The Role of Oral Health Professionals in the Opioid Epidemic

Clinicians need to understand the signs and symptoms of opioid abuse and engage in efforts to curtail it.

This course was published in the February 2018 issue and expires February 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the etiology of the opioid epidemic in the United States.

- List the oral and systemic complications of opioid abuse.

- Discuss the US Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations and guidelines for prescribing opioids.

- Explain analgesic prescribing recommendations for acute post-operative dental pain.

An increase in the use of legally prescribed opioid pain medications has significantly contributed to the overdose epidemic. Today, the number of opioid prescriptions written in the US is four times higher than in 1999.6 While many people use opiates legally to control chronic pain, the risk of addictions is high.6 Because opiates stimulate the release of dopamine in the brain,7 respiratory suppression may occur, which can cause death.8Unintentional overdose may occur because patients may develop a higher tolerance to the analgesic, or pain-relieving, properties than to the respiratory depressant properties, so a dosage high enough to address pain may exceed the patient’s tolerance to respiratory depression, resulting in respiratory arrest.9 The same mechanisms that make the drug an effective pain management tool are also most dangerous when methods are used to increase their onset, such as snorting or injecting.6 Current evidence suggests that the recent spike in heroin use may be due to the mounting chemical tolerance of prescribed opioids, causing users to switch to heroin, which is often less expensive and, in some cases, easier to obtain.6 Prescriptions alone are not to blame, however, as the etiology of the epidemic is multifactorial, including greater social acceptance of recreational drug use and widespread pharmaceutical marketing.6 Health care professionals need to be knowledgeable in their understanding of opioid abuse and proactive in patient and pain management.

Several online drug screening tools are available to help practitioners identify high-risk patients. The National Institute on Drug Abuse website—drugabuse.com—has links to several screening resources.10 Medical practitioners can register with their state’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP), an electronic database that tracks controlled substances and provides data on medications, high dosages, and prescriptions from other providers.11,12 In many states, PDMPs can be accessed by an individual designated by the prescriber, such as a dental hygienist.13 The CDC recommends checking the PDMP before every opioid prescription and rechecking every 3 months.12 Individuals at high risk for opioid overdose include those who: already have an opioid dependence or reduced tolerance; inject opioids; use prescription opioids; take opioids in combination with other sedating substances; use opioids and have medical conditions, such as depression, human immunodeficiency virus infection, or liver or lung disease; and have household members who possess opioids.8

Closely monitoring of at-risk patients’ oral conditions and educating them about the potential dangers of opioid use can help patients prevent unintentional opioid abuse.13 For patients with a known opioid addiction, it is important to have resources available to assist with addiction awareness, withdrawal symptoms, and treatment options.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Signs of an opioid overdose include pinpoint pupils, unconsciousness, and respiratory depression.8 In the event of an opioid overdose, basic life support and administration of naloxone, the opioid antagonist, can prevent death. Naloxone is effective in multiple delivery routes including intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intranasal.8 While naloxone was previously only available in health care settings, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the administration of naloxone in a hand-held auto-injector and a nasal spray.14,15

For patients with a known dependence on opioids, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends various treatments including psychological support; opioid maintenance treatments, such as methadone and buprenorphine; and reinforced detoxification with opioid antagonists like naltrexone.8 Medical support through a withdrawal period can help patients successfully navigate symptoms.16,17

ORGANIZATIONAL ACTION

The breadth of the opioid epidemic has elicited action from both the FDA and CDC. The FDA has developed a comprehensive action plan to eliminate opioid abuse.18 The FDA’s Opioids Action Plan will expand use of advisory committees before approving new drug applications; develop warnings and safety information for immediate-release opioid labels; strengthen post-market requirements for producing data on the long-term impact of using the drug; update risk evaluation and mitigation strategy program; expand access to abuse-deterrent formulations; broaden access to overdose treatment and encourage safe prescribing; and reassess the risk-benefit approval framework for opioid use to incorporate the public health impact of opioid abuse in approval decisions.18

The new CDC guidelines provide recommendations for primary care clinicians who prescribe opioids for chronic pain and include when to begin or continue opioid use for chronic pain, opioid selection, dosage, duration, discontinuation, and assesment of risk and harms of opioid use.19 One of the main goals of the CDC guidelines is to facilitate improved communication between providers and patients about opioid therapy.20 Because treatment options and recommendations for chronic pain should include nonopioid medications as a first-line of defense, the CDC provides information on common medications for pain (Table 1).21

PRESCRIBING PATTERNS

As oral diseases and their treatment often cause significant pain, dentists’ prescription practices may impact the opioid epidemic.22Combination medications containing acetaminophen (APAP) and hydrocodone or APAP-hydrocodone are the most commonly prescribed analgesics among oral and maxillofacial surgeons.23 Among those surveyed by the American Dental Association in 2011, 85% of oral and maxillofacial surgeons reported prescribing an average of 10 tablets to 20 tablets of hydrocodone/acetaminophen, a supply intended to treat 2 days to 5 days of post-operative pain.22

Dentists are in a unique position to screen for opioid abuse. A 2016 survey of 87 dentists that assessed opioid prescribing practices found that 44% screened patients for prescription drug abuse.24 Routine consultation with the PDMP is an effective way to reduce opioid prescribing in the dental setting. A New York dental urgent care center experienced a 78% reduction in total opioid prescriptions after implementation of a mandatory PDMP consultation.25 Survey data from 2016 revealed the most cited reason for not using the PDMP was “unawareness of its existence,” reported by 72% of respondents.24 Awareness of the PDMP must increase in order to deter prescription drug abuse.

COMBINATION PROTOCOLS

Concerns regarding the adverse effects of opioid medications have prompted a number of studies evaluating the efficacy of pain relief achieved by combining analgesic medications. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are considered first-line treatment for dental pain, which has inflammatory origins.26 It is hypothesized that combining analgesics provides “multimodal analgesia” by offering additive effects of drugs that have different mechanisms of action.27 Ibuprofen is the most commonly used NSAID.23 Acetaminophen is an analgesic medication with an unknown mechanism of action that possesses antipyretic activity but limited anti-inflammatory action.23

A Cochrane systematic review was conducted that compared the efficacy of single dose ibuprofen plus acetaminophen.28 Combining ibuprofen (400 mg) and acetaminophen (1,000 mg) produced better pain relief over 8 hours than a single dose of ibuprofen (400 mg) or acetaminophen (1,000 mg) alone.28 Furthermore, 400 mg of ibuprofen combined with 1,000 mg APAP produced more pain relief than medications containing APAP and codeine. This combination produced a median duration of pain relief for 8.3 hours.29 The 400 mg ibuprofen/1,000 mg APAP combination appears to provide optimal dosing, with less efficacy reported for lower dosage combinations and no additional efficacy reported for higher doses of either ibuprofen or APAP alone.29

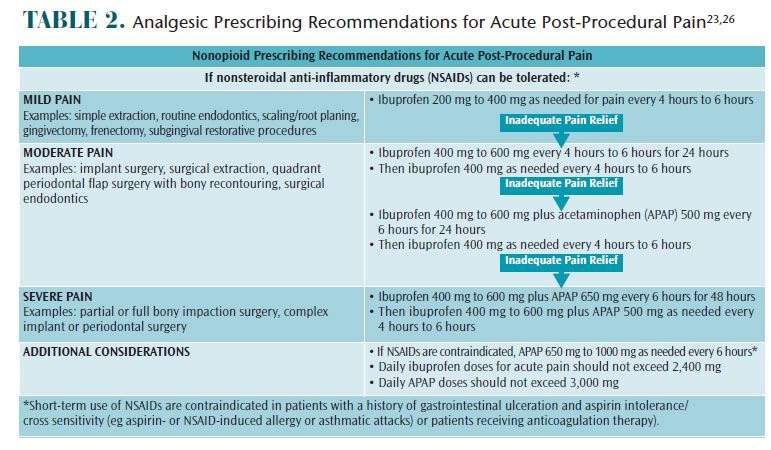

There is a potential for acetaminophen toxicity. Current guidelines suggest that while a single dose of 1,000 mg APAP is safe, repeated dosing of APAP should be limited to 500 mg every 4 hours or 650 mg every 6 hours with a maximum daily dose of 3,000 mg. The total dose of ibuprofen should not exceed 2,400 mg per day.23 Adverse effects of APAP-codeine combination medications were more frequently encountered than adverse effects associated with the APAP-ibuprofen combination.23 Thus, it can be argued that the use of an appropriately dosed combination of ibuprofen and acetaminophen is not only safer but also more effective than an APAP-opioid combination medication. Furthermore, combining ibuprofen and acetaminophen produces long-lasting pain relief with few adverse effects. Table 2 shows nonopioid recommended protocols for patients who can tolerate NSAIDs and those who cannot.23,24,26

![]() ADDITIONAL STRATEGIES

ADDITIONAL STRATEGIES

Clinicians should consider additional pain management approaches that have demonstrated efficacy in alleviating post-operative pain. These include the use of a long-acting anesthetic, a preoperative analgesic, or a combination of both. The long-acting anesthetic 0.5% bupivacaine plus 1:200,000 epinephrine provides 6 hours to 9 hours of soft tissue and periosteal anesthesia.30 The use of bupivacaine can reduce the need to use rescue analgesia during the early post-operative hours.31 More important, the use of bupivacaine (compared to 2% lidocaine) administered near the end of periodontal surgical procedures reduced the amount of opioid analgesics needed.32

The administration of preoperative analgesia has long demonstrated a benefit in reducing post-operative pain.33 Preoperative analgesia may produce 4 hours to 6 hours of post-operative pain relief.34 An optimal protocol may be the combination of a long-acting local anesthetic with a preoperative analgesic, which provides 6 hours to 7 hours of post-operative pain relief.34

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals need to understand the signs and symptoms of opioid abuse and engage in efforts to curtail it. Consulting statewide PDMPs and evaluating current prescribing practices are steps in the right direction. An evidence-based approach to the treatment of post-procedural pain is paramount to providing effective pain relief without contributing to the opioid epidemic.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid Basics: Understanding the epidemic. Available at: cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/. Acessed January 12, 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Provisional Counts of Drug Overdose Deaths, as of 8/6/2017. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/data/health_ policy/monthly-drug-overdose-death-estimates.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64: 1378–1382.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER. Available at: wonder.cdc.gov/. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- The White House. Fact Sheet: Obama Administration Announces Additional Actions to Address the Prescription Opioid Abuse and Herion Epidemic. Available at: whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/03/29/fact-sheet-obama-administration-announces-additional-actions-address.htm. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s Addiction to Opioids: Heroin and Prescription Drug Abuse. Available at: drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Drugabuse.com. The Effects of Opiate Use. Available at: http://drugabuse.com/library/the-effects-of-opiate-use/#short-term-effects-of-opiates. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- World Health Organization. Management of Substance Abuse. Available at: who.int/substance_ abuse/information-sheet/en/. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Hayhurst CJ, Durieux ME. Differential opioid tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a clinical reality. Anesthesiology.2016;124:483–488.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Chart of Evidence-Based Screening Tool for Adults and Adolescents. Available at: drugabuse.gov/ nidamed-medical-health-professionals/tool-resources-your-practice/screening-assessment-drug-testing-resources/chart-evidence-based-screening-tools-adults. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Why Guidelines for Primary Care Providers? Available at: cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/guideline_ infographic-a.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs. Available at: cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pdmp_factsheet-a.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2018

- American Dental Association. A Message from the ADA President: Dentistry’s Role in Preventing Prescription Opioid Abuse. Available at: ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2016-archive/july/a-message-from-the-ada-president. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Food and Drug Administration. Evzio Label. Available at: accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_ docs/label/2014/205787Orig1s000lbl.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Food and Drug Administration. Evzio (Naloxone Auto-Injector) Approved to Reverse Opioid Overdose. Available at: fda.gov/ drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm391449.htm. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- American Addiction Centers. Opiate Withdrawal Timeline. Available at: http://americanaddictioncenters.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/opiate-withdrawal-timeline.png.pagespeed.ce.9zoZ2E-usH.png. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- American Addiction Centers. Heroin Withdrawal Timeline, Symptoms and Treatment. Available at: http://americanaddictioncenters.org /withdrawal-timelines-treatments/heroin/. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Food and Drug Administration. Fact Sheet—FDA Opioids Action Plan. Available at: fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/FactSheets/ucm484714.htm. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–49.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. Available at: cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/ guidelines_factsheet-a.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonopioid Treatments for Chronic Pain. Available at: cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/alternative_ treatments-a.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2018.

- Denisco R, Kenna G, O’Neil M, et al. Prevention of prescription opioid abuse: the role of the dentist. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:800–810.

- Moore P, Hersh E. Combining ibuprofen and acetaminophen for acute pain management after third-molar extractions: translating clinical research to dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013:144:898–908.

- McCauley JL, Leite RS, Melvin CL, Fillingim RB, Brady KT. Dental opioid prescribing practices and risk mitigation strategy implementation: identification of potential targets for provider-level intervention. Subst Abus. 2016;37:9–14.

- Rasubala L, Pernapati L, Velasquez X, Burk J, Ren YF. Impact of a mandatory prescription drug monitoring program on prescription of opioid analgesics by dentists. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0135957.

- Hersh EV, Kane WT, O’Neil MG. Prescribing recommendations for the treatment of acute pain in dentistry. Compen Contin Educ Dent Suppl. 2011;32:24–30.

- Mehlisch DR. The efficacy of combination analgesic therapy in relieving dental pain. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:861–871.

- Moore R, Derry S, Aldington D, Wiffen P. Single-dose oral analgesics for acute postoperative pain in adults—an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD011603.

- Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA. Single dose oral ibuprofen plus paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD010210.32.

- Moore PA, Hersh EV. Local anesthetics: pharmacology and toxicity. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54:587–599.

- Tharke A, Bhate K, Kathariya R. Comparison of 4% articaine and 0.5% bupivacaine anesthetic efficacy in orthodontic extractions: prospective, randomized crossover study. Acta Anaesthesiologica Taiwanica. 2014;52:59–63.

- Gordon SM, Mischenko AV, Dionne RA. Long-acting local anesthetics and perioperative pain management. Dent Clin N Am. 2010;54:611–620.

- Wall PD. The prevention of postoperative pain. Pain. 1988;33:289–290.

- Dionne RA, Gordon SM. Changing paradigms for acute dental pain: prevention is better than prn. Prevention.2015;43:665–662.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2018;16(2):50-53.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS ADDITIONAL STRATEGIES

ADDITIONAL STRATEGIES