Improving Access to Care

Dental hygienists play an important role in helping disadvantaged populations receive the oral health care they need.

This course was published in the September 2014 issue and September 30, 2017. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define underserved or vulnerable populations.

- Identify barriers to care encountered by underserved populations.

- Discuss the various models being implemented to improve access to care at the state level.

- Explain the role of dental hygienists in improving the oral health of the underserved.

BARRIERS TO ACCESSING CARE

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines racial or ethnic minorities, people with special health care needs, older adults, pregnant women, populations of lower socioeconomic status, and rural populations as those who are underserved.2 Although many Americans receive oral health care through third-party payer insurance systems in traditional dental practices, about one-third face barriers to accessing or seeking oral health care services.3 These barriers include: cultural differences, geographic challenges, and financial issues.

Cultural differences may interfere with the provision of dental care because certain groups emphasize traditional healing methods and exhibit distrust of Western medicine.4 Patients may doubt the competency of providers who are of a different culture than their own, or may have difficulty communicating with providers.

The geographic location of dental practices may also prevent individuals from accessing care.4 Many dentists graduate with heavy student loan debt, which discourages them from starting practices in rural or low socioeconomic areas where reimbursement rates may be low. As such, many dental offices are located in affluent areas, which can create transportation issues for individuals who live outside of these communities.

The greatest barriers to receiving oral health care are financial.4 The cost of operating a private dental practice is very high, making the treatment of patients who are uninsured, need discounted rates, and rely on public insurance plans undesirable. For patients who cannot afford to pay out-of-pocket for dental care, the cost of professional oral health care services is prohibitive. Also, dental services are often not covered through state public insurance plans. For individuals who earn an hourly wage without paid sick or vacation benefits, the loss of earnings that results when they take time off to receive dental care presents a significant barrier.

SOLUTIONS TO THE ACCESS-TO-CARE PROBLEM

Several organizations have convened to develop solutions to the access to oral health care issue in the United States. In 2003, the Alaskan Native Health Consortium, with the support of tribal health organizations, initiated the dental health aide therapist (DHAT) program to increase oral health care to rural villages in Alaska.5 The DHAT program was modeled after the New Zealand dental therapist program, which began in 1921, and has proven successful in alleviating some of the country’s access to oral health care issues.6 Research has shown that dental therapists in New Zealand provide quality, cost-effective care.6

In 2008, an effort to develop a mid-level oral health practitioner in Minnesota began that was modeled after the advanced dental hygiene practitioner (ADHP) proposed by the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA).7 The governor of Minnesota signed the dental therapist (DT) legislation into law in 2009. Both Metropolitan State University in St. Paul, in partnership with Normandale Community College, and the University of Minnesota, School of Dentistry in Minneapolis, implemented programs that same year.8 Currently, Minnesota has two levels of dental therapy: the DT and the advanced dental therapist (ADT).8 The DT requires a baccalaureate- or master’s-level degree from the University of Minnesota.9 The Metropolitan State University master’s degree combines the DT and ADT into one program.10 Applicants to the master’s degree program must hold a baccalaureate degree and current dental hygiene license.10 The DT can provide basic preventive services, limited restorative care, and extraction of primary teeth.8,11 All restorative care requires the direct supervision of a dentist on-site.8,11 The ADT may perform all services under the general supervision of a dentist and within the parameters of a collaborative agreement between the ADT and the dentist.8,11

In April 2014, the governor of Maine signed the dental hygiene therapy bill into law.12 This new legislation enables dental hygiene therapists to perform both preventive and restorative care under the supervision of a dentist, and in specified settings, such as hospitals, public schools, clinics, or federally qualified health centers in Maine.12 Several other states are pursuing legislation to establish dental therapist providers to increase access to oral health care, including Washington, Oregon, Kansas, New Mexico, and Vermont.13

In response to cases like that of 12-year-old Deamonte Driver—who died due to an untreated tooth infection—the Health Resources and Services Administration and the California HealthCare Foundation asked the IOM and the National Research Council to further investigate the access to oral health care issue.2,14,15 In 2009, the IOM?hosted a 3-day workshop titled “Sufficiency of the United States Oral Health Workforce in the Coming Decade.”14,15 The panel of oral health and research experts discussed the issues that led to oral health disparities, various workforce models that may alleviate such problems, and strategies for encouraging policy makers to become involved in improving oral health care.14 The committee provided many recommendations, including expanding the purview of a variety of providers who are competent to provide oral health care, as well as changing practice act laws to allow professionals to practice to the full magnitude of their education and in alternative settings.2,14 The committee members considered several workforce strategies to address the access to oral health care issue, including how various dental professionals—such as community dental health coordinators, dental health aide therapists, and dental hygienists in alternative practice settings—could assist in increasing care, especially in areas with provider shortages.15

DIRECT ACCESS STATES

In response to developing and expanding the dental workforce in the United States, several states have created new models, in addition to the dental therapist, that enable a greater number of dental hygienists to provide care to underserved populations with little to no supervision by a dentist. The ADHA refers to states that allow dental hygienists to practice in alternative settings as direct access states.16 ADHA defines these states as those where “the dental hygienist can initiate treatment based on his or her assessment of patient’s needs without the specific authorization of a dentist, treat the patient without the presence of a dentist, and can maintain a provider-patient relationship.”16 There are currently 37 direct access states. The ADHA provides a comprehensive look at the different types of direct access used in different states at: adha.org/resources-docs/7513_Direct_Access_to_Care_from_DH.pdf. Dental hygienists who want to pursue direct access licenses should check with their state dental board for specific requirements.

ALTERNATIVE PRACTICE MODELS

California’s registered dental hygienist in alternative practice (RDHAP) model has been successful in increasing access in areas experiencing shortages of dental professionals. The RDHAP program began with the Health Manpower Pilot Project study in 1980 and took 23 years to become fully implemented.17 The Health Manpower Pilot Project expanded roles in health care through formal education and clinical training, along with the demonstration of safe and effective care provided to the public.18 At the conclusion of the study, the Health Manpower Pilot Project found that dental hygienists who work in independent practice charged fees that were more affordable for individuals without insurance, were more available to patients with public insurance, referred patients to dentists for additional care, and demonstrated safe and satisfactory care to the public.18

California’s registered dental hygienist in alternative practice (RDHAP) model has been successful in increasing access in areas experiencing shortages of dental professionals. The RDHAP program began with the Health Manpower Pilot Project study in 1980 and took 23 years to become fully implemented.17 The Health Manpower Pilot Project expanded roles in health care through formal education and clinical training, along with the demonstration of safe and effective care provided to the public.18 At the conclusion of the study, the Health Manpower Pilot Project found that dental hygienists who work in independent practice charged fees that were more affordable for individuals without insurance, were more available to patients with public insurance, referred patients to dentists for additional care, and demonstrated safe and satisfactory care to the public.18

Currently, there are two RDHAP programs in California: West Los Angeles College in Culver City and University of the Pacific in Stockton.19,20 The requirements to apply for the RDHAP program include a baccalaureate degree or equivalent; maintaining an active California registered dental hygienist license; engaging in clinical dental hygiene practice for 2,000 hours during the 36 months preceding the application; completing 150 hours of the RDHAP educational program; and successfully passing a written California law and ethics exam.19,20

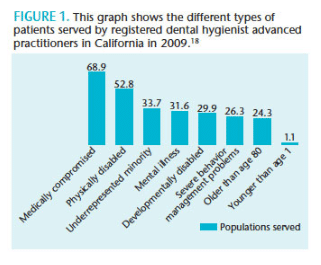

RDHAPs can provide care to patients who live in dental health professional shortage areas, such as schools, residences of homebound patients, and long-term care facilities.18 A study in 2005/2006 and 2009 compared practice differences between RDHs and RDHAPs.18 Results showed that RDHAPs were increasing access to care, especially among minority populations, as well as patients with disabilities and special needs.18 Figure 1 shows the types of populations that the RDHAPs served in 2009.18

REIMBURSEMENT

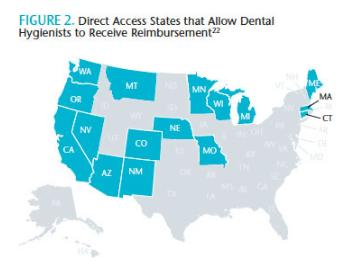

Although several direct access states allow dental hygienists to practice in alternative settings, the reimbursement mechanisms are complicated. Only 16 states allow dental hygienists to serve as Medicaid providers.21 This is a barrier to fully utilizing dental hygienists in alternative provider models. The ADHA website outlines the steps necessary for dental hygienists to become Medicaid providers in the direct access states that allow dental hygienists to be reimbursed for services (Figure 2).21 These include obtaining a national provider identifier number from the federal government, and using the codes listed in the current dental terminology code book.21

THE EVOLUTION OF THE DENTAL HYGIENE PROFESSION

Emerging models, such as those created in states that allow dental hygienists to provide direct access, are an important part of increasing access to care. Dental hygienists need to continue to evolve the scope of practice laws and supervision requirements in their states, and practice in these emerging models to increase oral health care access among underserved populations. Dental hygienists need to explore other innovative settings that could benefit from the preventive services and oral health education dental hygienists provide. Settings such as Women, Infants, and Children facilities or pediatric offices where dental hygienists could educate new parents about the oral health of their babies and how to prevent oral disease should be considered. In addition, dental hygienists can provide screening and apply fluoride varnish to children who visit their pediatricians. Head Start programs are the perfect sites for instituting fluoride varnish programs and educating staff and parents about oral health. Schools provide an ideal setting for dental sealant and fluoride varnish programs, along with oral health education programs. To support older adults, long-term care facilities are optimal settings for providing oral health care and education along with oral cancer screenings and educating the nursing staff about the importance of good oral health. Dental hygienists could also work in home health programs to provide oral health care to patients who have difficulty traveling to traditional dental offices and to educate caregivers about oral health.

The development of so many emerging workforce models and alternative settings makes this an exciting time for the dental hygiene profession. Dental hygienists must continue to evolve the profession and advocate for underserved populations. While practicing in an alternative setting or fulfilling a role in one of the workforce models is outside of the traditional practice box, this type of expansion can inspire dental hygienists to grow both personally and professionally. The opportunities are endless for dental hygienists who wish to increase care to underserved populations.

REFERENCES

- Satcher DS. Surgeon General’s report on oral health. Public Health Rep. 2000;115:489–490.

- Institute of Medicine. Improving Access To Oral Health Care For Vulnerable And Underserved Populations. Available at: iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2011/Improving-Access-to-Oral-Health-Care-for-Vulnerable-and-Underserved-Populations/oralhealthaccess2011reportbrief.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- American Dental Association. Access to Care. Available at: ada.org/en/public-programs/action-for-dental-health/access-to-care. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- Mason J. Access to oral health care. In: Sabatini, P, ed. Concepts in Dental Public Health. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2010:31–39.

- Wetterhall S, Bader JD, Burrus BB, Lee JY, Shugars DA. Evaluation of the dental health aide therapist workforce model in Alaska. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:322–326.

- The PEW Charitable Trusts. Dental Therapists In New Zealand: What The Evidence Shows. Available at: pewtrusts.org/~/media/Imported-and-Legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2013/PewNewZealanddentalbriefpdf.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. The History of Introducing a New Provider in Minnesota. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/75113_Minnesota_Story.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- Blue CM, Lopez N. Towards building the oral health care workforce: who are the new dental therapists? J Dent Educ. 2011;75:36–45.

- University of Minnesota. Dental Therapy—A New Profession. Available at: dentistry.umn. edu/ programs-admissions/dental-therapy/index.htm. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- Metropolitan State University. Advanced Dental Therapy Program. Available at: metrostate.edu/msweb/explore/gradstudies/masters/msadt. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- Minnesota Board of Dentistry. Scope of Practice for Dental Therapists and Advanced Dental Therapists. Available at: dentalboard.state.mn.us/Default.aspx?tabid=1165. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- American Dental Education Association. Governor of Maine Signs Dental Hygiene Therapy Bill into Law. Available at: adea.org/Blog.aspx?id=23932&blogid=20132. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. American Dental Hygienists’ Association Supports Increased Access of Dental Hygienists and Mid-Level Providers to Help Deliver Dental Services. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/ADHA_Supports_Increased_Access_to_Care_Use_of_Dental_Hygienists_and_Mid_level_Providers.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- Mertz EA, Finocchio L. Improving oral healthcare delivery systems through workforce innovations: an introduction. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70:S1-S5.

- Institute of Medicine. The US Oral Health Workforce in the Coming Decade: Summary of a Workshop. Available at: iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2009/OralHealthWorkforce/Oral%20Health%20Workforce%202009%20%20Workshop%20Highlights.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Direct Access States. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/7513_Direct_Access_to_Care_from_DH.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- Mertz E. Registered Dental Hygienists in Alternative Practice: Increasing Access to Dental Care in California—an Executive Summary. Available at: sfdda.org/web/pdf/ga/RDHAP_Executive_Summary_2008.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- Mertz E, Glassman P. Alternative practice dental hygiene in California: past, present, and future. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2011;39:37–46.

- West Los Angeles College. Registered Dental Hygienist in Alternative Practice Program. Available at: wlac.edu/alliedhealth/CE.html#RDHAP%20Oveview. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- University of the Pacific. Registered Dental Hygienist in Alternative Practice Educational Course. Available at: dental.pacific.edu/Community_Involvement/Pacific_Center_for_Special_Care_%28PCSC%29/Education_/RDHAP_Online_Curriculum.html. Accessed August 19, 2014.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Dental Hygiene: Reimbursement Pathways. Available at: adha.org/resourcesdocs/7529_Report_Reimbursement_Pathways.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2014.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2014;12(9):75–78.