MOLEKUUL/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

MOLEKUUL/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Therapeutic Use of Botulinum Neurotoxin Injections

As the popularity of these therapeutic injections increases, oral health professionals should be familiar with their mechanism of action, indications, adverse effects, and evidence for safe and effective use.

This course was published in the January 2019 issue and expires January 2022. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe botulinum neurotoxin’s (BoNT) mechanism of action.

- Identify the indications of use for BoNT injections.

- Discuss the evidence surrounding the therapeutic use of BoNT.

Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) injections are used with increasing frequency to treat a variety of medical conditions. Some therapeutic indications for the orofacial region include oromandibular dystonia, hemifacial spasm, and temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD),1 as well as others related to muscle spasticity and hyperfunction. This is due to the fact that BoNT agents are derived from an extremely potent toxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. This bacterium is responsible for botulism, a rare, but potentially fatal food poisoning associated with immobilization of muscles, which can lead to respiratory paralysis if untreated. The well-known cosmetic use of BoNT type A Botox® reduces facial lines by inducing flaccid paralysis of the muscles that contribute to dynamic rhytids or wrinkles.2 Some nonmuscular indications include sialorrhea and migraine headache, and rely on the toxin’s ability to affect other autonomic nervous system functions besides the neuromuscular junction.1 Oral health professionals will best serve their patients who use these therapies by understanding the agent’s mechanism of action, indications, adverse effects, and evidence for safe and effective use.3

Bacteria have long been used to produce therapeutic agents,4 and the toxins produced by the anaerobe C. botulinum have been isolated into eight serotypes (A-H) and numerous subtypes. Of these eight, BoNT-A and BoNT-B and some of their recombinant subtypes (BoNT/A1, BoNT/A2, BoNT/B1, etc) are the most clinically useful.1 Four products are currently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA): onabotulinumtoxinA, abobotulinumtoxinA, incobotulinumtoxinA, and rimabotulinumtoxinB. The formulations vary in their concentrations, available dose units, and therapeutic applications.5 The variations in specificity and duration of these agents, as well as their limited adverse effects, have been responsible for a virtual explosion of BoNT clinical applications in recent years.1

MECHANISM OF ACTION

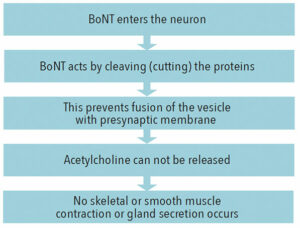

BoNTs are potent neurospecific metalloproteases with exclusive and strong affinity to cholinergic nerve endings, both at the neuromuscular junction and in the autonomic nervous system ganglia where acetylcholine (ACh) is released at the neuro-effector junctions in glands and smooth musculature.1 Upon therapeutic administration, BoNTs have limited diffusion from the site of injection, thus their effects are local. BoNTs lack the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and, therefore, do not affect the central nervous system. BoNTs enter the neuron endings with higher uptake in hyperactive nerve terminals, which are characteristic of several neuromuscular conditions.1

Remarkably, the study of BoNT’s mechanism of action (Figure 1) led to improved understanding of the process of the synaptic neurotransmitter release. Specific neuronal proteins were discovered that bind to the synaptic vesicles containing neurotransmitters (including ACh), moving and fusing them to the synaptic membrane, after which neurotransmitters are released by exocytosis. BoNTs cut three of these presynaptic membrane proteins, thus preventing the exocytosis of ACh and blocking its action at the neuroeffector junctions. The BoNT effect on the nerve terminal is irreversible but temporary due to re-establishing a new neuro-effector connection.1 Unlike other bacterial and plant toxins, the irreversible neuroparalysis caused by BoNTs occurs without cytotoxicity or neurodegeneration, which contributes to its safety, eventual reversibility of paralysis, and patient recovery.1

The ability to block cholinergic transmission at the neuromuscular junction, as well as autonomic innervation of the salivary, sweat, and tear glands; smooth muscles; and sphincters, makes BoNTs an attractive treatment for neuromuscular, gastrointestinal, urologic, and hyperhidrotic disorders. Other potential applications, such as trigeminal neuralgia and other neuropathies, are under active investigation.

STRABISMUS, BLEPHAROSPASM, AND MIGRAINE

Strabismus and blepharospasm, disorders involving the eye muscles and surrounding tissues, were the first FDA-approved indications for BoNT in 1989.6,7 Strabismus is a neuromuscular disorder affecting approximately 4% of the US population that causes blurred or double vision and concomitant psychosocial limitations.8 Corrective therapies include retraining the eyes with glasses/patches, surgical resection or suturing of eye muscles, BoNT injections alone, or the combination of surgery with BoNT injections.9–12 Presently, BoNT injections are considered an alternative to surgery for strabismus,13 equally effective in specific indications and populations depending on age and the severity and characteristics of the treatment.9,10,14

Benign essential blepharospasm is a type of focal dystonia of the periocular muscles that causes excessive intermittent blinking in its mild forms and forced eyelid closure in severe cases.1,15 Most common in women aged 50 to 70, it is associated with other dystonias and Parkinson’s disease. Affected individuals frequently develop secondary psychiatric conditions, sleep disturbances, cognitive impairment, and depression.16 After careful differential diagnosis, both onabotulinumtoxinA and incobotulinumtoxinA formulations are used for treatment, with injections every 6 weeks to 12 weeks. The injections can offer up to 90% effectiveness, making BoNT first-line therapy for benign essential blepharospasm.5,16 Transient adverse effects include hematoma at the injection site, eyelid ptosis, and diplopia.1,16

Migraine is a debilitating disease with severe headaches often preceded by aura, sensitivity to lights/sounds, and accompanied by nausea/vomiting. It is classified as episodic and chronic (less than and more than 15 days per month, respectively). Traditional therapies for migraine include medications for immediate relief and prevention.1,17 These drugs, however, are not always effective, require repeated doses, and exert many adverse effects.17 BoNT-A has been FDA-approved for treatment and prevention of chronic migraine since 2010, and it is thought to act by direct and indirect effect on pain receptors/fibers, neurotransmission in the central nervous system, and an association with endogenous opioid system.1,18 BoNT-A injections in 31 fixed head/neck sites every 3 months are effective in reducing the number and severity of migraine attacks, and demonstrate cumulative effect, requiring less frequent administration in responsive patients.17 Importantly, BoNT-A works synergistically with opioid analgesics and other medications, decreasing their use and preventing opioid tolerance.18

DYSTONIA

Dystonia refers to a variety of neuromuscular movement disorders. They are characterized by involuntary repetitive or patterned movements, intermittent or persistent twisting or postures, and may include spasms or tremor.1,5,19,20 Dystonic symptoms are often associated with other diseases and disorders, most of which profoundly affect quality of life.5,19–22 BoNT injections have been used for more than 25 years to treat some of these disorders with effective symptomatic relief and improved quality of life.1,5,6,16,21 Cervical dystonia is the most common type of focal dystonia, involving voluntary muscles of the neck and shoulders, spasms, tremors, and abnormal positioning of the head.20 These characteristics, accompanied by significant pain in 60% to 90% of cases, contribute to other psychosocial symptoms, such as depression and social withdrawal.23

BoNT injections are the treatment of choice for cervical dystonia, and all four FDA-approved BoNT formulations have strong evidence of sustained effectiveness in alleviating dystonic symptoms and pain.5,23 Effectiveness of peripheral injections of BoNT is attributed not only to ACh blockage at the neuromuscular junction, but also indirect central nervous system blockage of select motor neurons.1 The dosage and choice of muscle-site injections are determined by severity of symptoms and pain, with symptom relief lasting up to 12 weeks.23 Analgesics, anticholinergics, and antidepressants are commonly used to alleviate accompanying symptoms and to bridge intervals between injections. Adverse effects are relatively minor, but include xerostomia and dysphagia, seen more often with BoNT-B.1,5

Oromandibular dystonia is associated with jaw closure, trismus, bruxism, clenching, jaw deviation, and rarely, lingual dystonia, and may impair both speech and swallowing.5,21 Oral pharmacologic agents have limited evidence of effectiveness and many adverse reactions.24 Despite a limited number of studies for BoNT-A injections with variable outcomes,5 it is still considered the treatment of choice for oromandibular dystonia.21 BoNT injections into selected muscles may be done extra- or intraorally.21 Dysphagia is the most common adverse effect, and the need for more comprehensive, controlled studies is emphasized.5

Hemifacial spasm occurs in 10 per 100,000 people, most often in women aged 40 to 60, and is characterized by unilateral involuntary, intermittent, tonic/clonic contractions of the muscles enervated by the facial nerve,.16,25 It is caused by vascular compression of the facial nerve, and treatment options include surgical microvascular decompression of the nerve and less invasive BoNT-A injections, every 3 months to 4 months. Both approaches have an 85% to 90% success rate in relieving symptoms.5,16,25

SIALORRHEA

Sialorrhea (drooling) can occur due to actual increase in saliva production but more often is a symptom of neurological conditions affecting control and coordination of the muscles involved in swallowing.26 In children, the most common association (10% to 38%) is with cerebral palsy,26,27 and in adults it is Parkinson’s disease (70% to 80%).26,28 Other causes include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, post-traumatic encephalopathy, intellectual disability, and neuroleptic medications, such as clozapine.26,29,30 Anterior, over-the-lip margin drooling is associated with perioral irritation and infections, patient discomfort, social embarrassment, and burden on caregivers, while posterior drooling is related to coughing and, most dangerously, aspiration.31

Traditional sialorrhea management includes anticholinergic drugs, which cause significant adverse effects; surgical treatments, such as partial/complete removal or denervation of selected salivary glands, repositioning or ligation of their ducts; and radiation ablation.26,30 In contrast, there is sufficient evidence of effectiveness and safety of BoNT injections into the parenchyma of either parotid or submandibular, or both salivary glands, which together produce about 90% of unstimulated saliva.26,27,30 All four currently FDA-approved BoNT preparations are effectively used; however, BoNT-B may be the best choice for sialorrhea due to its greater affinity to salivary cholinergic neurons and demonstrated reduction in salivary production.26,30

Injections can be done using anatomical landmarks26 or with ultrasound guidance,27 which ensures precise administration and improves safety, especially in cases of anatomical and age-related variations.30 Procedures can be done with or without local anesthesia, but may require sedation or general anesthesia in children.26,27 Most effects are observed in about 2 weeks and can last for 3 months to 6 months.27,29 Repeated injections are necessary, may require higher doses, and can eventually lead to gland atrophy.27 Adverse effects are uncommon and include soreness at the sites of injections, swelling, viscous saliva, and occasionally dysphagia that typically improves over 2 weeks post-procedure.26,27,31

As the goal of BoNT therapy in sialorrhea is a reduction in salivary volume, increased caries risk is possible, particularly among individuals with neurological diseases and special needs. Additionally, decreased salivary flow can slightly lower saliva pH and prevent effective removal of food debris from the mouth.31,32 Indeed, children treated with BoNT-A injections were 1.73 times more likely to develop decay and their salivary pH was significantly lower compared to children treated with placebo.32 However, this study did not compare BoNT treatment to other sialorrhea treatments and no special dental hygiene instruction was provided.32 Subjects in a different study were given oral hygiene instructions, which resulted in no development of new dental caries.31 Comprehensive dental hygiene care using preventive strategies such as fluoride varnish application and patient/caregiver education is crucial in this population.

Extensive analysis of BoNT in the management of sialorrhea demonstrate its effectiveness and safety.26,27,30 However, additional research is needed to determine the optimal number of injections, ideal sites, and the number of salivary glands treated for best therapeutic effect. As procedures are costly and must be repeated at different intervals, BoNT may not be as cost effective as other treatments.26,30

TEMPOROMANDIBULAR DYSFUNCTION

TMD encompasses a broad group of disorders involving the masticatory muscles, temporomandibular joint (TMJ), and associated structures. TMD can be associated with joint and muscle pain and discomfort during regular TMJ function, anterior disk dislocations, joint clicking, and tension-type headaches.3,33–35 One of the hypotheses of TMD development is overactivity and imbalance of muscular function.33,35 Hyperactivity and long-lasting tension in the muscles of mastication are thought to also contribute to tension-type headaches.34 This etiology suggests the possibility of using BoNT injections to reduce muscle tension. This less-invasive treatment has been tried in the management of muscle pain and joint clicking,33 anterior joint dislocation,35 and tension-type headaches.34 BoNT-A injections in the masseter muscles bilaterally resulted in a decrease in the number of muscle and tension-type headaches pain episodes, pain intensity and duration, and decreased use of analgesics.34 Injections into the lateral pterygoid on the side of joint clicking and dislocation resulted in disappearance of the click 2 weeks to 2 months post-treatment.33 Spontaneous frequent TMJ dislocations in patients who were not good candidates for surgery were successfully treated with a single injection of BoNT-A into lateral pterygoid and this improvement was observed up to 2 years after treatment.35

While BoNT injections are less invasive than surgical treatment options, possible complications include hemorrhage due to close location of the TMJ to the maxillary artery and pterygoid plexus of veins. Intraoral injections can minimize the risk.33 Other side effects are dysphagia, nasal speech, nasal regurgitation, and dysarthria. These are generally mild and can be minimized by keeping patients in a vertical position for several hours post-injection to reduce diffusion of BoNT into adjacent tissues.35 Despite reports of successful TMD management, current evidence is insufficient for specific recommendations using BoNT.3 BoNT injections can be suggested as a method of choice, but not the primary treatment for TMD; more long-term studies involving larger patient numbers are needed to confirm the effectiveness of this method.33,34

CONCLUSION

The therapeutic use of BoNT injections as safe and effective for a variety of medical/dental uses is supported by a large body of evidence. Careful extraoral/intraoral examination and recognition of signs/symptoms of medical and dental conditions that may be treated successfully with BoNT will lead to appropriate referral and evaluation, prompt diagnosis, and timely, appropriate treatment. Oral health professionals should be familiar with medical indications and modes and frequency of BoNT treatment benefits. For indications that may affect dental treatment, scheduling dental treatment to coincide with timing of maximum pharmacological effect of BoNT will allow for safe, comfortable experiences and assure best therapeutic outcomes.21,26

REFERENCES

- Pirazzini M, Rossetto O, Eleopra R, Montecucco C. Botulinum neurotoxins: biology, pharmacology, and toxicology. Pharmacol Rev. 2017;69:200–235.

- Harnois PT. The therapeutic and esthetic uses of botulinum toxin in dentistry. Alpha Omegan. 2015;108(3):30–37.

- Clark GT, Stiles A, Lockerman LZ, Gross SG. A critical review of the use of botulinum toxin in orofacial pain disorders. Dent Clin North Am. 2007;51:245–261.

- Carruthers A, Kane MAC, Flynn TC, et al. The convergence of medicine and neurotoxins: a focus on botulinum toxin type a and its application in aesthetic medicine—a global, evidence-based botulinum toxin consensus education initiative: part i: botulinum toxin in clinical and cosmetic practice. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:493–509.

- Hallett M, Albanese A, Dressler D, et al. Evidence-based review and assessment of botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of movement disorders. Toxicon. 2013;67(Supplement C):94–114.

- Monheit GD, Pickett A. AbobotulinumtoxinA: a 25-year history. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(Suppl 1):S4–S11.

- Scott AB. Botulinum toxin injection of eye muscles to correct strabismus. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1981;79:734–770.

- American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. What is strabismus and how common is it? Available at: https://aapos.org/ terms/show/14. Accessed December 7, 2018.

- Tuğcu B, Sönmezay E, Nuhoğlu F, Özdemir H, Özkan SB. Botulinum toxin as an adjunct to monocular recession-resection surgery for large-angle sensory strabismus. J Am Assoc Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2017;21:117–120.

- Wan MJ, Mantagos IS, Shah AS, Kazlas M, Hunter DG. Comparison of botulinum toxin with surgery for the treatment of acute-onset comitant esotropia in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;176:33–39.

- Kassem A, Xue G, Gandhi NB, Tian J, Guyton DL. Adjustable suture strabismus surgery in infants and children: a 19-year experience. J Am Assoc Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2018;22:174–178.

- Issaho DC, Carvalho FR de S, Tabuse MKU, Carrijo-Carvalho LC, de Freitas D. The use of botulinum toxin to treat infantile esotropia: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:5468–5476.

- Rowe FJ, Noonan CP. Botulinum toxin for the treatment of strabismus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3:CD006499.

- Gursoy H, Basmak H, Sahin A, Yildirim N, Aydin Y, Colak E. Long-term follow-up of bilateral botulinum toxin injections versus bilateral recessions of the medial rectus muscles for treatment of infantile esotropia. J Am Assoc Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2012;16:269–273.

- What is Blepharospasm? Available at: blepharospasm.org/blepharospasm-what.html. Accessed December 7, 2018.

- Green KE, Rastall D, Eggenberger E. Treatment of blepharospasm/hemifacial spasm. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2017;19:41.

- American Migraine Foundation. Migraine Disorders, Studies and Symptoms. Available at: https://americanmigrainefoundation.org/ ?s=Migraine+Disorders%2C+Studies+and+Symptoms. Accessed December 7, 2018.

- Matak I, Lacković Z. Botulinum toxin A, brain and pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;119(Supplement C):39–59.

- Dystonia Medical Research Foundation. What is dystonia? Available at: dystonia-foundation.org/what-is-dystonia/. Accessed December 7, 2018.

- Albanese A, Bhatia K, Bressman SB, et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc. 2013;28:863–873.

- Comella CL. Systematic review of botulinum toxin treatment for oromandibular dystonia. Toxicon. 2018;147:96–99.

- Jankovic J. An update on new and unique uses of botulinum toxin in movement disorders. Toxicon. 2018;147:84–88.

- Camargo CHF, Cattai L, Teive HAG. Pain relief in cervical dystonia with botulinum toxin treatment. Toxins. 2015;7:2321–2335.

- Teemul TA, Patel R, Kanatas A, Carter LM. Management of oromandibular dystonia with botulinum A toxin: a series of cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;54:1080–1084.

- Rosenstengel C, Matthes M, Baldauf J, Fleck S, Schroeder H. Hemifacial spasm. Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 2012;109:667–673.

- LakraJ AA, Moghimi N, Jabbari B. Sialorrhea: anatomy, pathophysiology and treatment with emphasis on the role of botulinum toxins. Toxins. 2013;5:1010–1031.

- Gok G, Cox N, Bajwa J, Christodoulou D, Moody A, Howlett DC. Ultrasound-guided injection of botulinum toxin A into the submandibular gland in children and young adults with sialorrhoea. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:231–233.

- Martínez-Poles J, Nedkova-Hristova V, Escribano-Paredes JB, et al. Incobotulinumtoxin A for sialorrhea in neurological disorders: a real-life experience. Toxins. 2018;10:6.

- Restivo DA, Panebianco M, Casabona A, et al. Botulinum toxin A for sialorrhoea associated with neurological disorders: evaluation of the relationship between effect of treatment and the number of glands treated. Toxins. 2018;10:2.

- Dashtipour K, Bhidayasiri R, Chen JJ, Jabbari B, Lew M, Torres-Russotto D. RimabotulinumtoxinB in sialorrhea: systematic review of clinical trials. J Clin Mov Disord. 2017;4(1):9.

- Møller E, Pedersen SA, Vinicoff PG, et al. Onabotulinumtoxin A treatment of drooling in children with cerebral palsy: a prospective, longitudinal open-label study. Toxins. 2015;7:2481–2493.

- Dos Santos BF, Dabbagh B, Daniel SJ, Schwartz S. Association of onabotulinum toxin A treatment with salivary pH and dental caries of neurologically impaired children with sialorrhea. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2016;26:45–51.

- Emara AS, Faramawey MI, Hassaan MA, Hakam MM. Botulinum toxin injection for management of temporomandibular joint clicking. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;42:759–764.

- Pihut M, Ferendiuk E, Szewczyk M, Kasprzyk K, Wieckiewicz M. The efficiency of botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of masseter muscle pain in patients with temporomandibular joint dysfunction and tension-type headache. J Headache Pain. 2016;17:29.

- Fu K-Y, Chen H-M, Sun Z-P, Zhang Z-K, Ma X-C. Long-term efficacy of botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of habitual dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;48:281–284.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2019;17(1):26–28,31.

This was an excellent article well documented and extremely current. As health care professionals we all need to become aware of the new aspects before our profession . I have been lucky to have attended lectures nationally and internationally presented by these two amazing speakers. Thank you Sandra and Anna for an all your work and of course Dimensions for publishing these and many informative articles.

Thank you so much for sharing your opinion of our article, Nancy! We are happy you found it informative and contributing to the dental professionals’ knowledge.