Tips on Managing Childhood Caries

Fluoride-based strategies are essential in preventing and addressing tooth decay, with recommendations tailored to each child’s individual risk assessment.

This course was published in the September/October 2025 issue and expires September 2028. This two-unit CE course is supported through an unrestricted educational grant from Colgate. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 440

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the role of caries risk assessment in prevention and management of tooth decay.

- Differentiate between primary, secondary, and tertiary caries prevention.

- Explain the safety profile of topical fluoride.

A Risk-Based Approach to Caries Prevention

Introduction

In recent years, a powerful shift in the understanding of caries management has taken oral health professionals by storm. Caries is a chronic infectious disease closely linked, not only to overall oral health but also, interestingly, to systemic health. This understanding is transforming how we approach patient care, leading to improved outcomes, a higher standard of treatment, and better long-term prognoses.

This change in perspective on caries (and also periodontal diseases) has turned caries risk assessment into a critical element of treatment — more important than merely a reference for preventive measures. The evaluation of risk factors, as part of a bigger picture, gives the opportunity to intervene beyond restorative treatment.

Unfortunately, this approach is not as easy as filling out a risk assessment form, but rather requires our full knowledge and attention in order to offer the best for our patients. This article offers a review of caries risk assessment and, more important, the different levels of prevention that can sometimes be overlooked.

— Martin Pendola, PhD

Scientific Affairs Manager

Colgate Oral Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Tips for Managing Childhood Caries

While the overall oral health of Americans has steadily improved since the 1960s, significant gaps in pediatric dental care remain. In 2020, the United States Department of Health and Human Services reported that most children still lacked access to adequate dental care.1 According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), preventive measures, such as drinking fluoridated water, using topical fluorides, and sealant application on permanent teeth, are effective at reducing the risk of childhood caries.2 However, many children continue to go without these benefits and do not have a regular dental provider (dental home), highlighting the need for expanded access and education.

To address such disparities among children, Adeghe3 suggests that oral healthcare be incorporated into primary care settings. Within such interdisciplinary teams, children would receive a caries risk assessment at all preventive visits, regardless of whether the setting is medical or dental.

Caries risk assessments support clinicians in making individualized recommendations based on patient needs. These recommendations should include personalized guidance of oral self-care products such as over-the-counter fluoride dentifrice, over-the-counter fluoride mouthrinse, prescription fluoride dentifrice, and professionally applied topical fluorides.

As communities across the country debate the use of preventive measures, such as community water fluoridation, to prevent caries, oral health professionals should be prepared to identify how best to provide preventive education and health promotion.

Assessing Risk of Tooth Decay

Individualized treatment plans should include tailored oral self-care recommendations and fluoride products based on risk assessment.4 Children should have caries risk assessed via a caries risk assessment form, which highlight the variables associated with an increased caries risk such as family brushing habits, little to no fluoride exposure, previous caries experience and nutritional habits.5

The American Dental Association (ADA)6 offers two separate caries risk assessment forms: one for patients between the ages of 0 and 6 and the other for those older than age 6. The forms inquire about contributing health issues, general health status, and clinical conditions that impact caries risk. Contributing conditions include fluoride exposure types, such as toothpaste, fluoridated drinking water, professionally applied fluorides, and supplements.7 For those with exposure to fluoride, the clinician marks “yes” under the low caries risk column. For those without exposure to these forms of fluoride, the clinician marks “no” under the moderate risk column.

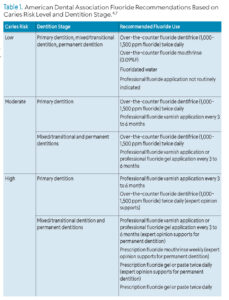

Other caries risk assessment forms consider a variety of factors. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry’s (AAPD) caries risk assessment form lists protective factors as daily toothbrushing with fluoride toothpaste, optimally fluoridated water, professionally applied topical fluoride, and regular dental care. The AAPD recommends that children ages 6 and older at high caries risk use prescription dentifrice when toothbrushing.8 Regardless of which caries risk tool is used, clinicians should base their at-home and professional fluoride recommendations on the patient’s caries risk level (Table 1).4,6

Risk Assessment as the Foundation of Fluoride Recommendations

Children ages 0 to 5 and 6 and older who are at low risk for caries should use over-the-counter fluoride dentifrice twice daily during toothbrushing.4 Over-the-counter fluoride dentifrices typically contain at least 1,000 ppm and less than 1,500 ppm fluoride.5 Pediatric patients at low risk for dental caries may not need additional fluoride recommendations.

Children at moderate to high risk of caries should have professional topical fluoride treatments — either 5% sodium fluoride varnish at 22,600 ppm or 1.23% acidulated phosphate fluoride gel delivered in a tray for 4 minutes — every 3 to 6 months.4 For children ages 6 and older at high risk of caries, prescription 0.5% (1.1% sodium fluoride or 5,000 ppm) fluoride dentifrice should be used twice daily during toothbrushing.4

Primary Prevention

With Utah and Florida banning fluoride in the public water supplies and other states possibly following, caries prevention is of the utmost importance. Caries remains the most common chronic childhood disease.9 Left unmanaged, weakened tooth structure becomes demineralized and eventually cavitated. Then, the carious lesion progresses until treatment is the only option to maintain the dentition. If primary teeth are lost too early, there may be implications for the permanent dentition, and then the effects of childhood caries may follow the individual into adulthood.8

Primary prevention includes preventive measures and treatments delivered before dental disease is present. From when the teeth first erupt, primary preventive measures should be followed. Permanent teeth begin to erupt at around age 6. The first permanent molars are not only difficult for children to access with a toothbrush, but the occlusal anatomy increases the risk of decay due to the irregularities of developmental grooves and pits. The most effective means of primary prevention of dental caries is through the use of fluoride.10

Oral self-care procedures, with the help of an adult, are imperative in the early stages of tooth eruption. Children should be encouraged to use their toothbrush with fluoride toothpaste and then have an adult check their brushing with follow-up brushing afterward.5,11 Over-the-counter fluoride toothpastes should have the ADA’s Seal of Acceptance. The fluoride content of over-the-counter dentifrice is at least 1,000 ppm fluoride and less than 1,500 ppm fluoride. All children, regardless of caries risk, benefit from using an over-the-counter fluoride dentifrice twice daily.5

Mouthrinse is another over-the-counter topical fluoride product that may be used at home. Fluoride mouthrinses should not be recommended until age 6, to ensure that the child can adequately expectorate in order to prevent accidental ingestion of topical fluoride.5 Recommendations for over-the-counter fluoride mouthrinses should include products with the ADA Seal of Acceptance.

Professional fluoride treatments are also recommended as a primary preventive measure, especially for children at high caries risk.5 Fluoride varnish contains 22,600 ppm fluoride. The varnish is an excellent topical fluoride because it has substantivity, or staying power. Fluoride is released into the enamel for 24 to 48 hours after application. Additionally, the varnish stays on the tooth upon application as it hardens, or sets, when in the presence of saliva. This minimizes consumption of fluoride varnish. Sodium fluoride varnish or 1.23% acidulated phosphate fluoride gel delivered in a fluoride tray are recommended every 3 to 6 months for children who are moderate to high risk of caries.5

Secondary Prevention

Once the enamel begins to break down, the surface will not only present with irregularities but it will also become more porous. If no secondary preventive measure is taken, the enamel will continue to weaken until the surface is cavitated and begins to collapse. Secondary prevention is initiated once the disease state has begun. When the enamel begins to demineralize, fluoride must be provided in order to remineralize and reverse the disease process.12

If the affected area of the enamel remineralizes, the tooth remains intact without further treatment. Once the enamel breaks down, more invasive treatment is recommended in order to preserve the remaining tooth structure. In the primary dentition, losing a tooth can negatively impact the eruptive placement of the permanent teeth. In this way, primary teeth act as place holders for the succedaneous teeth.13

Secondary prevention of dental caries includes primary prevention measures such as using fluoride dentifrice during twice daily brushing. Recommendations may also entail prescription toothpaste with increased fluoride (5,000 ppm for kids), prescription mouthrinse with fluoride, professionally applied fluoride varnish, and oral self-care instruction.5 Silver diamine fluoride (SDF) may also be used to arrest the carious lesion, preventing further breakdown of the enamel. SDF may also be used in cases where the child is at high risk for caries and cavitation of the enamel is apparent. By placing SDF, carious lesions can be arrested, thus stopping the progression of lesion growth.14

Tertiary Prevention

Once the dental decay has progressed, the focus shifts to restoring function, or tertiary prevention. For some, treatment may not be readily available and involve a great length of time waiting to schedule services. In this instance, SDF can minimize the progression of the disease and restore function. Restorative procedures may involve pulpotomies, stainless steel crowns, and/or extractions. These services may need to be delivered in an operating room. Scheduling operating room time can include having to wait for availability at a hospital or clinical facility. During the time spent waiting, the carious lesion(s) can advance and destroy additional tooth surfaces.15 As such, the further along the dental decay progresses, the more invasive the indicated treatment.17 Preventing the progression of decay early on reduces the systemic health risks and minimizes the need for invasive treatment.

The Consequences of Untreated Dental Caries

For children, dental caries is more than just a cavity. Children with tooth decay are more likely to report pain, miss school, and experience a decreased quality of life. Children from lower income households are twice as likely to have dental caries as compared to other children.17 Additionally, the majority of children who receive treatment for dental caries under general anesthesia will present with recurrence of the dental disease within 24 months.17

Many remember Deamonte Driver, a 12-year-old boy who died after the infection in his tooth traveled to his brain and led to sepsis. Instead of an $80 extraction, his untreated caries cost his family $250,000 in medical bills and eventually, his life.18 His death was preventable.

In early stages, dental caries may go unnoticed by parents. After the child reports pain or discomfort, the dental disease may be advanced and require more invasive treatment.17 By preventing caries, the child maintains quality of life and is able to function normally at home, school, and socially. Caries prevention plans must include topical fluoride, in the form of professionally applied treatments, and over-the-counter or prescription fluoride dentifrice and mouthrinse, based on the patient’s assessment and needs.

Safety of Topical Fluoride

Unlike systemic fluoride, topical fluoride remains on the tooth surface to strengthen and remineralize weakened tooth structure. Children should be taught to expectorate fluoride products whether they are used at-home or are professionally applied fluoride treatments in order to prevent accidental ingestion. Following manufacturer dosage recommendations and adhering to treatment processes, such as using a saliva evacuator and remaining with the patient during treatment, also reduce the risk of ingestion. During oral self-care instruction, oral health professionals should review dosage control of at-home fluoride products with parents/caregivers.5

Children ages 1 to 3 should use a smear of fluoride toothpaste about the size of a grain of rice, while those over age 3 can use a pea-sized amount.8 Topical fluoride mouthrinse should not be recommended for children younger than age 6.8 Parents/caregivers should monitor and supervise the oral self-care of children and assist them as necessary.

Community Water Fluoridation

In the US, some states are beginning to remove fluoride from drinking water.19 Children from these areas, including those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds at elevated caries risk, will no longer benefit from the protective features of community water fluoridation and will be at increased risk for not just tooth decay, but the systemic effects of untreated dental caries.

Oral health professionals can serve as advocates for the retention of fluoride in public water systems. The current recommended amount of fluoride used to fluoridate community systems is 0.7 ppm.19 This low dose of supplementation has been proven to prevent dental caries, including among the most vulnerable populations.19

Conclusion

Dental caries remains a widespread and preventable disease that disproportionately affects vulnerable children. By emphasizing individualized risk assessment, appropriate fluoride use, and primary prevention strategies, oral health professionals can help reduce the burden of disease and improve outcomes. As community water fluoridation comes under threat in some regions, it is more important than ever for dental teams to advocate for proven preventive measures and educate families about the essential role of fluoride in maintaining children’s oral health.

References

1. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Quality of Care for Children in Medicaid and CHIP: Findings from the 2019Child Core Set. Available at medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/downloads/performance-measurement/2020-child-chart-pack.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2025.

2. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral Health. Available at cdc.gov/oral-health/prevention/about-fluoride.html. Accessed June 20, 2025.

3. Adeghe E. Integrating pediatric oral health into primary care: a public health strategy to combat oral diseases in children across the United States. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research Updates. 2024;07(01):027-036.

4. Weyant R, Tracy S, Anselmo T, Frantsve-Hawly J, Meyer D. Topical fluoride for caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1279-1291.

5. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride Therapy. Available at aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_FluorideTherapy.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2025.

6. American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form. Available at ada.org/resources/ada-library/oral-health-topics/caries-risk-assessment-and-management. Accessed June 20, 2025.

7. Featherstone J, Crystal Y, Alston P, et al. A comparison of four caries risk assessment methods. Front Oral Health. 2021;2: 1-12.

8. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Caries-Risk Assessment and Management for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Available at aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_CariesRiskAssessment.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2025.

9. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Children’s Oral Health. Available at cdc.gov/oralhealth/basics/childrens-oral-health/index.html. Accessed June 20, 2025.

10. Veiga N, Figueiredo R, Correia P, et al. Methods of primary clinical prevention of dental caries in the adult patient: an integrative review. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;2:1635.

11. Aliakbari E, Gray-Burrows KA, Vinall-Collier KA, et al. Home-based toothbrushing interventions for parents of young children to reduce dental caries: A systematic review. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2021;31:37–79.

12. Nassar Y, Brizuela M. The role of fluoride on caries prevention. Treasure Island, Florida: StatPearls; January 2025.

13. Short M. Head, Neck and Dental Anatomy. 5th ed. Boston: Cengage Group; 2021.

14. Muntean A, Myriam Mzoughi S, Pacurar M, et al. Silver diamine fluoride in pediatric dentistry: effectiveness in preventing and arresting dental caries—a systematic review. Children. 2024;11(4):499.

15. Songur F, Derelioglu S, Yilmaz S, Kosan Z. Assessing the impact of early childhood caries on the development of first permanent molar decays. Front Public Health. 2019;7:186.

16. Patel S, Fantauzzi A, Patel R, Buscemi J, Lee H. Childhood caries and dental surgery under general anesthesia: an overview of a global disease and its impact on anesthesiology. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2023;61:21-25.

17. American Academy of Pediatrics. Treating Tooth Decay. Available at: aapd.org/globalassets/media/policy-center/treatingtoothdecay.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2025.

18. Gavett G. Tragic results when dental care is out of reach. Available at pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/tragic-results-when-dental-care-is-out-of-reach. Accessed June 20, 2025.

19. Johns Hopkins University. Why Is Fluoride in our Drinking Water? Available at publichealth.jhu.edu/2024/why-is-fluoride-in-our-water. Accessed June 20, 2025.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September/October 2025; 23(5):27-31.