The Nutritional Link to Periodontal Health

With periodontitis affecting nearly half of American adults, understanding how vitamins, minerals, and nutrients influence inflammation and healing can help dental hygienists guide patients toward healthier smiles.

This course was published in the November/December 2025 issue and expires December 2028. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 490

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the impact of nutrition on periodontal health.

- Define macro- and micronutrients.

- Discuss the role of dental hygienists in providing nutritional counseling to patients.

Periodontitis is ubiquitous in the United States, affecting 60% of those age 65 and older and more than 40% of individuals age 30 and older.1 According to the American Academy of Periodontology, in 2018, the cost of untreated periodontitis was $154 billion.2 Of these costs, approximately $3.49 billion is related to direct treatment expenses, with an additional $150.58 billion in indirect costs related to complications and lost productivity.2 Dental hygienists are integral to the prevention of this costly disease.

Nutrition is a key factor in the development of periodontitis. Macronutrients and micronutrients may indirectly alter patients’ ability to develop structures in the oral cavity, resist inflammation, or repair tissue or wounds.3 Dental hygienists should be familiar with these nutrients and their impact on periodontal health, so they can help their patients understand how the foods they eat contribute to periodontal health.

Dental hygienists assess periodontitis risk by collecting information about patients’ pharmacologic history, including vitamins, minerals, nutritional supplements, herbs, probiotics, and complementary therapies; social history, such as physiologic stress and alcohol and tobacco use; and nutritional history.2-4 Evaluating patients’ nutritional history and dietary practices is crucial for vulnerable populations such as those who are edentulous, elderly, pregnant, or low income, and those with chronic disease or physiologic disorders that interfere with food consumption.3 These assessments may reveal nutrient deficits that contribute to a patient’s periodontal status.

Micronutrients, through the use of macronutrients, facilitate all metabolic reactions. Macronutrients provide energy that micronutrients lack, therefore consuming them together is most favorable to supporting health. An imbalance of any nutrient may disrupt the immune defense response and processes for growth, repair, or maintenance within the oral cavity.

Macronutrients

Each macronutrient impacts the periodontium via the immune or endocrine systems. Structural proteins in the periodontal ligament and enzyme reactions split into amino acids. Amino acids are building blocks for growth, maintenance, and repair of gingival tissue and cells in the oral cavity. Inadequate intake of proteins impairs responses to inflammation and infection and delayed wound healing.3

Carbohydrates are required to synthesize connective tissues, red blood cells, and neurological functions.5 Biofilm, which contains carbohydrates, forms calculus, a habitat for periodontal pathogens. Lipids are necessary for the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. Lipids include omega-3-fatty-acids, which may decrease the inflammation associated with periodontal diseases. Excessive consumption of lipids and carbohydrates may lead to increased adipose tissue and higher levels of inflammatory agents linked to obesity and periodontal diseases.6 Consuming fiber may provide a protective influence on these inflammatory agents within the periodontium.6

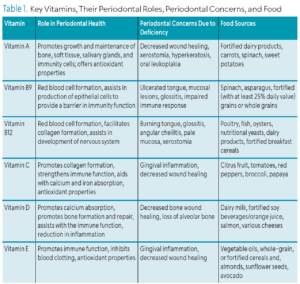

Vitamin A

An inverse relationship has been demonstrated between the consumption of vitamin A and periodontitis risk.7,8 Vitamin A is required for the growth of bone and soft tissue as well as development and maintenance of salivary glands. Additionally, it promotes odontoblasts for bone growth of the periodontium, preserves mucosal tissue, and controls specific cell differentiation involving immunity. The antioxidants from vitamin A may prevent free radicals from causing damage to the oral cavity.3

A deficiency in vitamin A presents as gingivitis, gingival hypoplasia, growth of crevicular epithelium, and resorption of alveolar bone.9 In addition, the use of vitamin A after nonsurgical periodontal therapy supports healing and significantly decreases pocket depths among nonsmokers compared to smokers.10

Vitamin B Complex

Vitamin B complex is critical in cell metabolism, production, and repair. Research has found that folic acid/folate (B9) and cobalamin (B12) contribute to healthy immune function, including maintaining regular concentration of red blood cells and epithelial cells.3,11,12 Signs and symptoms of folate deficiency may include ulcers on the tongue or gingival epithelia, as well as the tongue swelling, lacking papilla, and fiery red color.3 Smokers have low serum vitamin B9 levels, which may increase the severity of periodontitis.13,14

Individuals with periodontitis have lower serum B12 levels than healthy individuals.11 Cobalamin facilitates collagen formation, synthesis of red blood cells, development of the nervous system, and support of metabolic activities.15 While B12 deficiency signs and symptoms are similar to B9, burning tongue arises before other signs.3 Greater clinical attachment loss and tooth loss are associated with low serum B12 levels.12 Vitamin B complex supplementation is associated with significantly higher mean clinical attachment gain at shallow and deep periodontal pockets after nonsurgical periodontal therapy.16 However, excessive folate intake from supplementation might mask a B12 deficiency.3

Vitamin C

An antioxidant, vitamin C plays a vital role in maintaining and restoring healthy connective tissue in the periodontium.3 An inverse relationship exists between vitamin C and periodontitis severity.17 The discovery of scurvy demonstrated that decreased vitamin C levels were associated with raised, painful gingival bleeding and tooth mobility. A shortage of vitamin C leads to weakened collagen, poor wound healing, and gingivitis. Individuals who smoke require more vitamin C than nonsmokers.3

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is required for growth of bone and teeth and remineralization and regulation of blood calcium and phosphorus levels. As such, vitamin D deficiency may result in brittle or misshaped bones.3 Working with osteoblasts to produce new bone and produce collagen, vitamin D also contributes to the formation of red blood cells, regulation of serum calcium levels to maintain cardiac and neuromuscular operations, and immune function.3,6

Rickets, which is caused by a vitamin D deficiency, weaken the trabeculae of the alveolar bone. In infants and children, vitamin D deficiency may cause delayed tooth eruption and lead to smaller-sized molars.3 A deficiency in vitamin D may also hinder wound healing, causing poor treatment outcomes following periodontal surgery. Adequate vitamin D intake is associated with healthier periodontium including less inflammation and decreased risk of tooth loss.18

Vitamin E

Vitamin E is a key antioxidant that helps the periodontium resist inflammation. It prevents hemolysis of red blood cells by keeping the cell membrane intact and enhances the growth of white blood cells. In large quantities, it acts as a blood thinner.3 Higher vitamin E levels are linked to less severe periodontitis.19 The insufficient intake of vitamin E diminishes antioxidants thus increasing the risk of periodontal inflammation and bleeding on probing, as well as decreasing ability of cell membranes to protect the mucosa.3,20 Table 1 provides an overview of vitamins and their relationship to periodontal health (page 29).

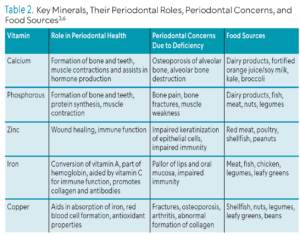

Calcium and Phosphorus

Vitamin D, calcium, and phosphorus work together to support hard tissue formation and maintenance. Teeth and bone structure contain 99% of calcium and about 85% of the phosphorus in the body. Calcium deficiency may result in incomplete calcification of teeth, abnormalities in teeth and bones, periodontal diseases, and altered alveolar bone integrity leading to tooth loss.3

Low levels of calcium are associated with an increased risk of periodontal diseases.21 Vitamin D and calcium deficiencies may contribute to the development of osteoporosis, which could decrease in calcium in alveolar bone and, ultimately, result in tooth loss.3 Furthermore, vitamin D and calcium improve the outcomes of periodontal therapy.22 Bone pain, bone fractures, and muscle weakness are symptoms of phosphorus deficiency.6 However, a greater risk for periodontal inflammation may be linked with increased calcium and phosphate salivary levels.23 Table 2 provides a review of key minerals and their role in periodontal health.

Trace Minerals

Zinc, iron, and copper are trace minerals associated with immune response and maintenance of oral tissues.3 To date, research has not shown an association between these trace minerals and periodontitis.5 Zinc may play a role in maintaining periodontal health by providing antioxidant properties for immune response and wound healing.24,25 Iron assists in conversion of betacarotene to vitamin A; synthesis of hemoglobin, enzymes, and collagen; production of antibodies; activation of oxidative reactions within cells; and promotion of immune function.3,5 Lastly, copper’s role is essential for the formation of red blood cells, connective tissue, bones, and enzymatic oxidative reactions, as well as the production of neurotransmitters and immune integrity.3,6 Increased copper buildup may damage periodontal tissue and possibly increase tissue destruction through an inflammatory reaction.26

Dental Hygienist’s Role in Nutritional Counseling

Proper nutrition may increase patients’ immune response, helping to improve oral health. Both the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Dental Hygienists’ Association support interprofessional collaboration for evidence-based oral disease prevention and intervention.27,28

Proper nutrition may increase patients’ immune response, helping to improve oral health. Both the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Dental Hygienists’ Association support interprofessional collaboration for evidence-based oral disease prevention and intervention.27,28

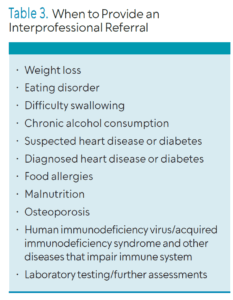

Dental hygienists should perform nutritional counseling to prevent or reduce periodontal diseases. A referral to physicians, registered dietitians, or registered nutritionists is recommended when a patient’s nutritional counseling needs are beyond the scope of dental hygiene practice. Table 3 lists medical conditions that require an interprofessional referral. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (eatright.org) helps patients find a nutrition expert in their area.

The Commission on Dental Accreditation requires dental hygienists to have foundational knowledge in caries prevention and nutrition for “…analysis and synthesis of the interrelationships of the body systems…”30 Dental hygienists should advocate for dedicated questions about nutrition and dietary habits on medical or dental history intake forms.

Motivational interviewing should also be part of the conversation for nutritional intake and counseling. Patients should be evaluated using caries management by risk assessment and dietary analysis to screen for food sources that would contribute negatively to patients’ disease process, such as an abundance of processed foods. Patients should also be screened for any signs of a nutrient deficiency that may need a referral to another healthcare provider or that may impact treatment outcomes.

Discussion on the role of nutrition and food in periodontal disease development, progression, and healing after periodontal therapies is part of nutritional counseling. Dietary recommendations may include consuming more whole nutrient dense foods with antioxidant properties,such as fruits and vegetables. Furthermore, information on the relationship between antioxidants and periodontium healing may be included in the conversation.

After nonsurgical periodontal therapy, potential recommendations include foods with high beta-carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol), folic acid, vitamin D, and omega-3 fatty acids.10,31-33 Additionally, dental hygienists may refer patients to receive further guidance on nutrient supplementation as part of conjunctive therapy with nonsurgical periodontal therapy. In summary, promoting balanced dietary patterns rich in nutrients and antioxidants and identifying when to provide an interprofessional referral play a crucial role in maintaining optimal oral health.

Conclusion

Nutritional modifications are a critical component of preventing or healing from periodontal diseases. Dental hygienists are well-positioned to educate patients about the relationship between nutrition and periodontal health. They can assess patients’ medical history, social history, nutritional history, as well as their social and dietary habits. These assessments help determine the need for dietary counseling and/or referral to an interprofessional provider. These services build trust between practitioners and patients, contribute to a positive image for the profession, and confirm the dental hygienist as a member of the patient’s interprofessional healthcare team.

References

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Periodontal Disease in Adults (Age 30 or Older). Available at nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/periodontal-disease/adults. Accessed October 6, 2025.

- American Academy of Periodontology. Economist Impact Report: Gum Disease. Available at perio.org/for-patients/economist-impact-report-gum-disease. Accessed October 6, 2025.

- Stegeman C, Ratliff Davis J. The Dental Hygienist’s Guide to Nutritional Care. 5th ed. New York: Elsevier; 2019.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at adha.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2025.

- Najeeb S, Zafar MS, Khurshid Z, Zohaib S, Almas K. The role of nutrition in periodontal health: an update. Nutrients. 2016;8:530.

- Sroda R, Reinhard T. Nutrition for Dental Health. 3rd ed. Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Barlett Learning; 2018.

- Zhou S, Chen J, Cao R. Association between retinol intake and periodontal health in US adults. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23:61.

- Blaner W. Vitamin A and provitamin A carotenoids. In: Marriott BP, Birt DF, Stallings VA, Yates AA, eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. 11th ed. Hoboken, New Jersy: Wiley-Blackwell; 2020.

- Shaw J. The relation of nutrition to periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 1962;41:264-274.

- Dodington D, Fritz P, Sullivan P, Ward W. Higher intakes of fruits and vegetables, ββ-carotene, vitamin C, αα-tocopherol, EPA, and DHA are positively associated with periodontal healing after nonsurgical periodontal therapy in nonsmokers but not in smokers. J Nutr. 2015;145:2512-2519.

- Mayank H, Kumar Malik P, Madaan Hans V, Chug A, Kumar M. Serum levels of various vitamins in periodontal health and disease – a cross sectional study. J Oral Biol Craniofacial Res. 2023;13:471-475.

- Zong G, Holtfreter B, Scott A. Serum vitamin b12 is inversely associated with periodontal progression and risk of tooth loss; a prospective cohort study. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43:2-9.

- Erdemir E, Bergstrom J. Effect of smoking on folic acid and vitamin B12 after nonsurgical periodontal intervention. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:1074-1081.

- Erdemir E, Bergstrom J. Relationship between smoking and folic acid, vitamin B12 and some haematological variables in patients with chronic periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:878-884.

- Stabler S. Clinical practice. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2013;137:149-160.

- Neiva R, Al-Shammari K, Nociti, Jr F, Soehren S, Wang H. Effects of vitamin-B complex supplementation on periodontal wound healing. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1084-1091.

- Socransky S, Haffajee A, Cugini M, Smith C, Kent R. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:134-144.

- Jimenez M, Giovannucci E, Krall Kaye E, Joshipura KJ, Dietrich T. Predicted vitamin D status and incidence of tooth loss and periodontitis. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:844-852.

- Zong G, Scott A, Griffiths H, Zock P, Dietrich T, Newson R. Serum α tocopherol has a nonlinear inverse association with periodontitis among US adults. J Nutr. 2015;145:893-899.

- Willershausen B, Ross A, Försch M, Willershausen I, Mohaupt P, Callaway A. The influence of micronutrients on oral and general health. Eur J Med Res. 2011;16:514.

- Adegboye A, Boucher B, Kongstad J, Fiehn N, Christensen L, Heitmann B. Calcium, vitamin D, casein and whey protein intakes and periodontitis among Danish adults. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19:503-510.

- Garcia M, Hildebolt C, Miley D, et al. One-year effects of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2011;82:25-32.

- Fiyaz M, Ramesh A, Ramalingam K, Thomas B, Shetty S, Prakash P. Association of salivary calcium, phosphate, pH and flow rate on oral health: A study on 90 subjects. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:454-460.

- Kulkarni V, Bhatavadekar N, Uttamani J. The effect of nutrition on periodontal disease: a systematic review. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2014;42:302-311.

- Pushparani DS. Zinc and type 2 diabetes mellitus with periodontitis – a systematic review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2014;10:397-401.

- Tsvetkov P, Coy S, Petrova B, et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science. 2022;375:1254-1261.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. ADHA Policy Manual.Available at adha.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ADHA_Policy_Manual-FY23.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2025.

- Touger-Decker R, Mobley C. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: oral health and nutrition. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:693-701.

- Vernetti-Callahan D. Food for thought: the relationship between oral health and nutrition. Available at assets.ctfassets.net/u2qv1tdtdbbu/6tWZOOkPZkdBmK2k95PTEz/b82cbe06d433863c2b89245fffaed45d/ce583.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2025.

- Commission on Dental Accrediation. Accreditation Standards for Dental Hygiene Education Programs. Available at coda.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/coda/files/dental_hygiene_standards.pdf?rev=aa609ad18b504e9f9cc63f0b3715a5fd&hash=67CB76127017AD98CF8D62088168EA58. Accessed October 6, 2025.

- Keceli H, Ercan N, Hendek M, Ulcer K, Mesut B, Olgun E. The effect of the systemic folic acid intake as an adjunct to scaling and root planing on clinical parameters and homocysteine and C‐reactive protein levels in gingival crevicular fluid of periodontitis patients: A randomized placebo‐controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47:602-613.

- Gao W, Tang H, Wang D, Zhou X, Song Y, Wang Z. Effect of short-term vitamin D supplementation after nonsurgical periodontal treatment: A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Periodontal Res. 2020;55:354-362.

- Van Ravensteijn MM, Timmerman MF, Brouwer EAG, Slot DE. The effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on active periodontal therapy: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2022;49(:1024-1037.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November/December 2025; 23(6):28-31.