KATARZYNABIALASIEWICZ/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

KATARZYNABIALASIEWICZ/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Treating Patients with Anxiety Disorders

Proper preparation will help clinicians effectively care for this population, improving the likelihood that patients will return for regular oral health care.

This course was published in the April 2018 issue and expires January 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the different types of anxiety disorders and their treatment.

- Discuss the oral health implications of anxiety disorders and their treatment.

- Describe strategies for effectively treating patients with anxiety disorders.

Pathologic anxiety disorders present when anxious responses are excessive, uncontrollable, lack a stimulus, and result in behavioral and cognitive changes.5,6 Stress, systemic illness, psychiatric disorders, genetics, environment, and a combination of psychological and biologic processes may be the cause.3,4,7,8 Patients with anxiety disorders are likely to present in the dental office and oral health professionals need to be adequately prepared to provide treatment in a safe and effective manner.

TYPES OF ANXIETY DISORDERS

The four most common anxiety disorders are: panic disorder; obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD); post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); and phobias, such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and social anxiety disorder (SAD).3,7,9

Panic disorder results in sudden feelings of fear leading to panic attacks.7,9 Individuals experiencing a panic attack might exhibit symptoms such as chest pain, heart palpitations, shortness of breath, dizziness, upset stomach, feelings of disconnect, and fear of death.7,9Panic disorders can create feelings of shame, self-consciousness, and fear of another attack.7–9 When patients fail to seek treatment early, panic disorders may cause them to avoid places where attacks have occurred.6–8

Individuals with OCD experience obsessions and compulsions that seem impossible to control.9–11 If their compulsions are not performed numerous times a day in a specific way, individuals with OCD experience anxiety that often interferes with daily life.9–12

PTSD is a feeling of distress brought on by the experience of a traumatic event.6,9,13 When faced with situations that are threatening or can cause harm, the fight-or-flight response is triggered in healthy individuals.14 In contrast, those with PTSD experience the activation of this reaction in the absence of danger.14 Symptoms of PTSD are divided into three categories: re-experiencing, avoidance, or hyperarousal symptoms.14 Re-experiencing symptoms include nightmares, flashbacks, and/or frightening thoughts.6,13,14 Avoidance symptoms involve isolation from places, events, or objects that remind the individual of the traumatic experience.6,13,14 In addition, feelings of numbness, guilt, depression, worry, loss of interest in activities once enjoyed, and difficulty remembering the traumatic event are common.9,13,14 Becoming easily startled or scared, feeling tense and angry, and/or difficulty sleeping are symptoms of hyperarousal.6,9,13,14

Phobias are characterized by irrational fear.9 Individuals with GAD have severe, chronic, and inflated worry about events in daily life.7–9,15 Although most individuals realize their reactions are not proportionate to the situation, they are unable to control their anxiety.8 GAD may result in insomnia, difficulty concentrating, being easily startled, fatigue, headaches, muscle tension/aches, difficulty swallowing, trembling, twitching, irritability, sweating, nausea, lightheadedness, frequent urination, hot flashes, and breathlessness.7,8 SAD manifests in fear of public humiliation with symptoms such as feeling self-conscious, embarrassed around others, and worry before events, as well as difficulty communicating, nausea, trembling, sweating, and blushing.7–9

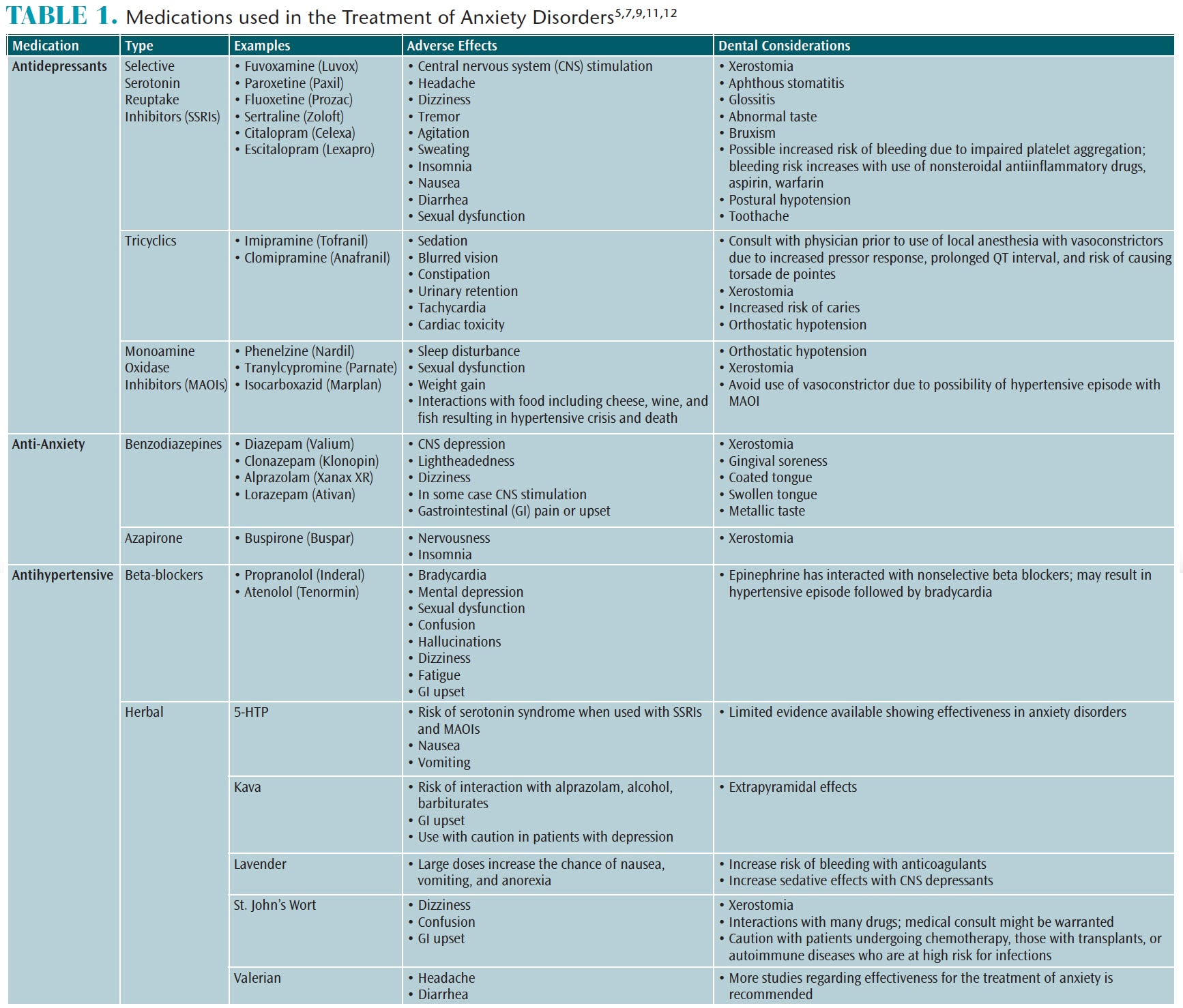

The treatment of anxiety disorders includes psychological, behavioral, and pharmacological modalities.5,8,9 While they do not provide a cure, medications can be effective in controlling symptoms.8 The most common medications are antidepressants, anti-anxiety drugs, and beta-blockers.8,9,16

Table 1 (page 50) provides a list of the medications and herbal supplements commonly used to treat anxiety disorders, their adverse reactions, and associated dental considerations. Patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), or benzodiazepines are at risk for xerostomia, increasing caries risk.17,18 These medications may also interact with dental anesthetics. A medical consultation may be prudent for patients taking TCAs when the use of a vasoconstrictor is warranted, due to an increased pressor response, prolonged QT interval, and the risk of torsade de pointes.17,18 Furthermore, vasoconstrictors should be avoided in patients taking MAOIs due to an increased risk of hypertension, gastrointestinal upset, headache, dizziness, insomnia, central nervous system stimulation, and tremors.17,18 Opioids should not be prescribed without a medical consultation, as some of these medications may intensify the opioid’s effects.

Herbal supplements are often used by patients to control anxiety. Patients may be self-prescribing these supplements and there may be interactions with prescribed medications for other systemic conditions or medications used in the dental office.

ORAL HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

Patients with anxiety disorders are more likely to have unmet dental needs, are less likely to visit the dental office regularly, and tend to ignore oral conditions.19–22 Also, they are more likely to seek care in a hospital emergency department due to pain caused by dental caries, periodontal lesions, periapical lesions, and/or oral cellulitis.21 Poor oral health among patients with anxiety disorders is linked to lifestyle choices and the effects of medications used to treat their conditions.20,22 Patients with anxiety disorders may be more susceptible to caries, untreated restorative needs, stomatitis, glossitis, gingivitis, gingival recession, abrasion, periodontal diseases, medication-related xerostomia, soft tissue lesions, temporomandibular joint disorder, and increased levels of biofilm and calculus.16,19–21,23

CARE CONSIDERATIONS

Oral health professionals need to approach patients experiencing anxiety disorders with a supportive, nonjudgmental attitude.16,24,25Clinicians should verify patients’ medication usage to avoid drug interactions and to note any oral symptoms.18 SSRIs inhibit isoenzymes that metabolize codeine, erythromycin, and carbamazepine.16 Antihistamines, muscle relaxants, and opioid analgesics heighten the tranquilizing effects of benzodiazepines.16 Additionally, hydrocodone may induce symptoms of a panic attack.

The use of caries management by risk assessment (CAMBRA) is appropriate when treating patients with anxiety disorders. When a patient presents with a moderate to high caries risk, the dental team should adhere to the American Dental Association’s (ADA) clinical recommendations for radiographs and fluoride treatments. These state that children and adolescents at increased caries risk should have posterior bitewing exams at 6-month to 12-month intervals and adults at 6-month to 18-month intervals.26 Patients at an increased risk of caries should receive 2.26% professional fluoride varnish applications every 3 months to 6 months.27 Additionally, the ADA recommends that high caries risk patients use a 0.09% fluoride rinse weekly or a 0.5% fluoride gel or paste twice daily.27

Considering the increased risk for periodontal diseases and caries, patients with anxiety disorders need to receive thorough oral hygiene instructions.16,20,28 Oral education aids, such as brochures, pictures, models, and software programs can be helpful tools.28Artificial salivary products should be considered to reduce the effects of medication-induced xerostomia.16,20

When local anesthesia is indicated, special precautions should be taken.16 Anesthetic selection should be based on the type of procedure, duration of anesthesia required, length of time of the procedure, and needs and/or preferences of the patient.24 As an alternative to local anesthesia, topical sprays, rinses, or subgingival gels may be used.24 Nitrous oxide sedation might also be a useful adjunct.24 For more severe cases of anxiety or in the event of extensive dental needs, intravenous conscious sedation might be indicated.24,25

In order to facilitate the comfort of patients with anxiety disorders, the dental team should help them feel in control of their appointments.24 Brief appointments scheduled early in the morning are helpful.28 Allowing patients to take breaks and sit up when needed provides opportunities to relax during procedures.16,24,25 Positive reinforcement can strengthen patients’ morale and encourage them to return.25 Oral health professionals should use open communication to address patients’ values and concerns about their treatment in order to achieve and maintain oral and overall health.24,25,28 Motivational interviewing might be helpful in uncovering patients’ resistance to oral health behavior modification and provide the impetus needed to make positive changes.28

Implementing stress-reduction strategies, such as deep breathing and focusing on a certain spot, may help reduce patient anxiety.24,25,28 Oral health professionals can suggest that patients visualize themselves in a scene using all five senses or listen to music throughout the appointment.25,28 Clinicians should use a calm voice and be conversational.24,25 In addition, tools such as noise-cancelling headphones, pillows, blankets, or neck wraps may be helpful. Aromatherapy with essential oils has been shown to reduce moderate anxiety due to its ability to reduce salivary and serum cortisol, increase blood flow, and decrease systolic blood pressure.25 Patients should be encouraged to share the stress-reduction protocols that work best for them.

MEDICAL EMERGENCIES

The risk of medical emergencies may be elevated when treating this patient population and oral health professionals should be prepared. Careful taking of patients’ health histories can help clinicians anticipate a medical emergency.29 Vital signs should be recorded for all patients, as they could provide early indication a patient is experiencing anxiety. Past dental experiences, sights, sounds, and smells may induce a panic attack in patients with anxiety disorders.25,28 If a patient begins to exhibit the signs and symptoms of a panic attack, treatment should cease until the patient has calmed down and is ready to proceed. Early recognition of these signs might allow the clinician to reassure the patient so that treatment may be completed.28 If a patient is unable to continue with treatment, emergency medical services or the assistance of a family member—especially to provide a way home for the patient—may be necessary. Calling the patient that evening to check on him or her is a helpful gesture that my encourage the patient to return to complete treatment.

In the case of a more severe panic attack, syncope, or fainting may occur. Oral health professionals should initiate medical emergency management by taking vital signs and checking airway, breathing, and circulation.29 The patient should be placed in the supine position and should regain consciousness within 1 minute.29

REFERENCES

- National Institute of Mental Health. Any Anxiety Disorder. Available at: nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/any-anxiety-disorder-among-adults.shtml. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Post by Former NIMH Director Thomas Insel: Mental Health Awareness Month: By the Numbers. Available at: nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2015/mental-health-awareness-month-by-the-numbers.shtml. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Facts and Statistics. Available at: adaa.org/about-adaa/press-room/facts-statistics. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- de Lijster JM, Dierckx B, Utens EMWJ, et al. The age of onset of anxiety disorder: a meta-analysis. Can Psychiatr Assoc J. 2017;62:237–246.

- Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL. Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. 9th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2013:544–560.

- Little JW. Anxiety disorders: dental implications. Gen Dent. 2002;51:562–568.

- Medscape. Anxiety Disorders. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/286227-overview. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Anxiety Disorders. Available at: nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders/index.shtml. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. Anxiety Disorders. Available at: nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Anxiety-Disorders. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Understand the Facts: Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Available at: adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd. Accessed on March 19, 2018.

- Mayo Clinic. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Available at: mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/obsessive-compulsive-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20354432. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Available at: nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd/index.shtml. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Understand the Facts: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Available at: adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/symptoms. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Available at: nimh. nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/index.shtml. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Understanding the Facts: Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Available at: adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/generalized-anxiety-disorder-gad. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- Friedlander AH, Marder MD, Sung EC, Child JS. Panic disorder: psychopathology, medical management, and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:771–778.

- Wynn, RL, Meiller, TF, Crossley, HL. Drug Information Handbook for Dentistry. 23rd ed. Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp Inc; 2017.

- Haveles EB. Applied Pharmacology for the Dental Hygienist. 7th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2015.

- Heaton LJ, Mancl LA, Grembowski D, Armfield JM, Milgrom P. Unmet dental needs in community-dwelling adults with mental illness: Results from the 2007 medical expenditure panel survey. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:16–23.

- Kisley S. No mental health without oral health. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:277–282.

- Nalliah RP, Da Silva JD, Allareddy V. The characteristics of hospital emergency department visits made by people with mental health conditions who had dental problems. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:617–624.

- Edward KL, Felstead B, Mahoney AM. Hospitalized mental health patients and oral health. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2012;19:419–425.

- Gatchel RJ, Garofalo JP, Ellis E, Holt C. Major psychological disorders in acute and chronic TMD: An initial examination. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:1365–1370.

- Byrd E. Strategies for dental hygienists who treat patients with dental anxiety or phobia. Available at: dentistryiq.com/articles/2016/10/strategies-for-hygienists-who-treat-patients-with-dental-anxiety-or-phobia.html. Accessed March 19, 1018.

- Appukuttan DP. Strategies to manage patients with dental anxiety and dental phobia: A literature review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2016;8:35–50.

- American Dental Association. Dental radiographic examinations: recommendations for patient selection and limiting radiation exposure. Available at: ada.org/~/media/ADA/…/FIles/Dental_Radiographic_Examinations_2012.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2018.

- Weyant, RJ, Tracy, SL, Anselmo, T, et al. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: Executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1279–1291.

- Sefo DL, Stefanou L. Quelling dental anxiety. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2014;12:70–73.

- Reed, K.L. Basic management of medical emergencies: Recognizing a patient’s distress. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(Suppl 1):20–24.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2018;16(4):48-51.