Strategies for Meeting Infection Control Protocols

In order to protect the health of patients and Oral health professionals, compliance with infection control guidelines and requirements must be a top priority.

This course was published in the August 2017 issue and expires August 2020. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss incidents of microorganism exposure and/or transmission in dental settings.

- Identify available strategies and tools to help dental offices comply with infection control guidelines.

- Define the role of the infection control coordinator.

Following best practices in infection control reduces the risk of transmission of microorganisms and disease and is integral to maintaining patient and clinician health and safety. While rare, infection control breaches do occur. Incidents of bloodborne pathogen (BBP) exposure and/or transmission have been reported over the past decade in settings such as a portable dental clinic and oral surgery and dental offices.1–3 In addition, the transmission of Legionella pneumophila via contaminated water from dental unit waterlines (DUWL) led to the death of an octogenarian due to Legionnaire’s disease.4 More recently, Mycobacterium abscessus—a fast-growing pathogen present in water, soil, and dust—was transmitted to young children undergoing pulpotomies in dental clinics in California and Georgia.5 In these cases, contaminated water from the DUWL was the source. Typically, transmission occurs through the use of contaminated equipment during invasive procedures or inoculations involving contaminated products.6 The exposure resulted in children contracting soft and hard tissue infections that required invasive surgery and intravenous antibiotic therapy over several months.5

The growing global threat posed by antibiotic resistance further emphasizes the importance of disease prevention. Antibiotic resistance has been observed in many microorganisms found in the dental setting, such as M. abscessus, M. tuberculosis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus.7–10 In addition, of the three most concerning BBPs in the dental setting—hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)—only HBV can be prevented through inoculation. Furthermore, 10% of patients newly diagnosed with HIV are infected with an anti-retroviral-resistant strain.11

Best practices for the dental setting are detailed in the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings—2003.12 The CDC also published a plain language synopsis of best practices and checklists—Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings: Basic Expectations for Safe Care—in March 2016.13 In addition, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) established mandatory standards to help protect and promote worker safety and health. The BBP Standard is particularly relevant to infection control in the dental setting, while the Hazard Communication Standard is relevant when using chemical agents as infection control products.14 Twenty-six states and two territories have their own OSHA-approved plans, which must be at least as stringent as OSHA requirements.

STRATEGIES FOR COMPLIANCE

Investigations into infection control breaches have found they were caused by the failure to properly reprocess instruments; lack of awareness, education, and training; and unsafe injection practices. These findings resulted in recommendations to improve awareness and use of standard precautions. Other reasons for infection control breaches may include human error, complacency, and, rarely, a disregard for safety. Recommended strategies to promote compliance and safety include education and training, designating an infection control coordinator, using engineering controls and work controls, and keeping immunizations up to date.12,13,15,16 Under OSHA’s BBP Standard, employers must offer the HBV vaccination at no cost to individuals at risk of BBP exposure within 10 days of hire. In one study, however, 15% of offices did not offer HBV vaccination.17 For individuals declining the HBV immunization, a signed and dated declination form must be obtained and retained in the personnel records.14 Offices and other dental facilities should have a written immunization policy.12 The increased availability of single-use devices, streamlined processes, and digital technology also helps dental professionals and staff meet requirements.

EDUCATION AND TRAINING

Compliance with infection control guidelines and procedures improves when training is provided. In one study, taking more than 6 hours of continuing education (CE) on infection control significantly improved compliance.18 Additionally, a higher percentage of participating dental hygienists reported compliance with surveyed infection control practices when working in states with mandated infection control requirements and when they had recently completed CE classes on the topic.19 Educational options include live didactic courses, hands-on workshops, journal articles, written CE courses, and internet-based training, including webinars and podcasts. Multi-modal infection-control education has been found to be more effective than more limited methods.16

The CDC guidelines recommend designating an infection control coordinator, and, by 2012, approximately 80% of offices responding to a national survey reported complying with this recommendation.16 Infection control coordinators must have the appropriate knowledge base and training. They are responsible for reviewing policies and procedures; developing written policies; managing the exposure control plan; monitoring compliance; identifying unsafe practices; noting areas for improvement; arranging or giving training to personnel in the office/facility; helping to foster a culture of safety; maintaining all relevant documents; and ensuring that disposables, equipment, and devices required for infection control are available.20,21

ENGINEERING AND WORK CONTROLS

Engineering controls must be employed, and prospective options reviewed at least annually.14 Examples include needle recapping devices, single-use disposable syringes, computerized injection systems, and self-sheathing anesthetic needles.22 Sharps safety devices are also known as engineered sharps injury protection devices. In addition, the use of sharps containers in each operatory/work area eliminates the need to transport used sharps to instrument reprocessing areas.

The risk of injury is also reduced by using instrument cassettes, ultrasonic cleaning units, instrument washers, and washer/disinfectors. Perforated, closed cassettes eliminate the need to handle instruments during cleaning. Inspection after cleaning is still required, and if areas on instruments are still visibly contaminated, further cleaning is required. Furthermore, automated cleaning is safer and more effective compared with manual cleaning.12 Instrument washers use detergents, while instrument washer/disinfectors (Figure 1) substantially reduce the bacterial load through thermal disinfection and use proprietary formulations containing detergents and chemical additives.

Work practice controls may also reduce the risk of sharps exposure. Examples include using cheek retractors instead of fingers, avoiding transferring a syringe with the needle unsheathed or pointing toward another individual, and avoiding reaching over sharp objects.

CHECKLISTS AND OBSERVATIONS

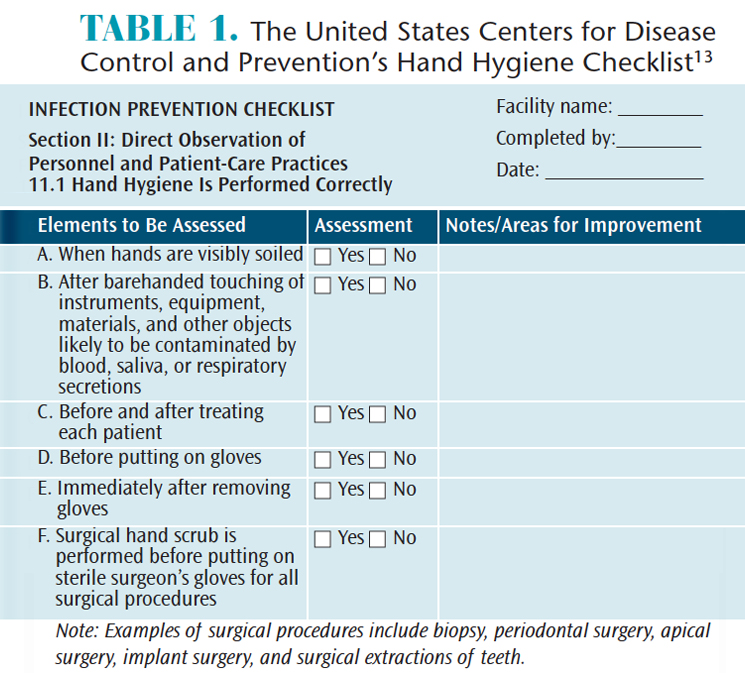

The CDC Summary contains policy and practice checklists that can be used to evaluate compliance, after which corrective action can be taken as necessary.13 The observational checklists are particularly useful when assessing compliance with repeatable infection control protocols and to help determine areas and methods for improvement. Observations include performance of individual aspects of tasks, such as hand hygiene (Table 1), donning and wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), and treatment of environmental surfaces.

Other observations can be made that may indicate further assessment is needed. For instance, if soap is lasting substantially longer than anticipated, this may mean that handrubs are being used more often, but it may also indicate that compliance with hand washing is poor. Checklists also function as reminders of critical steps and as tools for task verification. Printed and digital versions of the checklists are available at cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/index.html. The CDC DentalCheck app—compatible with the iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch—has also been introduced and is designed to help dental practices maintain compliance with infection control guidelines.23,24 Dental practices may consider conducting a self-audit, with or without the assistance of an external consultant, to seek out items that do not meet requirements.

Simplification is achieved by using single-use disposables, reducing clutter, and by barrier-protection for computers, i-Pads, and, where permissable, complex devices. Cleaning and disinfection of clinical contact surfaces can also benefit from simplification. Using a hospital-level cleaner/disinfectant means that the same product can be used for both cleaning and disinfecting. This reduces inventory requirements, simplifies tasks, and potentially reduces the risk of error. From an efficiency perspective, a significantly faster kill time for microorganisms can also decrease operatory turnaround time. In instrument reprocessing, a workflow in the instrument reprocessing area from the dirty zone receiving contaminated instruments to the clean zone with sterile instrument packs also simplifies infection control, especially if the these zones are visually indicated, such as by red lighting in the dirty zone and blue lighting in the clean zone (Figure 2).

A further consideration for effective infection control includes the selection of instruments and devices. After cleaning, in accordance with the Spaulding Classification (classification of instruments by their risk of transmitting microorganisms and disease), critical instruments/devices, as well as semi-critical heat-resistant instruments/devices and handpieces, are to be heat sterilized.12 In contrast, semi-critical heat-sensitive instruments/devices (except handpieces) are reprocessed by immersion in a high-level disinfectant/sterilant. Noncritical items are treated using US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered disinfectants. An intermediate-level disinfectant must be used if visible blood is present; if no visible blood is present, a low-level disinfectant may be utilized.12When determining which instrument/device to purchase, consider the reprocessing instructions and whether they are compatible with the reprocessing requirements based on the Spaulding Classification. Another consideration is the complexity of a device (eg, whether it must be disassembled prior to reprocessing and whether individual parts need to be reprocessed differently).

Products regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) include high-level disinfectant/sterilants and sterilization pouches, ultrasonic cleaners, instrument washers, washer/disinfectors, and autoclaves.25 These medical devices have undergone review by the FDA, as have the manufacturer’s instructions for use, unlike products that are similar but not medical devices. For example, a dishwasher has not been assessed for safety and efficacy for use as infection control equipment in the dental setting. Using a dishwasher does not represent the standard of care, and has been shown to be ineffective for instrument cleaning.26 Instrument washer/disinfectors, in contrast, are highly effective.27 Similarly, the EPA regulates hospital-level (low- and intermediate-level) disinfectants. One way to determine if the product is EPA-registered is to look for the EPA registration number on the product labeling.

Products must be readily available and accessible, and personal needs and preferences should be considered. One potential issue is frequent hand washing, which can irritate hands—particularly if they are not dried properly—and impact compliance. When hands are not visibly soiled, using 60% to 95% alcohol-based handrubs for routine hand hygiene may aid compliance, as they are less drying on hands than soap and water.28 In addition, soaps and alcohol-based handrubs containing emollients can increase hand hygiene compliance by helping to maintain epidermal water content and improve skin health.29 Emollient lotions assist in maintaining skin health. Barrier creams may also be helpful.

Compliance may be an issue with PPE, which includes clinical attire; surgical face masks (or respirator for transmission-based precautions);30 single-use medical or sterile surgical gloves for patient care; utility gloves for operatory clean-up and instrument reprocessing; and protective eyewear. The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) has standards for rating masks based on bacterial and particulate filtration efficacy, fluid resistance, breathability, and flame resistance. Using an ASTM-rated mask ensures the wearer knows its level of protection, which is not the case with unrated masks. ASTM 3-rated surgical face masks provide the highest level of protection. However these masks are also typically thicker and less breathable than ASTM-1 or ASTM-2 rated masks, and they are generally used in situations in which greater protection is required. Compliance with mask-wearing may be better if the mask feels comfortable and soft, and is breathable. Research on wearing N95 respirators showed that discomfort, heat build-up, and low breathability negatively impact compliance.31

Glove fit and comfort affect compliance, and gloves should be available in several sizes. Right- and left-handed gloves may be more comfortable than ambidextrous gloves. In addition, OSHA requires that an employer ensure that hypoallergenic gloves, glove liners, or something similar are available for workers. This helps to encourage glove use by individuals with allergies/sensitivity to glove materials. As PPE is worn throughout the day, comfort and preference are important considerations. Displaying a chart with images of the recommended sequence of donning and doffing PPE in the operatory and instrument reprocessing area can also remind oral health professionals on the protocol and, thereby, aid compliance.

DIGITAL TOOLS

In addition to the CDC checklists and DentalCheck, a variety of digital tools to aid compliance is available. These include but are not limited to phone and tablet apps, interactive website support from product manufacturers, pre-scheduled collection of regulated waste and inventory replenishment, cell phone-generated reminders to perform a task (eg, spore testing), and digital archiving of autoclave cycles and automated instrument cleaning. Measurement tools are available to assess the safety culture in a dental setting,32 for example the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Survey, which can be found online.33

Ultimately, effective infection control requires that the relevant guidelines and regulations are followed. Competency and compliance with infection control benefit patients, oral health professionals, and society at large.

REFERENCES

- Radcliffe RA, Bixler D, Moorman A, Cleveland JL. Hepatitis B virus transmissions associated with a portable dental clinic, West Virginia, 2009. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144(10):1110–1118;

- Oklahoma Department of Health. Dental Healthcare-Associated Transmission of Hepatitis C. Final Report of Public Health Investigation and Response, 2013. Available at: ok.gov/health2/documents/Dental%20Healthcare_Final%20Report_2_17_15.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Urciuoli A. Burlington dental patients told to get tested for hepatitis and HIV. Available at: globalnews.ca/news/3544446/burlington-dental-patients-told-to-get-tested-for-hepatitis-and-hiv/. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Ricci ML, Fontana S, Pinci F. Pneumonia associated with a dental unit waterline. Lancet. 2012;379:684.

- American Dental Association. Nontuberculosis mycobacterial infection linked to pulpotomy procedures and possible dental waterline contamination reported in California and Georgia. September 21, 2016. Available at: ada.org/en/science-research/science-in-the-news/nontuberculosis-mycobacterial-infection-linked-to-pulpotomy-procedures. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare-associated Infections. Mycobacterium abscessus in Healthcare Settings. Available at: cdc.gov/hai/organisms/mycobacterium.html. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Nessar R, Cambau E, Reyrat JM, Murray A, Gicquel B. Mycobacterium abscessus: a new antibiotic nightmare. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:810–818.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare-Associated Infections. Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Available at: cdc.gov/tb/publications/ factsheets/drtb/mdrtb.htm. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare-Associated Infections. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in Healthcare Settings. Available at: cdc.gov/hai/organisms/pseudomonas.htm. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Kurita H, Kurashina K, Honda T. Nosocomial transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus via the surfaces of the dental operatory. Br Dent J. 2006;201:297–300.

- World Health Organization. WHO Urges Action Against HIV Drug Resistance Threat. Available at: who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2017/hiv-drug-resistance/en/. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings—2003. Available at: cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5217al.htm. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings: Basic Expectations for Safe Care. March, 2016. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/pdf/safe-care.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Medical & Dental Offices. A Guide to Compliance with OSHA Standards. Available at: www.osha.gov. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Cleveland JL, Gray SK, Harte JA, Robison VA, Moorman AC, Gooch BF. Transmission of blood-borne pathogens in US dental health care settings: 2016 update. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147:729–-738.

- Cleveland JL, Bonito AJ, Corley TJ, et al. Advancing infection control in dental care settings: Factors associated with dentists’ implementation of guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143:1127–1138.

- Laramie AK, Bednarsh HS, Isman B, et al. Use of bloodborne pathogens exposure plans in private dental practices: results and clinical implications of national survey. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2016;38(6):398–407.

- McCarthy GM, Koval JJ, MacDonald JK. Compliance with recommended infection control procedures among Canadian dentists: results of a national survey. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27:377–384.

- Kelsch N, Davis CA, Essex G, Laughter L, Rowe DJ. Effects of mandatory continuing education related to infection control on the infection control practices of dental hygienists. Am J Infect Control. March 17, 2017. Epub ahead of print.

- Palenik CJ, Miller CH. Creating the position of office safety coordinator. Dent Assist. 2002;71:10–-14.

- Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention. Team Huddle Defining the role of the infection control coordinator: Part 2. Infection Control in Practice. 2015;14(3):1–4.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Quick Reference Guide to the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. Available at: www.osha.gov/SLTC/bloodbornepathogens/bloodborne_quickref.html. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DentalCheck. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/dentalcheck.html. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Flodgren G, Hall AM, Goulding L, et al. Tools developed and disseminated by guideline producers to promote the uptake of their guidelines. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;8:CD010669.

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA Basics. Available at: fda.gov/AboutFDA/Transparency/Basics/ucm194879.htm. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- O’Connor H, Armstrong N. An evaluation of washer-disinfectors (WD) and dishwashers (DW) effectiveness in terms of processing dental instruments. J Ir Dent Assoc. 2014;60:84–89.

- Rutala WA, Gergen MF, Weber DJ. Efficacy of a washer-disinfector in eliminating healthcare-associated pathogens from surgical instruments. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:883–885.

- Boyce JM, Kelliher S, Vallande N. Skin irritation and dryness associated with two hand-hygiene regimens: soap-and-water hand washing versus hand antisepsis with an alcoholic hand gel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:442–448.

- Boyce JM, Pittet D; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee; HICPAC/SHEA/ APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care Settings. Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Association for Professionals in Infection Control/Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-16):1–45,

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings. Available at: cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/isolation/Isolation2007.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2017.

- Baig AS, Knapp C, Eagan AE, Lewis RN, Radonovich LJ. Health care workers’ views about respirator use and features that should be included in the next generation of respirators. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38:18–25.

- Sorra JS, Nieva VF. Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. AHRQ Publication No. 04-0041.Rockville, Maryland: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004.

- The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Stop Sticks Campaign. Safety Culture: Evaluation Survey. Available at: cdc.gov/niosh/stopsticks/survey.html. Accessed July 28, 2017.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2017;15(8):59-62.