, a slower recovery from periodontal debridement may be expected.16

ADDRESSING A MYASTHENIC CRISIS

Dental hygienists must be knowledgeable about the symptoms of a myasthenic crisis, which occurs when the muscles that regulate breathing weaken, leading to inadequate ventilation. Myasthenic crisis constitutes a medical emergency. A complaint of breathing difficulty must be taken seriously. Symptoms that may seem minor can quickly escalate to a life-threatening respiratory condition. Patients may experience rapid, shallow breathing and anxiety, due to their inability to draw a full breath.

Dental hygienists must be prepared to maintain an open airway, perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and call for emergency assistance if respiratory collapse occurs. High-speed suction may be helpful to prevent aspiration of secretions and debris and blockage of the airway before emergency services arrive.16

ORAL SELF-CARE

In order to provide compassionate and quality care, dental hygienists must maintain realistic expectations about what patients with MG can accomplish and provide encouragement.19 Oral musculature dysfunction, coupled with a weakened grasp and wrist and finger extensors, create challenges when performing oral self-care.19 As is the case with many patients who have chronic health conditions, disease status often influences how well oral self-care is practiced.

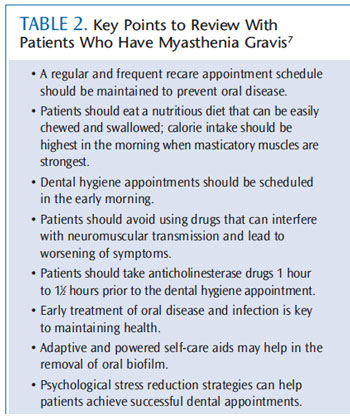

When MG is exacerbated, patients’ oral self-care is compromised due to fatigue levels and hand muscle weakness. To control oral infection, frequent recare appointments should be encouraged, with the interval time shortened from 3 months to 2 months when self-care ability is compromised for an extended period. Table 2 lists important points to discuss with patients.7

Self-care instruction is critical because oral infection can cause a myasthenic crisis. Therefore, each self-care regimen must be customized to the patient. For patients experiencing dexterity issues, powered toothbrushes and flossing devices may facilitate effective self-care practices and conserve energy. However, the extra weight associated with a powered oral hygiene device may make its use too difficult for patients with wrist and hand weakness. Alternative manual toothbrush heads, designed to surround the entire tooth to remove biofilm from the facial, lingual, and occlusal surfaces simultaneously—reducing the number of brushing strokes required—may be beneficial. However, the bristles on these brush heads do not reach more than a few millimeters into the gingival margin and may not provide a thorough cleaning for patients with significant recession. For some, extending or enlarging the toothbrush handle may prove helpful. Patients with involvement may need written materials created in large, dark print to facilitate readability of take-home information. Keeping an in-office optical magnifier will assist patients with reading written materials during the appointment.18

CONCLUSION

MG is mediated through autoantibodies against the AChR complex, and is characterized by fluctuating muscle weakness, often in the oropharyngeal area. Impairment of the neuromuscular junction causes defects in the nerve impulse transmission, resulting in weakness of the voluntary muscles. Dental hygienists must be prepared to make several adjustments when working with patients affected by MG in order to ensure a safe and effective dental appointment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

FIGURE 1. JAMES KING-HOLMES/SCIENCE SOURCE

FIGURE 2. DR M.A. ANSARY/SCIENCE SOURCE

REFERENCES

- National Institute of Neurological Disordersand Stroke. Myasthenia Gravis Fact Sheet.Available at: www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/myasthenia_gravis/detail_myasthenia_gravis.htm. Accessed July 15, 2013.

- McGrogan A, Sneddon S, de Vries C. Theincidence of myasthenia gravis. systemic iterature review. Neuro epidemiology.2010;34:171?183.

- Meriggioli MN, Sanders DB. Auto immunemyasthenia gravis: emerging clinical and biological heterogeneity. Lancet Neuro.2009;8:475–490.

- Angelini C. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Clin Drug Investig. 2011;31:1?14.

- Scherer K, Bedlack RS, Simel DL. Does thispatient have myasthenia gravis? JAMA.2005;293:1906?1914.

- Jayam Trouth A, Dabi A, Solieman N,Kurukumbi M, Kalyanam J. Myasthenia gravis:a review. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:874680.

- Armstrong SM, Schumann L. Myastheniagravis: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2003;15:72?78.

- Abbott S. Diagnostic challenge: myastheniagravis in the emergency department. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2010;22:468?473.

- Raica M, Cimpean AM, Ribatti D. Myastheniagravis and the thymus gland: a historical review. Clin Exp Med. 2008;8:61?64.

- Tormoehlen LM, Pascuzzi RM. Thymoma,myasthenia gravis, and other paraneoplastic syndromes. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am.2008;22:509?526.

- Patil PM, Singh G, Patil SP. Dentistry andthe myasthenia gravis patient: a review of the current state of the art. Oral Surg Oral MedOral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:e1?8.

- Rai B. Myasthenia gravis: challenge todental profession. The Internet Journal ofAcademic Physician Assistants. 2007;6(1):18?20.

- Treat myasthenia gravis with individualized doses of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and immunomodulators. Drugs & TherapyPerspectives. 2011;27(7):18?21.

- Yarom N, Barnea E, Nissan J, Gorsky M.Dental management of patients with myasthenia gravis: a literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med OralPathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:158?163.

- Mao ZF, Mo XA, Qin C, Lai YR, Hartman TC.Course and prognosis of myasthenia gravis: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:913?921.

- Jamal BT, Herb K. Perioperative management of patients with myasthenia gravis: prevention, recognition, and treatment.Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:612?615.

- Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America Inc.Dental treatment considerations. Available at:www.myasthenia.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=I5LnDa2XVs8%3D. Accessed July 15, 2013.

- Job Accommodation Network.Accommodating and compliance series:employees with myasthenia gravis. Available at:askjan.org/media/downloads/MGA&CSeries.pdf.Accessed July 14, 2013.

- Tolle SL. Myasthenia gravis: a review fordental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2007;81:1?9.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2013; 11(8): 14-18.