Bringing Social Determinants of Health Into the Dental Hygiene Diagnosis

Knowledge of these social determinants is essential to providing accurate dental hygiene diagnoses and delivering truly person-centered care.

This course was published in the January/February 2026 issue and expires February 2029. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 558

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define social determinants of health.

- Discuss the screening tools to identify individuals with social determinants of health conditions.

- Explain how to refer individuals presenting to the dental hygiene practice for further care to foster optimal outcomes.

The dental hygiene diagnosis (DHDx) was introduced to the dental hygiene process of care in the early 1990s.1 According to the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA), DHDx is “the identification of an individual’s health behaviors, attitudes, and oral health care needs for which a dental hygienist is educationally qualified and licensed to provide.”2 Dental hygienists use assessment data to determine the DHDx and care planning to support improved health outcomes.

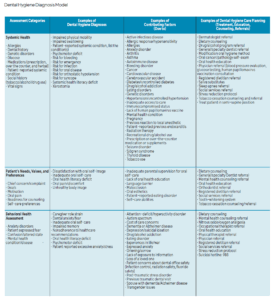

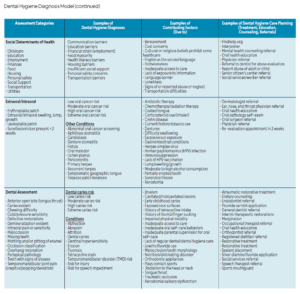

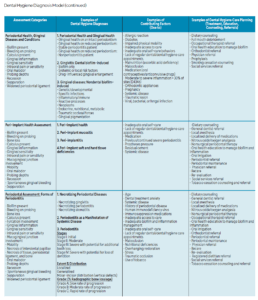

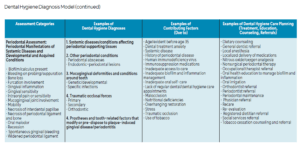

In 2015, a model for creating the DHDx was introduced composed of four main categories: assessment, examples of dental hygiene diagnoses, examples of contributing factors, and examples of dental hygiene care planning including treatment, education, counseling and referrals.3 This model was updated in 2018 to include the current periodontal classification.4 Today, the emphasis is on social determinants of health (SDOH), which have been incorporated into the Dental Hygiene Diagnosis Model.

Healthy People 2030 defined SDOH as “the conditions in the environment where people are born, live, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality of life outcomes and risks.”5 Additionally, Healthy People 2030 included objectives based on SDOH needs in the domains of economics, education, healthcare, neighborhoods and communities. While progress is being made in some of these areas, other areas are declining, such as dwindling community connections. Many individuals do not have the social support of friends and family to share health concerns, which may increase physical and mental health problems.6

Food insecurity and hunger are also growing issues. Adequate access to nutritionally sound foods improves health outcomes for both adults and children and can improve school performance in children.7 Dental hygienists need to be aware of the correlation between a lack of healthy foods and an increase in unmet dental care needs.8 Food deserts, areas where residents lack access to healthy, affordable food, are disproportionately located in communities of low-income, minority populations.9

Individuals may present every day in practice that fit these descriptions of unmet SDOH needs and yet clinicians may be unaware. Associating SDOH with general health and oral disease is key for recognizing unmet needs and improving health outcomes.

Unmet Needs

Dental hygienists understand how periodontal diseases can negatively impact systemic conditions such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, and obesity.10 Additionally, diabetes has a bidirectional relationship with periodontal diseases, meaning each condition can increase the severity of the other. Patients with SDOH are at increased risk for these systemic conditions.

Patients with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to develop type 2 diabetes and have more complications related to the disease. The incidence of diabetes and mortality rate are higher among individuals who have not completed high school. Lack of employment increases the risk of developing both prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. For those who have unstable housing, eating nutritionally, getting adequate exercise, and gaining access to medications and testing supplies needed for those with diabetes can be difficult.11

Many SDOH factors are related to cardiovascular disease and obesity.12,13 Socioeconomic status, lack of adequate employment, neighborhoods that are unsafe for outdoor exercise, limited access to grocery stores and healthy food, lower education levels, and lack of social support systems, all increase the risk of developing and dying from cardiovascular diseases.12 Further, individuals with higher SDOH needs have a higher prevalence of obesity.13

Periodontal diseases are not the only oral maladies to be impacted by unmet SDOH needs. Patients with oral cancer who have unmet SDOH experience poorer health outcomes. They present with more advanced cancer at the time of diagnosis, are less likely to have surgery, and experience poorer survival rates.14,15

Dental caries risk and prevalence are higher in patients with food insecurity, lower socioeconomic status, and lower oral health literacy.8,16 Children of non-English speaking parents are less likely to understand the need for regular dental visits and preventive measures and are more likely to have limited access to dental insurance. These SDOH factors increase the burden of disease in these individuals.16

Clinicians might not know if a patient has SDOH needs unless they ask. The screening process can be quick and easy with a short questionnaire, and then the DHDx related to SDOH unmet needs can be determined.

Diagnostic Categories

SDOH has been incorporated into the Dental Hygiene Diagnosis Model to reflect examples of experiences that may impact oral healthcare. The diagnostic categories are derived from SDOH screening tools that examine various SDOH domains, including Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool,17,the Social Needs Screening Tool,18 the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patient Assets, Risks, and Experience tool,19 and the Health Begins tool.20 Each tool is briefly described to help clinicians identify which instrument might be most appropriate for their dental hygiene practice setting.

The Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool includes 10 items categorized into five domains: housing instability, food insecurity, transportation problems, utility help needs, and interpersonal safety. Supplemental domains within this tool address financial strain, employment, family and community support, education, physical activity, substance use, mental health, and disabilities. The tool includes 26 items and is meant to be used for individuals, parents or caregivers, and clinicians.17

The Social Needs Screening Tool was developed by the American Academy of Family Physicians to improve health equity in every community. This tool includes 15 items across 10 domains such as housing, food, transportation, utilities, childcare, employment, education, finances, personal safety, and assistance.18

The Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patient Assets, Risks, and Experiences tool was created by the National Association of Community Health Centers. This 21-item tool addresses five SDOH domains: personal characteristics, family and home, money and resources, social and emotional health, and optional additional questions.19

The Health Begins instrument captures social and behavioral domains that impact the opportunity to have a safe, healthy place to live, work, eat, sleep, learn and play. Fourteen domains are included in the 15-item screening tool including education, employment, social connection and isolation, physical activity, immigration, financial strain, housing insecurity, food insecurity, dietary pattern, transportation, exposure to violence, stress, and civic engagement.20

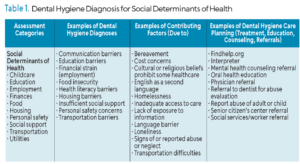

Based on the domains identified in the four screening tools described above, the updated Dental Hygiene Diagnosis Model (Table 1) examines SDOH domains including community/social support, cultural influences, economic stability, educational, food security, health care system, language, and physical/environment/safety. Examples of DHDx might include, but are not limited to communication barriers, education barriers, financial strain (employment), food insecurity, health literacy barriers, housing barriers, insufficient social support, personal safety concerns, and transportation barriers.

Contributing factors leading to these diagnoses relate to bereavement, cost concerns, cultural or religious beliefs, English as a second language, homelessness, inadequate access to care, loneliness, signs of or reported abuse or neglect, and transportation difficulties. Once the SDOH DHDx is determined, the care plan might include the need for an interpreter or personalized oral health education. Referrals could be indicated for mental health counseling, physician care, dentists for abuse evaluation, senior citizen’s center, or social services. In cases of suspected or reported abuse, referral to the appropriate local or state agency is warranted.

Contributing factors leading to these diagnoses relate to bereavement, cost concerns, cultural or religious beliefs, English as a second language, homelessness, inadequate access to care, loneliness, signs of or reported abuse or neglect, and transportation difficulties. Once the SDOH DHDx is determined, the care plan might include the need for an interpreter or personalized oral health education. Referrals could be indicated for mental health counseling, physician care, dentists for abuse evaluation, senior citizen’s center, or social services. In cases of suspected or reported abuse, referral to the appropriate local or state agency is warranted.

Community Resources

The national findhelp.org website provides resources for SDOH needs.21 On findhelp.org, local resources can be found for food, housing, goods, transit, health, money, care, education, work, and legal services. Oral health professionals can identify local resources within their communities and create a handout that is readily available and relevant for their practice.

Person-Centered Care

The following case studies provide an opportunity to assess individuals for SDOH and determine related DHDx. Each case represents different types of SDOH that may present in the dental office.

Case Study A. Colette is a 35-year-old single mom with two preschool-age children. She struggles to feed her children and to find safe childcare for them. Currently, she is employed full-time at a minimum wage job that provides no health benefits. Her children are on state Medicaid health and dental plans, but there is a wait list to find a dental provider willing to accept Medicaid. When the dental hygienist takes Colette’s blood pressure, the results are 159/90 mmHg.

Per Table 1, the SDOH DHDx relevant for this case are food insecurity, insufficient social support (childcare), and financial strain (insufficient wages and no health benefits). By using the findhelp.org website and her zip code, Colette and/or the dental hygienist can search for local resources in the categories of childcare, employment, finances, food, and social support.

Case Study B. Carl is a full-time college student with anxiety and depression who does not have a stable place to live. He is not working and is without family support. He has no medical or dental insurance. When he is able, he accesses the food pantry and clothes closet at his college. He tried to schedule a dental appointment because he has a toothache, but he has no money to pay for it. He ends up in the emergency department for help with the pain. The dental hygienist employed by the hospital evaluates the patient and determines there is a dental abscess with suppuration, and realizes the patient is at risk for a tooth extraction and further infection.

The SDOH DHDx for Carl are financial strain, food insecurity, housing barriers, personal safety concerns, and insufficient social support. Referrals to the findhelp.org website, a mental health counselor, a local dentist or dental therapist, and social services are appropriate.

Although the cases presented above focused specifically on SDOH needs, the DHDx Model offers a comprehensive list of DHDx in multiple assessment categories . The individuals in the previous cases would also have DHDx in other categories. For example, in Case A, Colette would also have a DHDx of risk for emergency due to uncontrolled hypertension, requiring a referral to a physician for evaluation. In Case B, Carl would have a DHDx of patient reported excessive anxiety and depression, requiring the care plan to include stress reduction protocols along with the referrals.

Importance of Addressing Social Determinants of Health

Integrating SDOH into dental hygiene practice is a critical step toward providing comprehensive and person-centered care. Understanding and addressing SDOH allows dental hygienists to identify barriers to optimal oral health, develop targeted interventions, and connect patients with essential community resources. The practical implementation of SDOH assessment and diagnosis in dental hygiene practice is not only feasible but also essential for fostering improved health outcomes.

A key strategy for incorporating SDOH into routine dental hygiene care is the integration of SDOH-related questions into the health history assessment. By adding a brief but effective screening tool to health history forms, dental hygienists can systematically identify individuals with unmet social needs that impact their general and oral health. This screening process does not need to be time-consuming; many of the validated tools discussed previously contain concise questions that can be quickly reviewed by the dental team.

The successful implementation of SDOH screening requires collaboration among the entire dental team, including dental assistants, front office staff, and billing personnel. Office staff can assist individuals in completing the screening tools, while dental hygienists review responses and determine appropriate DHDx based on SDOH factors. Training the entire dental team on the importance of SDOH and how unmet needs influence oral health outcomes is vital to ensure consistency in implementation. Staff education sessions can highlight the connections between SDOH and common oral health conditions.

Once SDOH-related barriers are identified, dental hygienists can work to develop individualized care plans that include tailored education, referrals, and support services. Utilizing readily available community resources enables dental professionals to connect those in need with food assistance programs, transportation services, housing support, and mental health resources. Maintaining a list of local resources available in multiple languages ensures the practice meets its patients’ needs.

Financial concerns are a common barrier to accessing dental care. The dental billing coordinator can play a significant role in assisting individuals with understanding their insurance benefits, exploring financial assistance programs, and setting up payment plans when necessary.

Conclusion

By making small but impactful changes in how social factors are assessed and addressed, oral health professionals can bridge the gap between systemic and oral healthcare. Implementing SDOH screening and intervention are not just theoretical concepts, they are a practical and essential component of modern dental hygiene practice that ensures all individuals receive the comprehensive, person-centered care they deserve.

References

- Gurenlian JR. Diagnostic decision making . In: Woodall I, ed. Comprehensive Dental Hygiene Care. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993:361–70.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at adha.org/education-resources/standards/. Accessed December 1, 2025.

- Swigart DJ, Gurenlian JR. Implementing dental hygiene diagnosis into practice. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2015;13(9):56-59.

- Gurenlian JR, Swigart DJ. Components of dental hygiene diagnosis. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2018;16(12):36-39.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030. Available at https://odphp.health.gov/ healthypeople/ priority-areas/social-determinants-health. Accessed December 1, 2025.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030, Health Communication. Available at https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/health-communication/increase-proportion-adults-who-talk-friends-or-family-about-their-health-hchit-04. Accessed December 1, 2025.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030, Economic Stability. Available at: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/economic-stability. Accessed December 1, 2025.

- Wiener RC, Sambamoorthi U, Shen C, Alwhaibi M, Findley P. Food security and unmet dental care needs in adults in the United States. J Dent Hyg. 2018;92:14-22.

- Beaulac J, Kristjansson E, Cummins S. A systematic review of food deserts, 1966-2007. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:A105.

- Chapple I, Genco R. Diabetes and periodontal diseases: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on periodontitis and systematic diseases. J Periodontol. 2013;84;S106-S112.

- Hill-Briggs F, Adler NE, Berkowitz SA, et al. Social determinants of health and diabetes: A scientific review. Diabetes Care. 2020;44:258–279.

- Javed Z, Haisum Maqsood M, Yahya T, et al. Race, racism, and cardiovascular health: Applying a social determinants of health framework to racial/ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022;15:e007917.

- Javed Z, Valero-Elizondo J, Maqsood MH, et al. Social determinants of health and obesity: Findings from a national study of US adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2022;30(2):491-502.

- Agarwal P, Agrawal RR, Jones EA, Devaiah AK. Social determinants of health and oral cavity cancer treatment and survival: A competing risk analysis. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:2160-2165.

- Tellez M, Zini A, Estupiñan-Day S. Social determinants and oral health: an update. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2014;1:148–152.

- Ramos-Gomez F, Kinsler JJ. Addressing social determinants of oral health, structural racism and discrimination and intersectionality among immigrant and non-English speaking Hispanics in the United States. J Public Health Dent. 2022;82(Suppl 1):133-139.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The accountable health communities health-related social needs screening tool. Available at: cms.gov/priorities/ innovation/files/worksheets/ahcm-screeningtool.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2025.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Social Needs Screening Tool. Available at aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/ patient_care/everyone_project/hops19-physician-form0sdoh.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2025.

- National Association of Community Health Centers Inc. PRAPARE: Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Rsks and Experiences. Available at https://prapare.org/ wp-content/uploads/2024/04/PRAPARE-English.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2025.

- Manchanda R, Gottlieb L. Upstream risks screening tool and guide V2.6. Health Begins. Available at medchi.org/Portals/18/Files/Practice%20Services/SDoH%20Screening%20Tool.pdf?ver=2023-08-10-131750-180. Accessed December 1, 2025.

- Findhelp. Help Is Available in Your Neighborhood. Available at: findhelp.org. Accessed December 1, 2025.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January/February 2026; 24(1):32-35