Kosamtu / E+

Kosamtu / E+

A Look at Peri-Implant Disease Classification

SUBSCRIBE TO THE PERIO UPDATE NEWSLETTER HERE

Implant therapy is often the treatment of choice when it comes to addressing tooth loss. And for the most part, it is quite successful. However, as dental hygienists are well aware, some implants fail. As such, clinicians are charged with detecting and addressing the signs of peri-implant disease. A conference of the American Academy of Periodontology and European Federation of Periodontology created diagnostic categories to properly prepare clinicians to best support their patients’ implant health.

This Perio Update will discuss the peri-implant health and peri-implant mucositis categories while the September 7 edition will cover peri-implantitis in addition to bony reattachment.

Because the presence or a history of periodontitis has been strongly linked to peri-implant conditions, patients diagnosed with peri-implant health should be seen based on their periodontal diagnosis. This means individuals diagnosed with implant and periodontal health should be seen at least annually. Those with healthy peri-implant tissues and gingivitis could be seen twice annually, while patients with a diagnosis of periodontitis should be seen more frequently. Active periodontitis should be addressed, and appropriate therapy applied, with the goal of stabilizing the periodontium until the periodontal condition is controlled. Studies have found patients who follow suggested recare intervals and maintain periodontal health are less likely to develop peri-implant disease than noncompliant individuals.1,2

Peri-implant mucositis occurs frequently3 and is assumed to precede bone loss.4 Therefore, prompt treatment is warranted. Improved oral hygiene, in conjunction with professional therapy, has been strongly related to the clinical reversal of this condition.5 Biofilm removal from the implant surface by the patient can be complicated by surface roughness, as well as the design of the implant and implant prosthesis. Recontouring the prosthesis to allow improved access for oral hygiene is often helpful. Thus, clinicians should reinforce effective self-care in order to reduce the microbial load on and around the implant.

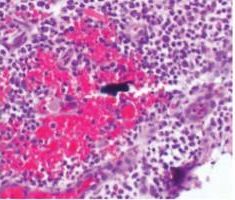

Currently, there are two broad schools of thought as to how this is best achieved. One group aims to reduce biofilm with minimal abrasion of the implant surface. The rationale is that titanium particles have been associated with inflammatory peri-implant disease, and these particles can be generated even with minimal pressure on the implant surface (Figure 1).6–8 At present, concern for generation of these particles is not widely supported; however, the possible significance should not be discounted. If these particles do play a role in peri-implant disease, attempts should be made to reduce their production. One technique is a low-abrasion method to reduce the biofilm load using sterile saline on a cotton pellet to gently clean the implant surface. This has been shown to ameliorate or eliminate peri-implant mucositis.9,10 At the same visit, the soft tissue surrounding the implant is gently cleaned with a metallic curet, with its blade turned toward the sulcus wall, away from the implant surface. In some cases, a prescription for a chlorhexidine mouthrinse to be used twice daily is appropriate.

If, in the clinician’s opinion, the generation of titanium particles is not related to the disease process, alternative methods for cleaning the implant surface can be used. Instruments suggested by the second school of thought include manual, sonic, and ultrasonic scalers, as well as air powder abrasives. Recent data have shown these particles are produced by multiple instruments, including stainless steel, titanium, and polyetheretherketone plastic tips.11

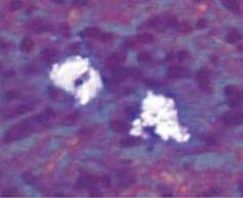

Regardless of the approach taken, a reevaluation at 1 month is appropriate. Any remaining evidence of peri-implant mucositis may require more aggressive therapy. In cases with cemented restorations, this continued problem has often been found to be related to excess cement particles on the implant surface or in the peri-implant soft tissues (Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4).12 If the clinician suspects this is the genesis and the inflammation process is not controlled by other methods, surgical intervention may be appropriate. This surgical therapy is designed to remove any excess cement on the implant surface, as well as cement and titanium particles in the surrounding soft tissues. If surgical therapy is warranted, the use of the dental videoscope is suggested.13 In these refractory cases, referral to a specialist should be strongly considered.

References

- Rodrigo D, Martin C, Sanz M. Biological complications and peri-implant clinical and radiographic changes at immediately placed dental implants. A prospective 5-year cohort study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23:1224–1231.

- Costa FO, Takenaka-Martinez S, Cota LO, Ferreira SD, Silva GL, Costa JE. Peri-implant disease in subjects with and without preventive maintenance: a 5-year follow-up. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:173–181.

- Pontoriero R, Tonelli MP, Carnevale G, Mombelli A, Nyman SR, Lang NP. Experimentally induced peri-implant mucositis. A clinical study in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1994;5:254–259.

- Caton JG, Armitage G, Berglundh T, et al. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions — introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J Periodontol. 2018;45(Suppl 1):S1–S8.

- Salvi GE, Aglietta M, Eick S, Sculean A, Lang NP, Ramseier CA. Reversibility of experimental peri-implant mucositis compared with experimental gingivitis in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23:182–190.

- Wilson TG Jr, Valderrama P, Burbano M, et al. Foreign bodies associated with peri-implantitis human biopsies. J Periodontol. 2015;86:9–15.

- Eger M, Hiram-Bab S, Liron T, et al. Mechanism and prevention of titanium particle-induced inflammation and osteolysis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2963.

- Mombelli A, Hashim D, Cionca N. What is the impact of titanium particles and biocorrosion on implant survival and complications? A critical review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2018;29(Suppl 18):37–53.

- Kolonidis SG, Renvert S, Hammerle CH, Lang NP, Harris D, Claffey N. Osseointegration on implant surfaces previously contaminated with plaque. An experimental study in the dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14:373–380.

- Ramesh D, Sridhar, S, Siddiqui D, Valderrama P, Rodrigues D. Detoxification of titanium implant surfaces: evaluation of surface morphology and bone-forming cell compatibility. J Bio-and Tribo Corrosion. 2017;3:1–13.

- Harrel SK, Wilson TG Jr, Pandya M, Diekwisch TG. Titanium particles generated during ultrasonic scaling of implants. J Periodontol. 2019;90:241 246.

- Linkevicius T, Puisys A, Vindasiute E, Linkeviciene L, Apse P. Does residual cement around implant-supported restorations cause peri-implant disease? A retrospective case analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2013;24:1179 1184.

- Wilson TG Jr. A new minimally invasive approach for treating peri-implantitis. Clin Adv Periodontics. 2019;9:59–63.

This information originally appeared in Wilson T. Supporting implant health and managing peri-implant diseases. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2020;18(6):40-43.