This colored scanning electron micrograph shows dental biofilm on a human tooth.

DAVID SCHARF / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

This colored scanning electron micrograph shows dental biofilm on a human tooth.

DAVID SCHARF / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Battling Biofilm

Improving oral health professionals’ understanding of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of biofilm associated diseases is key to their successful prevention and treatment.

TINA CARVALHO, UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA / NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

With the growing rate of antimicrobial resistance and the increasing cost of health care in the United States, an improved understanding of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of biofilm-associated diseases has become a major focus in medical and oral health care. Periodontal diseases and dental caries are two of the most commonly encountered oral diseases, and additional research is needed to better characterize and develop treatment modalities to reduce their destructive nature. Plaque biofilm is a major risk factor in the development and progression of both disease states. Over time, if left untreated, destruction of the tooth and its supporting structures can occur, leading to tooth loss. Periodontal maintenance with periodic recare intervals is critical for the prevention of plaque/biofilm-related diseases and for reinforcing patient self-care.

HOW DOES THE SUBGINGIVAL BIOFILM THAT FORMS FOLLOWING PERIODONTAL MAINTENANCE DIFFER FROM BIOFILM FOUND ELSEWHERE IN THE ORAL CAVITY?

Periodontal maintenance is aimed at minimizing the recurrence or severity of disease in patients previously treated for periodontal or peri-implant diseases. Dental hygienists perform several therapies during the maintenance visit, which directly or indirectly impact the composition of supra- and subgingival biofilm in diseased and nondiseased sites. Treatment involves mechanical removal of subgingival and supragingival biofilm/calculus with hand and/or ultrasonic instruments followed by behavioral modification strategies as needed. Furthermore, systemic antibiotics, local antimicrobials, and surgical interventions may also be necessary for disease management.1

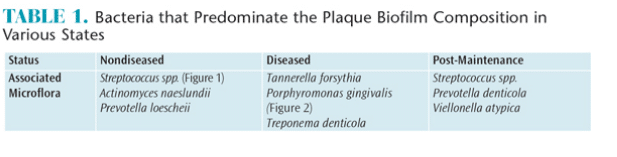

Healthy gingival sulci have a different microbial composition than the flora associated with periodontal diseases. Supragingival biofilm is dominated by aerobic Gram-positive cocci and short rods, which are classified as commensal microorganisms. Subgingival biofilm is predominated by anaerobic Gram-negative rods and filaments, as well as spirochetes, any of which can be involved in the etiopathogenesis of periodontal diseases (Table 1). Individuals with periodontal diseases have subgingival biofilm and may have calculus on the teeth proximate to their periodontal pockets. These infections elicit several reactions from the host’s immune system. A periodontal infection combined with inflammation can cause clinical attachment loss.

The gold standard for periodontal treatment is thorough subgingival scaling and root planing, which may require periodontal surgery to ensure adequate access. When detecting calculus, a dental endoscope may be more effective than a tactile explorer.2 Following thorough debridement of diseased periodontal pockets, the population of Gram-negative bacteria is reduced, which enables the number of Gram-positive bacteria to increase within

A. DOWSETT, PUBLIC HEALTH ENGLAND / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

24 hours to 48 hours post-treatment.3 The use of subantimicrobial tetracycline-family drugs that inhibit proteolytic enzymes in gingival tissue may enhance the outcomes of scaling and root planing—at least in the short term.4 According to a recent systematic review that included meta-analyses, other therapies, such as systemic antimicrobials, chlorhexidine chips, and photodynamic therapy with a diode laser, may also be effective adjuncts to scaling and root planing.5

DO CHANGES IN BIOFILM COMPOSITION IMPACT RECARE FREQUENCY?

Periodic maintenance and recare visits form the foundation of a meaningful long-term effort to prevent or limit subsequent attachment losses.6 The duration of initial and delayed healing responses to periodontal therapy depend on the nature and extent of the disease, modality of therapy, and type of care provided during the healing stage.1

Previous research has illustrated that in patients with chronic generalized mild to severe chronic periodontitis, improvements in periodontal health (decreased bleeding on probing and pocket depths and gains of clinical attachment) were noted during the initial 4 weeks after a single episode of scaling and root planing.7 Studies conducted on bacterial repopulation suggest that it takes several months for pathogenic bacteria to reestablish themselves.8 Improvements in clinical and microbiological parameters following periodontal treatment support a 3-month interval between periodontal maintenance visits. On one hand, research suggests that longer intervals (eg, 6 months) may be appropriate for patients who are able to maintain adequate plaque control, while other patients may need more frequent periodontal maintenance visits.7

A multicenter, split-mouth study assessed several putative periodontal pathogens associated with chronic periodontitis and their responses to traditional periodontal therapy at several time points. Numbers and proportions of detectable pathogens with the exception of Porphyromonas gingivalis exhibited temporal responses. Other pathogens exhibited an initial decrease immediately following therapy, a rise in proportions in 1 month to 3 months post-therapy, and a spontaneous decline in the absence of therapy over the 3-month to 12-month period.9 Taken together, putative periodontal pathogens show differences in susceptibility to periodontal therapy, suggesting that maintenance care intervals need to be customized based on the results of frequent monitoring.

Individuals diagnosed with aggressive periodontitis generally require a greater frequency in periodic maintenance and recare visits. Rapid attachment loss coupled with low levels of biofilm deposits present other clinical challenges in preventing disease progression and may require an interdisciplinary approach with other dental specialists. The diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis is often made at an advanced stage of the disease, which results in clinicians treating severely compromised teeth. Consequently after nonsurgical therapy, residual pockets will remain. Pathogenic microorganisms like Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans have been shown to invade the pocket epithelium and remain persistent. Hence, the conventional treatment of aggressive periodontitis may include surgical removal of the pocket epithelium and administration of systemic antibiotics.10 More recently, nonsurgical therapy with adjunct photodynamic therapy using lasers has been found to be effective in eliminating Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans.11 Lasers may be as effective as surgical therapy in treating aggressive periodontitis.12 More research is needed, however, to substantiate these adjunctive therapies.

WHAT IS THE OBJECTIVE OF PERIODONTAL THERAPY?

Removal of calculus and biofilm is accomplished using hand or ultrasonic instrumentation, or a combination of both. The objective of periodontal therapy, while difficult to attain, is complete removal of nonmicroscopic calculus and biofilm. However, a significant reduction of pathological bacteria in periodontal pockets may permit repopulation by nonpathogenic microbes. This may, in turn, down-modulate the immune response, thereby limiting or eliminating cytokines that facilitate destruction of the periodontium.

Evidence suggests that nonsurgical treatment results measuring clinical and microbiological periodontal conditions for chronic periodontitis are similar for both hand and ultrasonic scaling at 6 months post-operatively.13 For single-rooted teeth, a comparable effectiveness between manual and ultrasonic instrumentation has been shown for the treatment of chronic periodontitis.13 Some research has found ultrasonic instrumentation to be superior in the treatment of Class II and III furcations; however, scaling and root planing remains more effective for improving clinical attachment loss.9 Notwithstanding these results, clinicians need to keep in mind that periodontal maintenance should be customized for every patient.

WHAT IS THE HOST RESPONSE TO DEEP POCKET BIOFILM AND PATHOGENS?

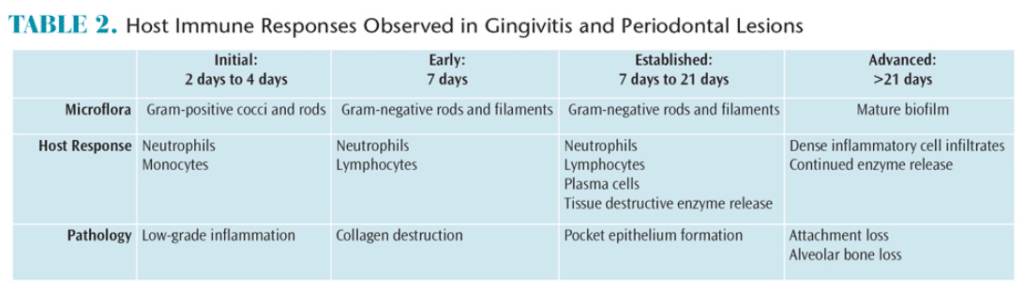

Periodontal diseases result from complex interactions between subgingival biofilms and hosts’ immune systems. In gingivitis, the inflammatory lesion is largely confined to the gingiva. In periodontitis, however, the inflammatory processes extend to affect the periodontal ligament and the alveolar bone. The net result of these inflammatory changes is the subsequent breakdown of the periodontal ligament fibers and gingival soft tissues, resulting in loss of attachment and bone resorption. Table 2 provides an overview of the clinical responses to biofilm and host immunity.

WHEN DO BACTERIA INVADE THE TISSUES OF PERIODONTAL POCKETS?

A clear understanding of the periodontium and its related structures is an important foundation for interpreting the advanced stages and characteristics of periodontal disease. These structures withstand the physiological forces of mastication and defend against foreign invaders, such as bacteria. Over time, inadequate oral hygiene measures can result in several microbial and pathologic challenges to the periodontium.

Studies have illustrated the development and progression of gingivitis to periodontal disease. A landmark study demonstrated that subjects who refrained from performing oral hygiene measures developed gingivitis within 7 days to 21 days.14 At the 7-day point, the composition of the biofilm bacteria shifted from aerobic Gram-positive species to more virulent Gram-negative organisms. Although reversible, this microbial shift can result in bacterial invasion of the soft tissue, an increase in the body’s immune response, and bleeding on probing, which will lead to periodontitis if left untreated.15–17

HOW IS THE PERIODONTAL INFECTION RESOLVED?

Treatment of aggressive periodontitis should include the surgical removal of the pocket epithelium and administration of systemic antibiotics because of the potential for tissue invasion by Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans.9 Nonsurgical therapy with antimicrobial photodynamic therapy using lasers has been found to be effective in eliminating Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans,11 and this therapy can be performed by dental hygienists in states where practice acts allow. Following successful periodontal therapy, a cascade of biochemical-based responses occur that result in a small amount of new periodontal attachment as part of the healing response. More important is that the inflammation is reduced, thereby facilitating anatomic site stability if recurrent infection is prevented. Successfully treated sulci repopulate with bacteria typical of periodontal health.18

CONCLUSION

Oral biofilm significantly impacts the initiation and progression of periodontal diseases and its repeated removal is paramount to improving and maintaining oral health. Dental hygienists play a critical role in providing effective removal of biofilm both supra- and subgingivally. Dental hygienists also help patients develop optimal self-care regimens. It should be noted that periodontal maintenance intervals are adjustable and depend on the results of frequent reassessments of oral health status in the context of self-care and previously provided clinical therapies.

REFERENCES

- Ramjford SP. Maintenance care for treated periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:433–437.

- Osborn JB, Lenton PA, Lunos SA, Blue CM. Endoscopic vs. tactile evaluation of subgingival calculus. J Dent Hyg. 2014;88:229–236.

- Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Teles R, et al. Effect of periodontal therapy on the subgingival microbiota over a 2-year monitoring period. I. Overall effect and kinetics of change. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:771–780.

- Caton J, Proye M, Polson A. Maintenance of healed periodontal pockets after a single episode of root planing. J Periodontol. 1981;53:420–424.

- Smiley CJ, Tracy SL, Abt E, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the nonsurgical treatment of chronic periodontitis by means of scaling and root planing with or without adjuncts. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146:508–524.

- Shallhorn RG, Snider LE. Periodontal maintenance therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 1981;103:227–231.

- Caton JG, Ciancio SG, Blieden TM, et al. Treatment with subantimicrobial dose doxycycline improves the efficacy of scaling and root planing in patients with adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:521–532.

- Lowenguth RA, Chin I, Caton JG, et al. Evaluation of periodontal treatments using controlled-release tetracycline fibers: microbiological response. J Periodontol. 1995;66:700–707.

- Teughels W, Dhondt R, Dekeyser C, Quirynen M. Treatment of aggressive periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2014;65:107–133.

- Novaes AB Jr, Schwartz-Filho HO, de Oliveira RR, Feres M, Sato S, Figueiredo LC. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the non-surgical treatment of aggressive periodontitis: microbiological profile. Lasers Med Sci. 2012;27:389–395.

- Mummolo S, Marchetti E, Di Martino S, Scorzetti L, Marzo G. Aggressive periodontitis: laser Nd:YAG treatment versus conventional surgical therapy. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2008;9:88–92.

- Ioannou I, Dimitriadis N, Papadimitriou K, Sakellari D, Vouros I, Konstantinidis A. Hand instrumentation versus ultrasonic debridement in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: a randomized clinical and microbiological trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:132–141.

- Löe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177.

- Cobb CM. Clinical significance of non-surgical periodontal therapy: an evidence-based perspective of scaling and root planing. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(Suppl 2):6–16.

- Saglie R, Newman MG, Carranza FA Jr, Pattison GL. Bacterial invasion of gingiva advanced periodontitis in humans. J Periodontol. 1982;53:217–222.

- Schroeder HE, Page RC. Pathogenesis of inflammatory periodontal disease. A summary of current work. Lab Invest. 1976;33:235–249.

- Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Dibart S, Smith C, Kent RL Jr, Socransky SS. The effect of SRP on the clinical and microbiological parameters of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:324–334.

- Listgarten MA. The structure of dental plaque. Periodontol 2000. 1994;5:52–65.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2015;13(11):44,46,48–49.