Detecting Mental Health and Substance Use Risks

The dental practice is a prudent setting to screen for these common issues faced by many Americans.

This course was published in the November/December 2025 issue and expires December 2028. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 157

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the bidirectional relationships between oral health, mental health, and substance use.

- Explain the components of the screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment.

- Discuss evidence-based screening tools to identify patients at risk for substance use disorders or mental health conditions and facilitate appropriate referrals for treatment.

Oral health is an integral part of overall health. The 2000 Surgeon General’s Report, “Oral Health in America,” reported associations between oral diseases and healthcare access.1 In addition, in 2003, the Surgeon General recommended addressing these issues by increasing the oral health workforce, supporting collaboration between dental and medical providers, and improving access to care.2

Data show that about 86% of American adults had an annual dental visit in 2019-2020, with about 65% of those between the ages of 18 and 64.3,4 As awareness of the connection between dentistry and medicine grows, dental practices will be seen as a source of primary care.5,6

Oral health professionals frequently assess essential health awareness and understanding; however, important health issues, including substance use and mental health, may be overlooked. Oral and mental health have a bidirectional relationship.7 Baniasadi et al8 explain how oral health determinants are associated with poor oral health-related quality of life. Additionally, pharmaceutical management of depression and anxiety often involves medication that can cause xerostomia.7

Mental Health and Substance Use

Poor oral health can affect how individuals view themselves, which contributes to general anxiety and depression. Poor oral health also contributes to an increased risk of memory loss, dementia, and Alzheimer disease.7 Mental illness is among the most common health conditions in the United States, with nearly one in four US adults and one in seven adolescents presenting with a mental health condition. This accounts for about 15% of the global burden of disease.7,9,10 As awareness of these associations grows, oral health professionals should expand their practice to account for general habits and risk factors.

Substance misuse is another important area of concern, as habitual substance use and mental health conditions are detrimental to long-term oral health.7,8,11-13 A systematic review and meta-analysis revealed relationships between substance use and tooth loss, periodontal diseases, and high decay-missing-filled index scores.14 Substance use disorders in adolescents is a growing problem.15 Some oral health professionals may be uncomfortable asking their patients about substance use; however, adults may support the idea. Surveys have shown that patients are amenable to receiving medical screenings chairside in the dental setting.12

Miller et al11 asked three substance use screening questions and had patients complete an opinion survey regarding attitudes about the acceptability of the screening and counseling by oral health professionals. Findings indicated that 25% of respondents had positive substance screening scores, indicating probable hazardous substance use and an increased risk of developing oral cancer. In general, most dental patients (typically > 75%) favored their oral health professionals’ inquiry and advice about substance use.11

Experts recommend developing programs to address this issue in the dental setting.14 Basic behavioral-based treatments may be implemented alongside dental care. Screening for oral health disease in substance use treatment settings could increase early detection of oral health problems and facilitate referral to dental services.14

Not all oral health professionals will be comfortable screening for substance misuse. In a survey of American oral health professionals, two-thirds noted they did not feel substance misuse screening was within their role as a healthcare provider.12 Increasing awareness about the use of screening tools and their ability to address systemic health is necessary to widening their use in the dental setting.

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment

Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) is a comprehensive approach for early intervention and treatment for individuals with substance use disorders.15-16 Screening tools for substance use and mental health issues are available to measure the presence, risk, or severity of disorders; they can be self-administered or conducted by a health professional.17,18

Screening assesses the severity of the problem and identifies the appropriate level of treatment, brief intervention emphasizes increasing awareness and motivation for behavior change, and referral to treatment provides access to specialty care for those at risk.15,16 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening during both routine preventive appointments and nonpreventive visits either electronically or face to face.16

While there is no widely accepted definition of brief intervention, these sessions can range from 5 to 60 minutes and typically include education and motivational interviewing. Referral involves referring the patient to a specialized provider and is considered successful if the patient completes the recommended treatment.16

Screening is the initial step; however, identifying a problem does not resolve the overarching issue. SBIRT is both a public health model and a set of procedures for detecting individuals at risk of substance use disorders and administering appropriate prevention, early intervention, or treatment referral.16 Action through either brief intervention or referral to treatment needs to take place to fully help patients. This framework can also be used to screen patients for mental health issues.

Providers must use basic behavior change techniques such as motivational interviewing. When used in medical settings, brief motivational interviewing after SBIRT screenings causes short-term improvements in patient health.15 While additional research is needed to understand the long-term effects, motivational interviewing can be used to help patients understand the ambivalence and motivations behind their decision making and goal setting.15

Successful implementation of SBIRT also requires that providers know where to find interprofessional collaborative partners.7 Oral health professionals should build professional relationships with local resources such as addiction professionals, social workers, counseling centers, or medical clinics.

Findhelp, or 211, is a resource that is available online or by phone in many areas of the US.19 Oral health professionals can enter their office’s zip code and it will provide opportunities that are available for financial assistance, food pantries, medical care, and other free or reduced-cost help. For suicide crisis, calling or texting 988 connects callers with mental health professionals. Available in English and Spanish, these resources are open to all individuals.

Screening Tools

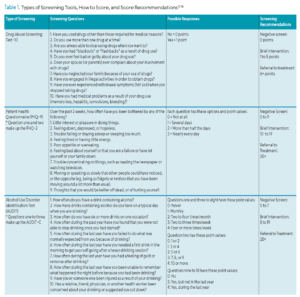

Ensuring that dental practices have an evidence-based system to facilitate screening will help create a seamless transition. Screening tools, such as the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10), Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT), and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9, can be self-administered or conducted via a 5-minute interview style (Table 1).17,18 Some scores may indicate monitoring and reassessment at a later date (brief intervention), further investigation (brief intervention), or intensive assessment (referral to treatment).

The DAST-10 is a 10-item self-report instrument condensed from 28 items. The DAST-10 was designed to provide a brief synopsis of drug abuse for adults and older youth. The first question in the DAST-10 asks, “Have you used drugs other than those required for medical reasons?” All 10 questions require a “yes” or “no” response.17 Each “yes’ answer receives 1 point (question 3 is the exception with a reverse score receiving 0 points), then, depending on the score, action may be required. A score of 1 to 2 suggests monitoring and assessing again later (brief intervention); 3 to 5 requires further investigation (brief intervention), and 9 to 10 leads to intensive assessment (referral to treatment).17,18

The AUDIT is a validated 10-question, Likert-style (0-4) screening tool that the World Health Organization developed to assess alcohol use. The first three questions make up the shortened version of the AUDIT called the AUDIT-C. Patients who respond to these three questions and whose score adds up to 3 or more points complete the full 10-question AUDIT. Screening results play a role in the recommendations; for example, a score of 15 or more is considered harmful alcohol use and may require referral to treatment.17

When brief intervention is necessary, the clinician just asks patients about their substance use. Motivational interviewing could also be used to determine their readiness to quit, the consequences of their use, and support for setting small, reasonable goals. Referral to treatment would require connecting with a specialized treatment program or professional in the area. Some providers give a counseling referral to any positive screening on the DAST or AUDIT to provide resources tailored specifically to the patient.17

The third screening tool is the PHQ-9, a nine-item, validated multipurpose screening tool for diagnosing, monitoring, and measuring the severity of depression.18 The first two questions encompass the short version called the PHQ-2. The first two questions are: “Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?” and “Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?” The options for both questions are 0 days (0 points), 1 or more days (1 point), 2 or more days (2 points), and 3 or more days (3 points). Patients who respond to these two questions and receive a score of three or more should complete the full PHQ-9. The results of the screening guide treatment decisions. A score of 10 to 14 requires support, education, and follow-up (brief intervention). A score of 14 or higher may require antidepressants or psychotherapy (referral to treatment).18 The referral would require connecting with a mental health provider.

Conclusion

While many studies discuss the effectiveness of SBIRT, barriers to implementation persist.20 Long-term data are not available showing that brief intervention is successful. Future studies, ongoing supervision, and support are still needed for successful implementation.20 Additional training for providers and quality assurance should be implemented for future success.

References

- Oral Health in America: a Report of the Surgeon General. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2000 Sep;28:685-695.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. A National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health. Available at ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47472. Accessed October 14, 2025.

- Cha AE, Cohen RA. Dental care utilization among adults aged 18-64: United States, 2019 and 2020. NCHS Data Brief. 2022;(435).

- Fellows JL, Atchison KA, Chaffin J, Chavez EM, Tinanoff N. Oral health in America: Implications for dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2022;153:601-609.

- Prasad M, Manjunath C, Muirthy AK, Sampath A, Jaiswal S, Mohapatra A. Integration of oral health into primary health care: A systematic review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:1838–1845.

- Vujicic M, Israelson H, Antoon J, Kiesling R, Paumier T, Zust M. A profession in transition. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:118-121.

- Tantawi ME, Folayan MO, Oginni O, et al. Association between mental health, caries experience and gingival health of adolescents in suburban Nigeria. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21:223.

- Baniasadai K, Armoon B, Higgs P, et al. The association of oral health status and socio-economic determinants with oral health-related quality of life among the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2021;19:153-165.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Mental Health. Available at cdc.gov/mental-health/about/index.html. Accessed October 14, 2025.

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Adolescents. Available at who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health. Accessed October 14, 2025.

- Miller PM, Ravenel MC, Shealy AE, Thomas S. Alcohol screening in dental patients: The prevalence of hazardous drinking and patients’ attitudes about screening and advice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1692-1698.

- Parish CL, Pereyra MR, Pollack HA, et al. Screening for substance misuse in the dental care setting: findings from a nationally representative survey of dentists. Addiction. 2015;110:1516-1523.

- Rodriquez JL, Thakkar-Samtani M, Heaton LJ, Tranby EP, Tiwari T. Caries risk and social determinants of health: a big data report. J Am Dent Assoc. 2023;154:113-121.

- Yazdanian M, Armoon B, Noroozi A, et al. Dental caries and periodontal disease among people who use drugs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:44.

- Bourgault A, Etcher L. Integration of the screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment screening instrument into school nurse practice. J Sch Nurs. 2021;38:311-317.

- Ozechowski TJ, Becker SJ, Hogue A. SBIRT-A: Adapting SBIRT to maximize developmental fit for adolescents in primary care. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;62:28-37.

- Rockne WY, Quinn KC, James G, Cochran A. Identification of substance use disorders in burn patients using simple diagnostic screening tools (AUDIT/DAST-10). Burns. 2019;45:1182-1188.

- Levis B, Sun Y, He C, et al. Accuracy of the PHQ-2 alone and in combination with the PHQ-9 for screening to detect major depression. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;23:2290-2300.

- Findhelp. Find free or reduced-cost resources like food, housing, financial assistance, healthcare, and more. Available at findhelp.org. Accessed October 14, 2025.

- Vendetti J, Gmyrek A, Damon D, Singh M, McRee B, Del Boca F. Screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT): implementation barriers, facilitators and model migration. Addiction. 2017;112:23-33.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November/December 2025; 23(6):32-35.