Connecting the Mouth and Mind in Patients With Alzheimer Disease

Recognizing how this common form of dementia shapes systemic and oral health is essential for delivering safe, individualized, and effective care.

This course was published in the January/February 2026 issue and expires February 2029. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 750

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the three stages of Alzheimer disease (AD).

- Explain the relationship between periodontal diseases and AD, including the role of oral bacteria.

- Assess the oral health challenges faced by patients with AD and the impact of cognitive decline on oral care and nutrition.

Neurological and/or cognitive issues, such as depression, delirium, dementia, and Alzheimer disease (AD), are common among older adults. While they may appear to have similar presentations, they can typically be diagnosed more definitively. Accurate diagnosis is essential to developing an effective treatment plan.1 Oral health professionals need to be knowledgeable about AD and its impact on systemic and oral health in order to provide high-quality patient care.

AD is anticipated to impact more than 12 million people worldwide by 2050.2 The disease, known for its initial effect on neuro/cognitive functioning, is caused by the presence of neurofibrillary tangles in the brain that cause brain synapses and neuron death.2 While post-mortem examination remains the definitive diagnostic method, AD can now be diagnosed with validated clinical criteria and biomarker evidence.

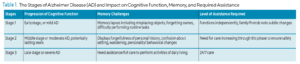

The progression of AD comes in three stages (Table 1).3 In the early or mild stage, the individual is able to function independently but begins to notice memory challenges. These memory lapses are often noticed, not only by the individual, but family and friends as well. In the second stage, moderate dementia, memory becomes worse. Assistance completing tasks associated with personal hygiene and food preparation may be needed in this stage. The final, or severe, stage requires around-the-clock care and includes the inability to complete activities of daily living.4

![]() Impact of Systemic Conditions

Impact of Systemic Conditions

Depression,5,6 gastrointestinal disease,7,8 cardiovascular disease,9-11 and type 2 diabetes12,13 often go hand in hand with AD. Comorbidities that occur simultaneously with AD increase the level of physiological dysfunction.14 The correlation between AD and other chronic conditions stems from the central mechanism of inflammation.15

The presence of systemic conditions may complicate the treatment of AD, especially as the disease progresses and dementia becomes apparent. The successful treatment of comorbidities may improve patient outcomes. Oral health professionals should be aware of any systemic conditions impacting their patients with AD in order to provide the most effective care and help patients and their families support long-term oral health.

In patients with AD, depression is more commonly experienced early in the diagnosis and is linked to the location of plaques in the brain. Antidepressants may be prescribed to support quality of life.6

Patients with AD may experience bowel habit changes, including constipation or diarrhea. Either can be triggered by changes in diet, medications, and behavioral changes.7,8 Providing fluids and nutrient-dense food, as well as encouraging mobility can minimize gastrointestinal irritation.

Cardiovascular disease in patients with AD is linked to hypertension and inflammation, especially in mid-life prior to the AD diagnosis. Noting these conditions early provides a window of opportunity to address diet, smoking, stress modification, and inflammation to improve patient quality of life.9,10

Current evidence indicates a link between AD and type 2 diabetes; specifically linking early onset of diabetes with dementia.11,12 Research is now examining the connection with a controlled, stable glucose level and AD.

Periodontal Pathogens

Periodontal diseases are among the most prevalent chronic inflammatory conditions, affecting two in five adults (42.2%) in the United States. Among those age 65 and older, the prevalence increases to nearly 60%.16 While periodontal diseases are localized oral conditions, evidence suggests their systemic implications extend far beyond the periodontium.

A possible correlation exists between periodontal diseases and the onset and progression of AD, with inflammation and periodontal pathogens playing recognized roles.17 Both conditions share common inflammatory pathways, particularly the involvement of cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α.18 These mediators contribute to tissue destruction including alveolar bone loss in periodontal diseases and neuronal degeneration in AD, suggesting a potential bidirectional relationship between oral and neurodegenerative health.19

More than 700 bacterial species are contained within the human oral microbiota, with each exhibiting different grades of pathogenicity toward the host.17,20 The microbiota form plaque and preferentially colonize on different surfaces in the oral cavity, forming a complex biofilm.17 In a healthy state, Gram-positive bacteria dominate the composition of plaque. As the biofilm matures, a progressive shift occurs from Gram-positive to predominately Gram-negative, anaerobic bacteria.20,21

These pathogenic bacteria, including Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, Tanerella forsythia, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Prevotella intermedia, and Fusobacterium nucleatum, release pro-inflammatory mediators that can travel to the bloodstream and cause cerebral inflammation, contributing to systemic inflammation.18,20,22 Interestingly, not all individuals with these bacteria will develop periodontal diseases, the virulence of each species alone is low and cooperation between the bacteria and an overzealous host-immune response is necessary for disease progression.20

The severity of periodontal diseases is influenced by host immune competence, genetic susceptibility ,and external factors including lack of proper oral hygiene, malnutrition, and chronic illness.23 This dysbiosis increases the risk for chronic inflammation, which may accelerate systemic pathologies such as AD.

Miklossy and McGeer24 showed a seven times higher density of oral bacteria in the brain tissue of post-mortem patients with AD compared to those without AD. Studies have detected elevated levels of P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum, and P. intermedia in patients with AD.17,25 However, results have been mixed and there is not currently a consistent association between specific bacterial species and AD pathology.26,27

Given the potential for periodontal inflammation to influence systemic disease through the diffusion of inflammatory mediators, routine periodontal maintenance should be viewed not only as a preventive strategy for oral health but as critical in reducing the risk and progression of AD. Early and consistent periodontal intervention may help lower systemic inflammatory burden, providing a valuable adjunct to the neurodegenerative disease.

Oral Health Concerns

Patients with AD are more likely to have substandard oral hygiene and poor oral health compared to individuals without cognitive impairment.28 This is largely due to the progressive neurogenerative nature of AD, affecting memory, motor skills, judgement, and problem solving. With the progression of the disease, patients may forget to perform daily oral hygiene tasks, lose the ability to perform these tasks, or may not recognize the importance of daily self-care.

Ming et al29 suggests that patients with AD have a reduced ability to identify pain or discomfort associated with periodontal diseases, gingival bleeding, or decay, and may not report oral health concerns. As a result, undiagnosed oral maladies may be present.

A high plaque index may be noted as individuals with AD often have irregular brushing habits.29 A meta-analysis looked at 22 observational studies to determine the association between oral health and AD.27 Individuals with AD had more significant periodontal disease markers, including high plaque index, increased gingival bleeding, higher probing depths, and greater loss of attachment compared to those without AD. Additionally, the number of proinflammatory biochemical mediators related to periodontal diseases was noticeably higher.27,28

Xerostomia, a common side effect of malnutrition and polypharmacy, can further impair oral health. Medications prescribed to manage AD include antihypertensives, antidepressants, and antipsychotics, which all contribute to a reduced salivary flow. Xerostomia can lead to increased biofilm accumulation, caries, periodontal diseases, fungal infections, candidiasis, and masticatory discomfort.30

Saliva substitutes or encouraging frequent sips of water may help alleviate symptoms and improve oral function. Xerostomia can also be related to burning mouth syndrome, reduced food intake, impaired salivary cleansing, and dysphagia, all impacting patient quality of life.16

Partial or full edentulism is a common occurrence among older adults with dementia, and may be due to a bidirectional relationship between diseases.22 Studies have shown that individuals with significant tooth loss may have an increased risk of cognitive decline, though the relationship is likely multifactorial and may reflect shared risk factors.29 Brain degeneration caused by AD can reduce sensation of smell and taste, appetite, and motor function, which impairs mastication.31 This can lead to reduced nutritional intake, increase malnutrition, worsening dementia symptoms, and diminished quality of life.32

Partnering With the Caregiver

As AD progresses, individuals lose the ability to maintain oral hygiene independently and must rely on a caregiver.33 Oral health professionals must recognize caregivers as key partners in managing care. The Alzheimer’s Association provides a vast array of resources to help the patient, caregiver, and healthcare professional access information pertinent to optimizing the standard of care for patients with AD.34

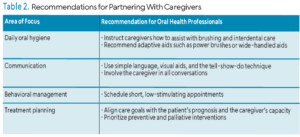

Partnering with the caregiver involves actively including them in all stages of oral healthcare such as shared decision-making, education, and demonstrating daily oral hygiene practices.

For individuals with AD, the caregiver and oral health professional should consider the longevity of treatment, maintenance, and further progression of disease. Care plans should be realistic, minimally invasive, and tailored to the patient’s long-term disease trajectory. The clinician must pay attention to verbal and nonverbal communication as individuals with AD may have difficulty expressing discomfort or fear. Effective communication with the patient and caregiver may include shorter appointment times, gentle and patient conversations, and the tell-show-do technique.35 Reduced cognition and dexterity may mean patients cannot recognize or report pain.

Oral health professionals should recommend specific aids, such as adaptive toothbrush handles or electric brushes, for caregivers.22 Caregivers can then be educated on techniques to help the patient with daily oral hygiene. Table 2 provides practice recommendations for partnering with caregivers of patients with AD.

By creating a strong partnership with the caregiver, oral health professionals can better address the complex oral health needs of patients with AD. Providing caregivers with the knowledge, tools, and clear communication will improve quality of care and quality of life for the patient.

By creating a strong partnership with the caregiver, oral health professionals can better address the complex oral health needs of patients with AD. Providing caregivers with the knowledge, tools, and clear communication will improve quality of care and quality of life for the patient.

Conclusions

AD presents significant challenges not only for affected individuals but also for their caregivers. As the disease progresses, the need for comprehensive and personalized care becomes even more crucial. Dental health, often overlooked, plays a vital role in the overall health and quality of life of patients with AD. By understanding the specific oral health challenges these individuals face, oral health professionals can develop tailored, evidence-based strategies to address these concerns effectively.

Collaboration with caregivers is essential in ensuring proper care, as they are often directly involved in assisting with oral hygiene routines. By focusing on the unique needs of patients with AD and using a team-based approach, oral health professionals can help enhance the comfort, health, and dignity of individuals living with AD. Dental hygienists are in a unique position to advocate for and implement care strategies that preserve dignity and quality of life.

References

- Meiner SE, Yeager JJ. Gerontologic Nursing. 6th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2019.

- Touhy T, Jett K. Toward Healthy Aging. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2023.

- Alzheimer’s Association. Help & Support. Available at alz.org. Accessed December 3, 2025.

- Touhy T, Jett K. Ebersole and Hess’ Gerontological Nursing and Healthy Aging. 6th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2022.

- Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, John V, Loewenstein D. Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:530–538.

- Alzheimer’s Society. About Dementia. Available at alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia. Accessed December 3, 2025.

- National Institute on Aging. Caregiving. Available at nia.nih.gov/health/caregiving. Accessed December 3, 2025.

- Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2369–2379.

- Saeed A, Lopez O, Cohen A, Reis S. Cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease: The heart-brain axis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:9

- Petrovitch H, White L, Masaki KH, et al. Influence of myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass surgery, and stroke on cognitive impairment in late life. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:1017–1021.

- Bunch TJ, Weiss J P, Crandall BG, et al. Atrial fibrillation is independently associated with senile, vascular, and Alzheimer’s dementia. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:433–437.

- Janson J, Laedtke T, Parisi JE, O’Brien P, Petersen RC, Butler PC. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in alzheimer disease. Diabetes. 2004;53:474–481.

- Janson J, Laedtke T, Parisi JE, O’Brien P, Petersen RC, Butler PC. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes. 2004;53:474–481.

- Valderas JM, Starfield B, Sibbald B, Salisbury C, Roland M. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:357-363.

- Alzheimer’s Association. Healthy Brain Initiative Road Map. Available at alz.org/professionals/public-health/models-frameworks/hbi-road-map. Accessed December 3, 2025.

- National Institutes of Health. Periodontal Disease in Adults (Age 30 or Older). Available at nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/periodontal-disease/adults. Accessed December 3, 2025.

- Dioguardi M, Crincoli V, Laino L, et al. The role of periodontitis and periodontal bacteria in the onset and progression of alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2020;9:495.

- Gehrig JS, Shin DE. Foundations of Periodontics for the Dental Hygienist. 6th ed. New York: Lippincott; 2024.

- Nicholson JS, Landry KS. Oral dysbiosis and neurodegenerative diseases: correlations and potential causations. Microorganisms. 2022; 10:1326.

- Borsa L, Dubois M, Sacco G, Lupi L. Analysis the link between periodontal diseases and alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:9312.

- Brogden KA, Guthmiller JM, eds. Polymicrobial Diseases. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2002.

- Gao SS, Chu CH, Young FYF. Oral health and care for elderly people with alzheimer’s disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5713.

- Soni J, Sinha S, Pandey R. Understanding bacterial pathogenicity: a closer look at the journey of harmful microbes. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1370818.

- Miklossy J, McGeer PL. Common mechanisms involved in Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes: a key role of chronic bacterial infection and inflammation. Aging (Albany NY). 2016;8:575-588.

- Wu H, Qiu W, Zhu X, et al. The periodontal pathogen fusobacterium nucleatum exacerbates alzheimer’s pathogenesis via specific pathways. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:912709.

- Sparks Stein P, Steffen MJ, Smith C, et al. Serum antibodies to periodontal pathogens are a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:196-203.

- Hamza SA, Asif S, Bokhari SA. Oral health of individuals with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: A review. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2021;25:96-101.

- Gao SS, Chen KJ, Duangthip D, Lo ECM, Chu CH. The oral health status of Chinese elderly people with and without dementia: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1913.

- Ming Y, Hsu SW, Yen YY, Lan SJ. Association of oral health-related quality of life and Alzheimer disease: A systematic review. J Prosthet Dent. 2020;124:168-175.

- Holt E. Oral care for patients with Alzheimer disease. Decisions in Dentistry. 2023;9(4):30-33.

- Elsig F, Schimmel M, Duvernay E, et al. Tooth loss, chewing efficiency and cognitive impairment in geriatric patients. Gerodontology. 2015;32:149-56

- Alessandro GD, Costi T, Alkhamis N, Bagattoni S, Sadotti A, Piana G. Oral health status in Alzheimer’s disease patients: A descriptive study in an Italian population. J Contemp Dent Prac. 2018;19:48-489.

- Hugo FN, Hilgert JB, Bertuzzi D, Padilha DM, De Marchi RJ. Oral health behaviour and socio-demographic profile of subjects with Alzheimer’s disease as reported by their family caregivers. Gerodontology. 2007;24:36-40.

- Healthy People 2030. Social Determinants of Health. Available at https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health. Accessed December 3, 2025.

- Chavez EM, Wong LM, Subar P, Young DA, Wong A. Dental care for geriatric and special needs populations. Dent Clin N Am. 2018;62:245-267.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January/February 2026; 24(1):36-39