The Re-Emergence of Measles

What oral health professionals need to know about the signs, symptoms, and public health implications of this preventable but highly contagious disease.

This course was published in the May/June 2025 issue and expires June 2028. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 148

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define measles.

- Discuss the causes of the re-emergence of measles.

- Identify the extraoral and intraoral signs and symptoms of measles.

- Outline the appropriate steps to take if a measles exposure occurs in the dental office.

Once considered eliminated in many parts of the world, measles is experiencing a concerning resurgence. Driven by misinformation, vaccine hesitancy, and gaps in immunization coverage, outbreaks are now threatening public health. Oral health professionals should be knowledgeable of the causes behind the re-emergence of measles, its impact, and strategies to combat its spread.

History of Measles

First identified as an infectious disease in 1757 by a Scottish physician, Francis Home, the United States started recording all cases of measles in 1912. Prior to vaccination, most children contracted measles by age 15 with an estimated 4 million people in the US infected each year. These infections led to 400 to 500 deaths, 48,000 hospitalizations, and 1,000 cases of encephalitis annually.1

In 1954, John F. Enders, PhD, an American virologist and microbiologist, and Thomas C. Peebles, MD, and American physician, isolated the measles virus from the blood of a 13-year-old patient while collecting blood samples during a measles outbreak in Boston. In 1963, Enders and colleagues developed a vaccine from the Edmonston-B strain.1

In 1968, the Edmonston-Enders vaccine, an improved and weaker version of the initial vaccine, was developed by microbiologist Maurice Hilleman, PhD, and colleagues.1 The gold standard since then, it is currently combined with mumps and rubella for the MMR vaccine or additionally with varicella (chicken pox) to create the MMRV vaccine.2

Due to risk of hospitalization and death associated with measles, the goal of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was to eradicate measles by 1982. Although there was an 80% reduction in cases due to the use of the measles vaccine, the goal of eradication was not met.1

Subsequently, a 1989 measles outbreak in vaccinated school-aged children initiated the addition of a second MMR dose in the childhood vaccination series.1 The first dose is typically given at age 12 to 15 months and it provides 93% efficacy against measles. The second dose at age 4 to 6 increases efficacy to 97%.2

Elimination of Measles

In 2000, the CDC declared the measles virtually eliminated in the US due to a very effective vaccination program.1 The US population was protected by herd immunity, or population immunity. This occurs when 95% or more of the population is immune to a disease either through vaccination or previous infection.3

Unfortunately, this does not mean that there were no cases of measles. An elimination status for a disease indicates that no new cases are being contracted from within the country for more than 12 months and that new cases are only identified to be from travel outside the US.1,3 Therefore, it is important to maintain a high percentage of vaccinated individuals to minimize opportunity transmission.

Re-Emergence of Measles

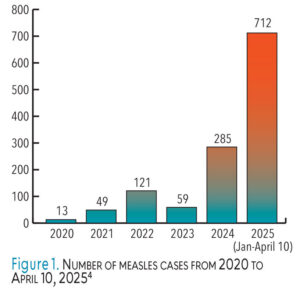

Measles cases have been on the rise with continued incremental increases annually and a surge in 2022.4 Figure 1 shows the number of cases per year since 2020.4

In 2024, 285 measles cases were reported for the entire year. Alarmingly, in just the first 3.5 months of 2025, 712 cases have been reported by 25 states with three deaths. Of these cases, 225 were in children younger than age 5, 274 were age 5 to 19, 198 were age 20 or older, and in 15 cases, age was not reported. Of these cases, 97% were unvaccinated or unknown vaccination status, 1% had one MMR dose, and 2% had the two-dose series. Additionally, 11% of these cases (79 out of 712) have led to hospitalizations.4

So what is causing this re-emergence of measles? Plainly speaking, vaccination rates have dropped. Many Americans are choosing not to get vaccinated or have their children vaccinated. Rampant misinformation and disinformation about vaccines, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, have public health officials worried about outbreaks becoming more common.5

So what is causing this re-emergence of measles? Plainly speaking, vaccination rates have dropped. Many Americans are choosing not to get vaccinated or have their children vaccinated. Rampant misinformation and disinformation about vaccines, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, have public health officials worried about outbreaks becoming more common.5

Between the 2019–20 and 2023–24 school years, the national average of kindergarteners vaccinated against MMR dropped from 95.2% to 92.7%. Additionally, the 2023-2024 school year records report an increase in vaccine exemption forms to 3.3% nationally in 41 jurisdictions, 14 of which exceed 5%.6 Exemption forms allow parents to decline any of the childhood vaccinations for their children for religious, medical, or personal reasons.7

Medical exemptions are accepted by all states while religious and personal exemptions are accepted on a more limited basis. In 30 states, religious exemptions are allowed, 13 allow exemptions for religious and personal reasons, two do not specify the nature of the nonmedical exemption, and five states do not allow any type of nonmedical exemption.7 Additionally, students are allowed to attend school on temporary waivers while they are working on completing the required immunizations.7 From a public health perspective, this is alarming. Currently, 40 states fall below the 95% vaccination rate needed to maintain herd immunity.4

The growth of measles in the US is also due to increased global measles activity. Travel in and out of the US by unvaccinated individuals increases the risk of bringing an active case of measles into the country.3 The public needs to be better educated about the safety and benefits of childhood vaccinations and ensure students begin school fully vaccinated. In addition, those who are traveling should also be made aware of the increased risk of contraction outside of the US.

Signs, Symptoms, and Transmission

Measles is a viral infection caused by the rubeola virus. It is highly contagious and spreads in multiple ways including respiratory droplets that pass through the air via talking, coughing, and sneezing; fomites, such as door handles and elevator buttons; and person-to-person by sharing /food/drinks, kissing, and shaking hands. Due to its aerosol transmission, the winter and spring months bring a rise in cases due to people staying indoors more due to weather. The incubation period is 7 to 14 days before symptoms begin; however a person is contagious 4 days before and 4 days after symptoms appear.3,8

Measles is a viral infection caused by the rubeola virus. It is highly contagious and spreads in multiple ways including respiratory droplets that pass through the air via talking, coughing, and sneezing; fomites, such as door handles and elevator buttons; and person-to-person by sharing /food/drinks, kissing, and shaking hands. Due to its aerosol transmission, the winter and spring months bring a rise in cases due to people staying indoors more due to weather. The incubation period is 7 to 14 days before symptoms begin; however a person is contagious 4 days before and 4 days after symptoms appear.3,8

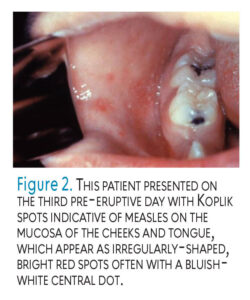

Symptoms begin with an unusually high fever (104°+) along with the three Cs: cough, conjunctivitis, and coryza (runny nose). Following initial symptoms, Koplik spots may appear on the buccal mucosa (Figure 2). Three to 5 days after symptoms begin, a flat, red rash, commonly starting at the hairline, travels down the body to the neck, trunk, legs, and feet (Figure 3). The rash may have singular raised bumps or they may coalesce and join.3,8

Within 5 to 7 days, the rash begins to disappear in the order at which it appeared with the most ill days being at the peak of the rash.3,8 In some cases, individuals have reported ear infections and diarrhea as well. Risk factors include young children (younger than age 5), adults older than age 20, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals.2 Severe complications have also been reported including hospitalization (one in five unvaccinated people); pneumonia (one in 20 children); encephalitis, which can lead to convulsions, loss of hearing, and intellectual disabilities (one in 1,000 children); death from respiratory and neurological complication (one to three out of every 1,000 children); and premature birth or low birth weight babies in pregnant women.3,8

Within 5 to 7 days, the rash begins to disappear in the order at which it appeared with the most ill days being at the peak of the rash.3,8 In some cases, individuals have reported ear infections and diarrhea as well. Risk factors include young children (younger than age 5), adults older than age 20, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals.2 Severe complications have also been reported including hospitalization (one in five unvaccinated people); pneumonia (one in 20 children); encephalitis, which can lead to convulsions, loss of hearing, and intellectual disabilities (one in 1,000 children); death from respiratory and neurological complication (one to three out of every 1,000 children); and premature birth or low birth weight babies in pregnant women.3,8

Diagnosis and Treatment

Due to its classical presentation of fever, rash, and the three Cs, measles is often diagnosed clinically by a healthcare provider. Laboratory confirmation can be made but is often not needed. Differential diagnosis may include varicella, toxic shock syndrome, infectious mononucleosis, Epstein-Barr, an allergic drug reaction, scarlet fever, German measles (rubella), Rocky mountain spotted fever, and fifth disease after rash development. This is important as it leads to effective treatments for illnesses.9,10

Because measles is caused by a virus, treatment includes staying well hydrated with fluids, fever-reducing medications, and rest. Intravenous rehydration may be needed. Isolation of 4 days before (although many are unaware of their illness) to 4 days after the rash appears is important to decrease the spread of the illness to nonvaccinated individuals.9,10

Measles and Oral Health Professionals

Due to the increase in cases, oral health professionals should be able to identify the extraoral signs and symptoms of measles, as well as intraoral manifestations. Koplik spots are a characteristic sign of measles that occur intraorally and usually appear a day before the skin rash (Figure 1). Most often located opposite the first molars on the buccal mucosa, but also possible on the labial mucosa and soft palate, they have commonly been referred to as “grains of salt on a red background” with a tell-tale appearance of bluish-white spots on a red background, slightly raised with a diameter of 2 to 3 mm.11

Occurring in approximately 60% to 70% of individuals with measles, oral health professionals are likely to see Koplik spots before the rash appears and may assist in a prediagnosis of the patient.11 One of the first lines of defense against the spread of infectious diseases in a dental practice is to call patients the day prior to their appointment. At this time, the front desk can ask basic questions regarding patients’ health (eg, are they feeling well, have they had a fever in the past 24 hours, and if they have noticed any other signs/symptoms of illness). If so, the appointment should be canceled until the patient is asymptomatic.12

If patients do not report anything of concern, they should arrive at the appointment early, in which the second line of defense is to take a full assessment of the patient’s medical history, including vaccinations. This is especially important for new patients or those in the childhood vaccination age group. At this time, the opportunity to encourage missed vaccinations may arise.12

As one of the first symptoms of measles is hyperpyrexia (high fever), taking the patient’s temperature is also recommended. If a patient enters the office with any signs and symptoms of measles, appropriate infection control precautions should be taken.12

The entire dental team should also be up to date on vaccinations to decrease the spreading of infectious diseases.12,13 The CDC recommends that all adults ensure they are protected against measles, mumps, and rubella with one or two doses of the MMR vaccine, depending on their individual risk factors unless they have other evidence of immunity. For most adults, one dose of the MMR vaccine or other proof of immunity is adequate. In areas without an active outbreak, routine screening for measles immunity among adults is not typically necessary. Additionally, testing for antibodies after vaccination is not required. There is no catch-up recommendation for a second dose in adults, including those born before 1989.14 The dental office should keep precise records on all staff members’ vaccination records.15

The deferral of dental treatment for patients with measles symptoms is required; they should be sent home with advice to call their primary care physician. This will eliminate the possibility of additional exposures. Documentation of the suspected measles case must also be reported to the state health department for monitoring of a potential outbreak and to inform other potentially exposed individuals.12

The Dental Office Post-Exposure

The best defense against the spread of any infectious disease in the dental setting is to follow standard universal precautions at all times.15 The measles virus can live on surfaces and in the air for up to 2 hours after an infected person has left the area. If the patient exhibited coughing and sneezing without a mask while in the office, or a dental procedure involving aerosol production took place, individuals should stay out of the area for several hours until the air and environmental surfaces no longer pose an exposure hazard. The operatory should not be used until the aerosols have had adequate time to land.13

Waiting and treatment rooms should be disinfected if a patient is suspected of measles. Additionally, office staff should wear respiratory protection (N95 or better) in areas where an infected person has been within the past 2 hours. Other personal protective equipment, including gloves, gowns, and eyewear, should be worn, and surfaces that are commonly contaminated (countertops, tables, chairs, doorknobs, etc) need to be thoroughly wiped down with a US Environmental Protection Agency-registered disinfectant. The effectiveness of the disinfectant depends on proper use so it is imperative that the label directions be followed carefully, including contact time.13 Good hand hygiene practices are always important as well.

Conclusion

Measles was once thought to be eliminated in the US based on the recommended and achieved 95% herd immunity rate. It is a highly contagious, preventable disease that is making a notable comeback. Measles can lead to serious complications, such as pneumonia, encephalitis, and even death, particularly in young children and immunocompromised individuals.

Herd immunity is essential in keeping measles under control, safeguarding those who cannot be vaccinated, and maintaining public health. A continued drop in vaccination rates can quickly lead to a public health crisis. Continued vaccination efforts are needed to address the resurgence of measles. As oral health professionals are at high risk of exposure due to close patient contact and aerosol-generating procedures, following standard universal precautions is critical.

Oral health professionals should ensure they are vaccinated against measles to reduce their own risk and prevent the spread to patients. In addition, they play a key role in advocating for vaccinations to reduce the prevalence of all infectious diseases in the US.

References

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. History of Measles. Available at cdc.g/v/measles/about/history.html. Accessed April 17, 2025.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles Vaccination. Available at cdc.gov/measles/vaccines/index.html. Accessed April 17, 2025.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Measles. Available at cdc.gov/measles/about/index.html. Accessed April 17, 2025.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles Cases and Outbreaks. Available at cdc.gov/measles/data-research/index.html. Accessed April 17, 2025.

- Rozen A. Measles outbreaks in the US highlight the importance of vaccination. Available at publichealth.jhu.edu/떙/what-to-know-about-measles-and-vaccines. Accessed April 17, 2025.

- Seither R, Yusuf OB, Dramann D, et al. Coverage with selected vaccines and exemption rates among children in kindergarten – United States, 2023-24 school year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73:925-932.

- National Conference of State Legislatures. State Non-Medical Exemptions from School Immunization Requirements. Available at ncsl.org/health/state-non-medical-exemptions-from-school-immunization-requirements. Accessed April 17, 2025.

- Cleveland Clinic. Measles (Rubeola). Available at /my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/켸-measles. Accessed April 17, 2025.

- Chen S, Steele RW. Measles differential diagnosis. Available at https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/霌-differential?form=fpf. Accessed April 17, 2025.

- Koenig KL, Alassaf W, Burns MJ. Identify-isolate-inform: a tool for initial detection and management of measles patients in the emergency department.J est J Emerg Med. 2015;16:212-219.

- Jain P, Rathee M. Koplik Spots. Treasure Island, Florida: StatPearls; January 2024.

- Gordon S, MacDonald N. The safest dental visit: managing measles in the dental practice: a forgotten foe makes a comeback. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146:558-560.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Measles: Control and Prevention. Available at osha.gov/measles/control-prevention. Accessed April 17, 2025.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles Vaccine Recommendations, Information for Healthcare Professionals. Available at cd/.gov/measles/hcp/vaccine-considerations/index.html. Accessed April 17, 2025.

- American Dental Association. Infectious Diseases: Measles. Available at /ada.org/resources/practice/practice-management/patients/infectious-diseases-measles. Accessed April 17, 2025.

Figure 1: United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Domain; Figure 2: EyeEm Mobile GmbHMaisheva / istock / getty images plus

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May/June 2025; 23(3):28-31.