OBENCEM/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

OBENCEM/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Providing Care to Patients With Special Needs

As more adults with special needs seek oral health care in the private practice setting, clinicians need to be prepared to offer safe and effective treatment.

This course was published in the August 2019 issue and expires August 2022. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the prevalence of disabilities in the United States population, and list examples of patients with special needs and disabilities who commonly present in dental practice.

- Explain key information that should be included in the patient history when caring for this population.

- List clinical strategies and techniques that can enhance outcomes when caring for individuals with special needs or complex medical histories.

Special care dentistry is the branch of oral health care that treats people with special needs, including those with physical, medical, developmental, or cognitive conditions that limit their ability to receive routine dental care.1 The 2010 United States census reports that about 56.7 million Americans—or one out of every five—live with a disability.2 The Americans with Disabilities Act defines a person with a disability as someone with physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.3 Additionally, as patients continue to live longer, their health histories become more complex. Unfortunately, people with special needs often report difficulties finding dentists who are willing to treat them, leading to increased rates of periodontal diseases, caries, and other oral problems.4,5 This article will explore treating adults with special needs and complex medical conditions. It will also review the process of evaluating special needs, accessing a patient’s level of cooperation, treatment planning, management techniques, and sedation.

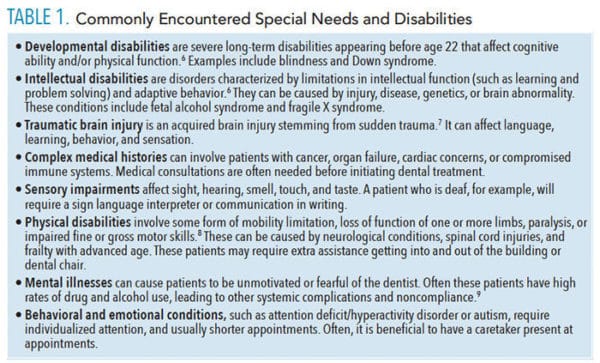

Effective care hinges on understanding the patient’s medical condition. Table 1 provides examples of commonly encountered special needs and disabilities.6–10 The Americans with Disabilities Act prohibits discrimination in access to services against people with disabilities. It requires dental offices to make reasonable accommodations for patients.10 Adequate parking and ramps must be available for patients with limited mobility. Placing handrails in the office can help patients with balance. Doorways, restrooms, and operatories should be large enough to accommodate wheelchairs and walkers.

Treating individuals with complex medical histories and disabilities requires skill, empathy, and a willingness to adjust to their changing needs. Some patients and caregivers will benefit from a tour of the clinic and introduction to the team before the first appointment. Several team members should be available for the appointment, as more than one assistant may be required.

APPOINTMENT SCHEDULING

When a patient with special needs contacts the clinic, the receptionist should ascertain as much information as possible. Typically, a patient or caregiver can describe the patient’s major medical concerns, any requested accommodations, and preferred appointment timing. The patient should be instructed to bring contact information for his or her physician(s) to the first appointment in case a medical consultation is necessary.

This is also the time to ask if the patient is able to consent for treatment. If the individual is unable to consent, the patient’s legal guardian or person with power of attorney (POA) must do so prior to initiating treatment. Legal paperwork should be brought to the first appointment and scanned into the patient’s chart. Because the legal guardian or individual with POA might not be the patient’s regular caregiver, providers are advised to consult state regulations for specific requirements for consent.

MEDICAL AND DENTAL HISTORY

Whether the first appointment is an emergency appointment or comprehensive examination, an accurate health history must be obtained before treatment. In conjunction with questioning the patient or caregiver, use of a health history form is recommended. The provider should determine the patient’s past and current medical conditions, along with any medications, allergies, surgeries and hospitalizations.

The extent of a patient’s disabilities, and how they impact the patient’s life and home hygiene, should be documented. Furthermore, oral health professionals should be aware of dental anomalies associated with the individual’s medical history. Examples include patients with Down syndrome and congenitally missing teeth, or gingival hyperplasia caused by dilantin. The history should include any problems with the liver or kidneys that may affect how medications are metabolized, which would impact prescription decisions (note: unfamiliar medications should be referenced via a drug database).

Some patients may require antibiotic prophylaxis,11 and because indications for its appropriate use change periodically, clinicians are advised to consult the American Dental Association’s guidelines.12

Treating patients with multiple health conditions often involves the need to collaborate with the patient’s medical team. A written medical consultation should confirm the patient’s existing medical diagnoses and medications, explain proposed use of local anesthetics or sedation, list needed treatments, and request any specific details required. Relevant information from a consultation may include international normalized ratios, hemoglobin A1c levels, the timing of dental treatment during chemotherapy or radiation treatment, and if epinephrine should be avoided due to cardiac history. After consulting with a physician, it might be determined that a patient will need antibiotic premedication due to a weakened immune system or other comorbidities.

The patient’s past dental history and chief concern must be investigated (Table 2), especially if there has been a lapse in dental care. The patient might be experiencing pain or have recently noticed loose teeth. Caregivers often bring in noncommunicative patients after they have stopped eating and are losing weight due to lack of nutrition. Another reason individuals with complex health needs pursue oral care is due to a physician’s request for dental clearance prior to cardiac or transplant surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiation treatment.

Speaking with the patient or caregiver about past dental experiences provides information useful in determining how to effectively treat the patient in the clinic, or if the patient is better treated in an alternative setting.13

![]() SEDATION

SEDATION

The decision to use any type of sedation must be based on the patient’s cooperation, health history, and the extent of treatment. Providers who administer sedation need to be trained and certified according to state laws. The patient’s vitals must be monitored during the procedure, and the provider must have the appropriate life skills certification and know how to manage medical emergencies that could result from sedation. The following synopsis reviews various types of dental sedation:

Inhalation sedation involves using nitrous oxide and oxygen to decrease anxiety in fearful or anxious patients. The individual is awake during the procedure, and must be cooperative enough to inhale gases and keep the nasal hood in place.14

Oral sedation requires oral medications prior to the procedure. Depending on the dosage and type of medication, sedation will be minimal to moderate. The patient is usually awake or sleepy.15

Intravenous (IV) sedation is a drug-induced depression of consciousness that provides moderate sedation.16 The recommendation is to have a dental anesthesiologist or physician administer IV sedation while the dentist works on the patient, who must cooperate and allow venipuncture.

General anesthesia is appropriate for patients who are uncooperative and have extensive dental needs. In these cases, it is often necessary to refer patients to hospital-based dental programs.

WHEELCHAIRS

Consideration must be given to patients with wheelchairs. Oral health professionals need to determine if patients are able to transfer to the dental chair by themselves or with the help of a caregiver and/or sliding block. The armrest on the dental chair should be removed, and the chair should be at the level of the wheelchair or slightly lower. The rheostat pedal, headlight, and any hoses should also be cleared for the transfer.17 If the dental team will assist in the transfer, members must be properly trained to ensure patient safety and prevent falls. Once the patient is seated, he or she will need to be positioned, centered, and reclined for treatment. Extra pillows, cushions, and support pads can be used to keep the patient comfortable. Treatment may need to stop periodically to allow the patient to reposition if he or she starts to lose muscle control.

Not all patients in a wheelchair will be able to transfer to the dental chair. Some shouldn’t transfer due to the risk of dislodging urinary catheters or breathing tubes that are connected to a power source on the wheelchair. Others will not want to transfer because they feel vulnerable or unsafe. If the clinic has a dental chair that can be moved out of the way, the wheelchair can be placed in the operatory. An office that plans on providing special care dentistry should invest in dental chairs that easily move to accommodate wheelchairs. A reusable headrest can be purchased that snaps onto the back of wheelchairs that don’t recline.

Radiographs can be taken on patients in wheelchairs with the use of a portable X-ray unit. Another piece of equipment to consider is a wheelchair lift, which is a dental platform that can recline patients in their own wheelchairs. If a patient has extensive dental needs and cannot recline utilizing available equipment, consider a referral to a clinic or hospital-based dental program where lift teams and specialized equipment can assist in transfers.

PATIENT MANAGEMENT

Behavioral management techniques used in pediatric dentistry can often be applied to people with special needs, particularly on patients with intellectual disabilities. Throughout the procedure, the team should provide positive reinforcement.18 Depending on the patient’s cognitive level, the oral health professional might have to repeat instructions several times. Direct observation can help patients who have not received significant dental care in the past; this involves allowing patients to watch a video or a patient directly being treated.18 Having the patient’s caregiver pose as a patient in the dental chair, and permitting the patient to touch the chair, air-water syringes, and lights can make a hesitant patient more relaxed. Patients who can communicate should be encouraged to ask questions.

Tell-show-do and distraction techniques are also helpful.18 Tell-show-do requires clinicians to explain the procedure using terminology the patient understands. The provider should demonstrate the procedure and perform the activity exactly as described and demonstrated. This familiarizes the patient with treatment and lets the oral health professional set expectations for the appointment. Alternatively, distraction can be used to divert attention from the procedure to something more soothing and enjoyable.18 Consider having the patient watch movies or hold onto a blanket.

PROTECTIVE STABILIZATION

Protective stabilization is the restriction of patient’s freedom of movement with or without the patient’s permission—to decrease risk of injury to the patient and provider.18 The use of protective immobilization is controversial because it can cause psychological harm and violate the patient’s rights if performed unethically or without consent. Stabilization should never be used out of convenience; it should only be considered out of necessity, and the minimum stabilization required should be used. Examples of person-based immobilization are having someone hold the patient’s hands down and maintaining the head in position during the procedure. Papoose boards and body stabilization wraps can also be used, but a strong, determined patient could break away from the restraints.

The oral health professional must communicate with the caregiver to evaluate the appropriateness of protective immobilization. The patient’s emotional and cognitive levels and any past use of restraints should be evaluated. Another consideration is urgency of treatment (eg, a dental emergency). Informed consent should always be obtained. Treatment notes should reflect why stabilization was needed, the type used and for how long, and how the patient tolerated the procedure.18

TREATMENT PLANNING

The fundamental process of treatment planning is similar in patients with or without complex needs. A thorough clinical and radiographic examination should be completed. Throughout the exam and treatment, the oral health professional must be aware of any dental-related sequelae associated with any medical conditions, the patient’s ability to cooperate, and the patient’s self-care regimen. The five major stages of treatment are briefly outlined as follows:

Emergency: Emergent dental problems, such as swelling, abscesses, and painful teeth, should be the first priority in care. Hopeless teeth should be extracted. Eliminating dental infections is a priority so they don’t spread to the head, neck, or body. When appropriate, prescriptions for antibiotics or pain medication should be offered.

Periodontal stability: The periodontium must be assessed, appropriate periodontal treatment performed, and oral hygiene instructions issued.

Caries control: Teeth with caries lesions should be restored, with consideration given to the ability of the patient to keep his or her mouth open, isolation of the teeth, and the restorative material used. If a patient can tolerate a rubber dam, it offers the benefits of isolation and protection of the oral cavity.

Replace missing teeth: Patients should be offered all appropriate options for replacing teeth, such as bridges, implants, and removable dentures. Before initiating removable prosthetic treatment, ensure the patient can tolerate impressions, has the manual dexterity to insert and remove the prosthetic, and that a removable appliance does not pose a choking hazard.

Establish a Maintenance Schedule: In an effort to prevent additional dental problems, a recare interval should be established for routine prophylaxes and periodic exams.

Self-CARE

The ability of the patient or caregiver to participate in self-care cannot be underestimated. Poor oral hygiene can rapidly lead to the failure of well-intentioned dental treatment, as well as compromise oral and systemic health. Clinicians should identify the reasons for poor oral care. It could be a combination of a diet high in sugar or acidic substances, inability to brush or floss, or not knowing the importance of oral hygiene. The dental team should make sure patients understand the necessity of home hygiene, and provide detailed self-care instruction at a cognitive level the patient or caregiver understands.

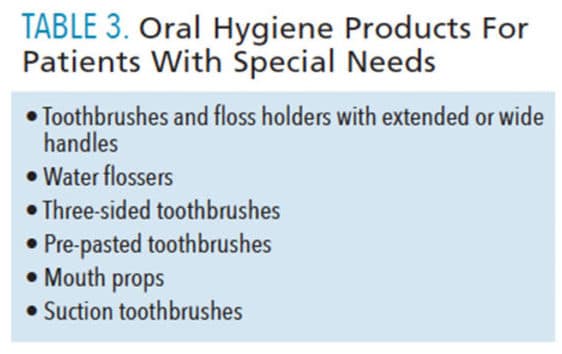

Patients and caregivers benefit from having clinicians demonstrate oral hygiene techniques, and repeating the techniques to ensure understanding. For patients with limited dexterity, teams should recommend relevant home modifications and dental products designed for people with special needs (Table 3). Patients living in medical care facilities with caregivers typically bring paperwork that provides recommendations for the patient. A detailed note explaining the frequency, duration, how to brush and floss, and the request for help from a caregiver in the facility can improve oral care.

CONCLUSION

When treating patients with special needs and complex medical histories, each patient must be treated as an individual who is not defined by a medical condition or disability. Oral health professionals can fill the void in dental care for these individuals by making sure the office can accommodate patients with complex needs, understanding the patient’s medical and dental histories, and making modifications to dental treatment. Caring for these patients often requires collaborating with other health care professionals and using specialized resources (such as the Special Care Dental Association and American Dental Association) to ensure optimal oral health outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Special Care Dentistry Association. SCDA Definitions. Available at: scdaonline.org/page/SCDADefinitions. Accessed March 25, 2019.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Nearly 1 in 5 People Have a Disability in the U.S. Available at: census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/miscellaneous/cb12-134.html. Accessed June 6, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. A Guide to Disability Rights Laws. Available at: ada.gov/cguide.htm. Accessed June 6, 2019.

- Brown LF, Ford PJ, Symons AL. Periodontal disease and the special needs patient. Periodontol 2000. 2017;74:182–193.

- Albino JE, Inglehart MR, Tedesco LA. Dental education and changing oral health care needs: disparities and demands. J Dent Educ. 2012;76:75–88.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Available at: report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/ViewFactSheet.aspx?csid=100. Accessed June 6, 2019.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Traumatic Brain Injury Information Page. Available at: ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Traumatic-Brain-Injury-Information-Page. Accessed June 6, 2019.

- Piatt JA. Physical disability. In: The SAGE Encyclopedia of Lifespan Human Development. Bornstein MH, ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications Inc; 2018:1647–1649.

- Matevosyan NR. Oral health of adults with serious mental illnesses: a review. Community Ment Health J. 2009;46:553–562.

- U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities. Available at: ada.gov/medcare_mobility_ta/medcare_ta.htm. Accessed June 6, 2019.

- Glenny AM, Oliver R, Roberts GJ, Hooper L, Worthington HV. Antibiotics for the prophylaxis of bacterial endocarditis in dentistry. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD003818.

- American Dental Association. Antibiotic Prophylaxis Prior to Dental Procedures. Available at: ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/antibiotic-prophylaxis. Accessed June 6, 2019.

- Glassman P, Subar P. Planning dental treatment for people with special needs. Dent Clin North Am. 2009;53:195–205.

- Malamed S. Sedation: A Guide To Patient Management. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2019:182.

- Sebastiani FR, Dym H, Wolf J. Oral sedation in the dental office. Dent Clin North Am. 2016;60:295–307.

- Southerland JH, Brown LR. Conscious intravenous sedation in dentistry: a review of current therapy. Dent Clin North Am. 2016;60:309–346.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Wheelchair Transfer: A Health Care Provider’s Guide. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-09/wheelchair-transfer-provider-guide.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2019.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Behavior Guidance for the Pediatric Dental Patient. Available at: aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_Behav Guide.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2019.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July/August 2019;17(7):46–49.

SEDATION

SEDATION