ADVENTTR/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

ADVENTTR/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

A Comprehensive Approach to Dental Caries Management

Risk assessment, therapeutic and restorative therapies, establishment of a dental home, and interprofessional care are key to mitigating the negative effects of tooth decay.

This course was published in the April 2017 issue and expires April 2020. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define early childhood caries and its etiology.

- Discuss the role of risk assessment in caries prevention and management.

- Identify the importance of establishing a dental home in promoting oral health.

- Explain appropriate therapeutic and restorative approaches for caries management.

- Outline the role of medical providers in identifying caries risk in pediatric patients.

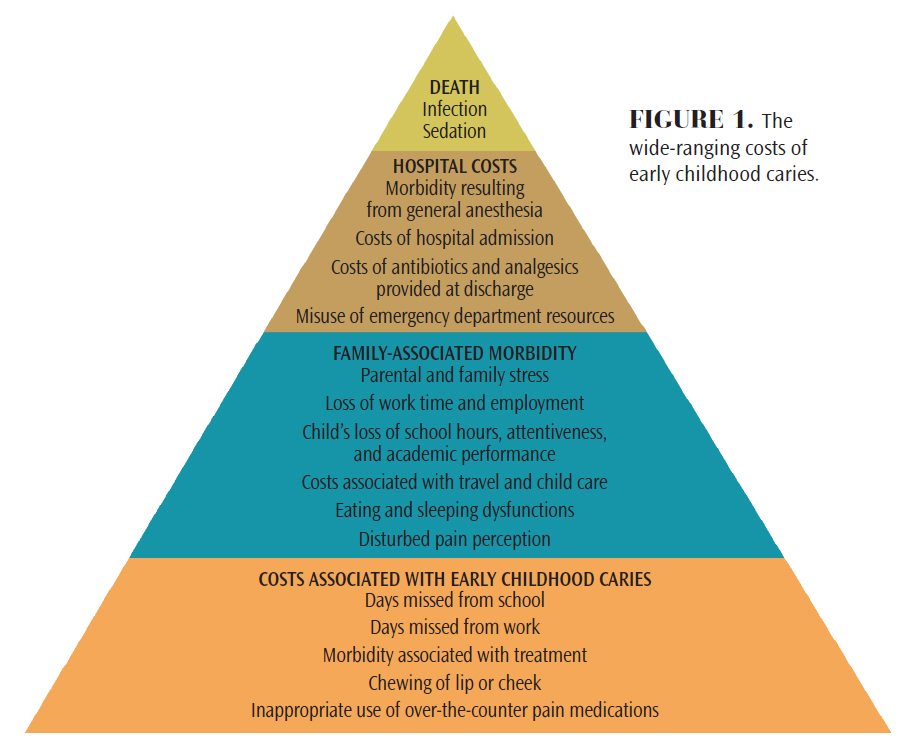

Dental caries remains a national and global public health epidemic, affecting both children and adults from all races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic levels.1–3 The signs and symptoms associated with caries include pain and infection from active lesions, nutritional deficiencies, learning and speech problems, and, rarely, death (Figure 1).2–5 Among children in the United States, caries is the most common unmet health need, with a prevalence of more than 25% among children age 24 months to 60 months.3

Caries is typically caused by disruptions in the balance between cariogenic bacteria and host factors, such as enamel susceptibility, salivary flow, and composition.2,6 Family culture and economic and social status also substantially impact caries development.2,6Current research demonstrates that multiple risk factors are responsible for dental caries, including frequent sugar consumption, improper/lack of oral hygiene, high levels of oral bacteria, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and inconsistent access to oral health care.2,5,7–11

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) defines early childhood caries (ECC) as the presence of one or more decayed (noncavitated or cavitated lesions), missing (due to caries), or filled tooth surfaces (dmft) in any primary tooth in a child age 71 months or younger.12 In children younger than 36 months, any sign of smooth-surface caries is indicative of severe early childhood caries (S-ECC).12 Children aged 36 months to 60 months who have one or more cavitated teeth, missing (due to caries), or filled smooth surfaces in primary maxillary anterior teeth, or a decayed, missing or filled score of ≥4 (36 months), ≥5 (48 months), or ≥6 (60 months) surfaces have S-ECC.12

Children between the ages of 12 months and 30 months have a unique pattern of caries development that differs from older children.7 ECC within this age group is distinguished by lesions found on the maxillary primary incisors and first primary molars, reflecting the pattern of eruption.1,2,4,13

CARIES ETIOLOGY

Caries occurs when cariogenic bacteria colonize a susceptible tooth surface in the presence of carbohydrates.14 While more than 800 species of bacteria have been found in dental plaque,15–17 the four primary oral bacteria associated with dental caries are Streptococcus mutans, Lactobacilli, Streptococcus sobrinus, and Bifidobacteria.18

Enamel is composed of a matrix of hydroxyapatite crystals and protein, with inorganic components accounting for 96% of its structure.19 When carbohydrates and fermentable sugars are ingested, the pH of the oral cavity decreases, dropping from a neutral pH of 7.0 to an acidic pH of approximately 5.0 to 5.5.19 This increased acidity is also found within the biofilm fluid. If cariogenic bacteria are already present, the carbohydrates and fermentable sugars are metabolized by this acid-producing bacteria.19 If the quantity of bacteria is high due to inadequate oral hygiene practices, acid production is increased.19

The acid that is produced at the biofilm level diffuses into the enamel, causing structural demineralization.19 However, the enamel can remineralize once the carbohydrate exposure has ended.19 These cycles of demineralization/remineralization continue as long as cariogenic bacteria, fermentable carbohydrates, and saliva are present within the oral cavity. If this cycle occurs frequently, the demineralization eventually surpasses saliva’s remineralizing abilities, creating initial white-spot or incipient lesions that may progress to cavitation.14,19,20 A child’s risk of developing caries lesions is influenced by many factors and can change over time.14 Dietary patterns of carbohydrate consumption and other genetic, personal, and social factors—such as oral hygiene habits, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity—all affect caries development.2,6,7,20

RISK ASSESSMENT

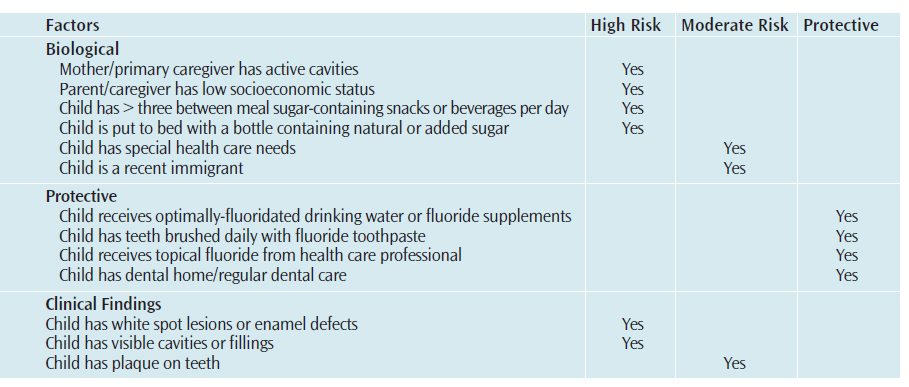

Identifying a child’s caries risk is an effective and evidence-based approach to disease prevention and management. Caries management by risk assessment (CAMBRA) enables oral health professionals to recommend patient-tailored therapeutic, restorative, oral hygiene, educational, and nutritional approaches for pediatric patients and their parents/caregivers.21 This chairside assessment measures each child’s disease indicators, risk factors, and protective factors, which help oral health professionals determine current and future dental caries disease status and risk.21

Through risk assessment, oral health professionals can identify cariogenic feeding patterns, assess the child’s use of fluoride toothpaste or frequency of fluoride varnish applications, and communicate to parents/caregivers the presence of active caries lesions or dental plaque. This evaluation can be performed during any routine dental prophylaxis and examination.

ESTABLISH A DENTAL HOME

The AAPD defines a dental home as, “the ongoing relationship between the dentist and the patient, inclusive of all aspects of oral health care delivered in a comprehensive, continuously accessible, coordinated, and family-centered way. The dental home should be established no later than 12 months and includes referral to specialists when appropriate.”22 An anticipatory approach emphasizing oral health promotion through guidance and parental/caregiver education is likely to have the greatest impact on children’s oral health.3,23 Preventive care visits can be used to reinforce the necessity and importance of maintaining routine dental examinations and prophylaxes, as well as to educate parents/caregivers on proper oral hygiene techniques and behavioral and social risk factors.8Nutritional education should be provided during preventive care visits in order to ensure cariogenic feeding practices are avoided and proper dietary guidelines are followed for optimal oral and overall heath.

The goal of providing anticipatory guidance for parents/caregivers is to modify or eliminate practices and behaviors known to increase caries risk.3,24 According to the AAPD, care within a dental home should include: comprehensive assessment; individualized preventive care based on caries risk; anticipatory guidance related to growth and development, including care of the child’s soft and hard tissues; education of parents/caregivers on management of acute dental trauma; nutritional assessment and counseling; and referral to specialists, if needed.22

One recent cross-sectional study explored the association of an established dental home on ECC prevalence and cariogenic feeding practices in high-risk populations.24 The dental caries disease status (dmft score), incidence of plaque biofilm and gingivitis, and the practice of high-risk dietary behaviors were compared among two groups of children age 24 months to 60 months, differentiated by the presence of an established dental home. The results of this study demonstrated significant relationships between higher dmft scores and a frequent consumption of sticky snacks (candy) and sugary drinks (juice), as well as prolonged drinking sessions of sugary beverages.24 Children with an established dental home had a lower prevalence of caries and lower rates of biofilm and gingivitis than children who did not have an established dental home. These findings add further evidence to support the effectiveness of oral hygiene education and anticipatory guidance in the prevention of adverse oral health outcomes.24

On the other hand, a recent study examining early prevention in the reduction of dental caries among Medicaid-enrolled children did not find any benefits.25 Results showed that children who received preventive dental care before age 2 were more likely to need treatment for dental caries over several years. However, the study had significant limitations, including the use of claims data that did not consider quality of life improvement. Another was the lack of accounting for oral health behaviors that may have contributed to the increased need for follow-up dental care. Furthermore, this study was conducted in one state, limiting its relevance nationwide. Lastly, the investigators were not able to account for community water fluoridation, which may have impacted caries rates.25 Reasons as to why the study found no beneficial evidence to early prevention in caries reduction may be that more children sought early care simply because they had a dental home. In contrast, the rate of undiagnosed and untreated caries in children who did not receive early preventive care may be high. According to the Alabama Department of Public Health, approximately 20% of Alabama’s children aged 6 to 9 have untreated dental caries.26

THERAPEUTIC AND RESTORATIVE APPROACHES

Protective modalities, specifically topical fluoride, should be employed to inhibit demineralization, promote remineralization, and obstruct the formation of cariogenic plaque especially among high-risk patients. The AAPD recommends that all children use fluoride toothpaste twice daily, regardless of caries risk.27 For children age 36 months and younger, no more than a “smear or rice-sized” amount should be used. For children between the ages of 36 months and 60 months, a “pea-size” amount is indicated. Using more than the recommended amount can increase the risk of fluorosis.27 The frequency of fluoride varnish (5% NaF) application is determined by the child’s caries risk. Application intervals for pediatric patients at high-caries risk are typically every 3 months to 6 months.

Multiple factors should be considered when determining restorative treatment for pediatric patients with ECC. Clinicians need to consider the child’s age and future caries risk, engagement of parents/caregivers, and severity of the lesions to determine an evidence-based course of action.28–32 Some children may be placed on “active surveillance,” a nonsurgical approach in which oral health professionals carefully monitor the progression of certain lesions through a specific plan of follow-up and behavior change. This approach includes active parental engagement, frequent recare appointments with fluoride varnish applications, and consistent self-care measures, including brushing with fluoride toothpaste and improving dietary behaviors.30–32

If a pediatric patient requires restorative treatment, permanent restorations or interim therapeutic restorations—such as glass ionomer or resin-modified glass ionomer cement—can be considered.28 Silver diamine fluoride (38% w/v Ag(NH3)2F, 30% w/w) is a topical agent composed of 24.4% to 28.8% (w/v) silver and 5.0% to 5.9% fluoride that has been shown to arrest caries and can be used to address caries lesions in primary teeth.33–35 In 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration cleared a silver diamine fluoride product for market and gave it a breakthrough designation in 2016 for arresting caries in children and adults.

INTERPROFESSIONAL CARE

The role of pediatricians and allied medical providers in children’s oral health continues to grow as the mouth-body connection becomes better understood. Schools such as New York University’s Rory Meyers College of Nursing have created programs like the Oral Health Nursing Education and Practice Program to incorporate oral-systemic health content, as well as clinical competencies into nurse practitioner curricula. Nurse practitioners in pediatric settings have more frequent access to new mothers and infants than oral health professionals. Improved oral health training can help them better and more efficiently recognize oral disease and identify high-risk cariogenic behavior.36–38 According to the Medical Expenditure Survey, 89% of children younger than age 1 had routine physician visits annually, while only 1.5% of these children had dental visits.37 Another study indicated that 99% of Medicaid-enrolled children had well-baby visits before age 1, compared with only 2% who had a dental visit.36 Therefore, medical professionals need to incorporate oral health assessments into their preventive appointments (Table 1) to reinforce oral health-promoting behaviors, apply fluoride varnish, and facilitate the establishment of a dental home.36–38 The majority of states reimburse nondental professionals for caries-prevention services performed during the medical appointment.39

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that the first oral health risk assessment be performed by 6 months and continue at 9 months, 18 months, 24 months, 30 months, 3 years, and 6 years.40 The objective of performing caries risk assessment in the medical home is to prevent disease by identifying and decreasing contributory factors while optimizing protective factors, specifically fluoride exposure, proper oral hygiene, and sealants.29,38,41 Risk assessment also enables medical providers to identify high-risk patients and refer them to an oral health care provider.

Oral health is essential to general health. As family, economic, and social statuses significantly impact the development of ECC, emphasizing oral health-promoting behaviors is likely to have the greatest effect on children’s oral health.6,42,43 Oral health professionals, as well as medical providers play critical roles in identifying high-risk behaviors and providing patient-specific education and counseling to improve outcomes. For high-risk pediatric patients, educating parents/caregivers on the known risk factors associated with ECC is imperative.5,6,8–11

REFERENCES

- Arora A, Scott JA, Bhole S, et al. Early childhood feeding practices and dental caries in preschool children: A multi-centre birth cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:28.

- Kawashita Y, Kitamura M, Saito T. Early childhood caries. Int J Dent. 2011;2011:725320.

- Nunn ME, Dietrich T, Singh HK, et al. Prevalence of early childhood caries among very young urban boston children compared with US children. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69:156–162.

- Bugis BA. Early childhood caries and the impact of current US medicaid program: An overview. Int J Dent. 2012;2012:348237.

- Kagihara LE, Niederhauser VP, Stark M. Assessment, management, and prevention of early childhood caries. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21:1-10.

- Harrison R. Oral health promotion for high-risk children: Case studies from british columbia. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:292–296.

- Nunn ME, Braunstein NS, Krall Kaye EA, et al. Healthy eating index is a predictor of early childhood caries. J Dent Res. 2009;88:361–366.

- Mobley C, Marshall TA, Milgrom P, et al. The contribution of dietary factors to dental caries and disparities in caries. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:410–414.

- Palmer CA, Kent R,Jr, Loo CY, et al. Diet and caries-associated bacteria in severe early childhood caries. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1224–1229.

- Warren JJ, Weber-Gasparoni K, Marshall TA, et al. A longitudinal study of dental caries risk among very young low SES children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:116–122.

- Prakash P, Subramaniam P, Durgesh BH, et al. Prevalence of early childhood caries and associated risk factors in preschool children of urban bangalore, india: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Dent. 2012;6:141–152.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Definition of Early Childhood Caries. Available at: aapd.org/ assets/1/7/D_ECC.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2017.

- Losso EM, Tavares MC, Silva JY, et al. Severe early childhood caries: An integral approach. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2009;85:295–300.

- Caufield PW, Li Y, Dasanayake A. Dental caries: An infectious and transmissible disease. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2005;26(Suppl 1):10–16.

- Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, et al. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5721–5732.

- Paster BJ, Boches SK, Galvin JL, et al. Bacterial diversity in human subgingival plaque. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3770–3783.

- Preza D, Olsen I, Aas JA, et al. Bacterial profiles of root caries in elderly patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2015–2021.

- Mantzourani M, Gilbert SC, Sulong HN, et al. The isolation of bifidobacteria from occlusal carious lesions in children and adults. Caries Res. 2009;43:308–313.

- Garcia-Godoy F, Hicks MJ. Maintaining the integrity of the enamel surface: The role of dental biofilm, saliva and preventive agents in enamel demineralization and remineralization. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;13(9 Suppl): 25S–34S.

- Filoche S, Wong L, Sissons CH. Oral biofilms: Emerging concepts in microbial ecology. J Dent Res. 2010;89:8–18.

- Featherstone JD, Domejean-Orliaguet S, Jenson L, et al. Caries risk assessment in practice for age 6 through adult. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:703–713.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Definition of a Dental Home. Available at: aapd.org/media/ policies_guidelines/p_dentalhome.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2017.

- Edelstein B, Vargas CM, Candelaria D, et al. Experience and policy implications of children presenting with dental emergencies to US pediatric dentistry training programs. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:431–437.

- Kierce EA, Boyd LD, Rainchuso L, et al. Association between early childhood caries, feeding practices and an established dental home. J Dent Hyg. 2016;90:18–27.

- Blackburn J, Morrisey MA, Sen B. Outcomes associated with early preventive dental care among Medicaid-enrolled children in Alabama. JAMA Pediatr. February 27, 2017. Epub ahead of print.

- Alabama Department of Public Health. The Oral Health of Alabama’s Kindergarten and Third Grade Children Compared to the General U.S. Population and Healthy People 2020 Targets. Available at: adph.org/ oralhealth/assets/Data%20Brief%20Alabama%202011-2013.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2017.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Fluoride Therapy. Available at: aapd.org/media/ Policies_Guidelines/G_fluoridetherapy.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2017.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Interim Therapeutic Restorations. Available at: aapd.org/media/policies_guidelines/p_itr.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2017.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Caries-Risk Assessment and Management for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Available at: aapd.org/ media/policies_guidelines/g_cariesriskassessment.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2017.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Early Childhood Caries. Available at: aapd.org/media/ policies_guidelines/p_eccuniquechallenges.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2017.

- Arrow P KE. Minimum intervention dentistry approach to managing early childhood caries: A randomized control trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015;43:511–520.

- Edelstein BL. Chronic disease management strategies of early childhood caries: Support from the medical and dental literature. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:281–287.

- Horst JA. UCSF protocol for caries arrest using silver diamine fluoride: Rationale, indications, and consent. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2016;44:16–28.

- Shah S, Bhaskas V, Venkataraghavan K, et al. Efficacy of silver diamine fluoride as an antibacterial as well as antiplaque agent compared to fluoride varnish and acidulated phosphate fluoride gel: An in vivo study. Indian J Dent. 2013;24:575–581.

- Yee R, Holmgren C, Mulder J, et al. Efficacy of silver diamine fluoride for arresting caries treatment. J Dent Res. 2009;88:644–647.

- Mouradian WE, Wehr E, Crall JJ. Disparities in children’s oral health and access to dental care. JAMA. 2000;284:2625–2631.

- Vargas CM, Ronzio CR. Disparities in early childhood caries. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6(Suppl 1):S3.

- Savage JS, Fisher JO, Birch LL. Parental influence on eating behavior: Conception to adolescence. J Law Med Ethics. 2007;35:22-–34.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. State Medicaid Payment for Caries Prevention Services by Nondental Professionals. Available at: www2.aap.org/oralhealth/ docs/OHReimbursementChart.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2017.

- Hale KJ, American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Pediatric Dentistry. Oral health risk assessment timing and establishment of the dental home. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1113–1116.

- Foster T, Perinpanayagam H, Pfaffenbach A, et al. Recurrence of early childhood caries after comprehensive treatment with general anesthesia and follow-up. J Dent Child (Chic). 2006;73:25–30.

- Oliveira AF, Chaves AM, Rosenblatt A. The influence of enamel defects on the development of ECC in a population with low socioeconomic status: A longitudinal study. Caries Res. 2006;40:296–302.

- Salone LR, Vann WF,Jr, Dee DL. Breastfeeding: an overview of oral and general health benefits. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:143–151.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2017;15(4):48-51.