Sickle Cell Disease in the Dental Chair

How a centuries-old genetic mutation drives life-threatening complications and the oral signs oral health professionals can’t afford to miss.

This course was published in the January/February 2026 issue and expires February 2029. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 149

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define sickle cell disease (SCD).

- Identify the oral manifest ations of SCD.

- Discuss appropriate dental treatment for patients with SCD.

Sickle-cell disease (SCD) refers to a group of genetic blood disorders that impact hemoglobin — an oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells (RBCs) — leading to multisystem morbidity and reduced life expectancy. One of the most common severe genetic disorders worldwide, SCD affects about 100,000 people in the United States.1,2 SCD occurs in approximately one out of every 365 Black or African American births and one out of every 16,300 Hispanic American births.2

While the disease can exist in people of all races and ethnicities, it is particularly common among those whose ancestry originates where malaria is or was common, including Sub-Saharan Africa, South America, the Caribbean, Central America, Saudi Arabia, India, and Mediterranean countries. 2,3 The prevalence of SCD is highest in Sub-Saharan Africa, with an estimated 230,000 affected children born each year compared to 2,600 and 1,300 affected births in North America and Europe.1,2

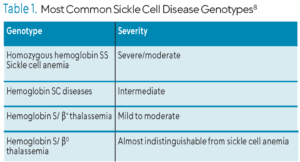

SCD is an umbrella term encompassing several forms of the disease with the most common being homozygous hemoglobin SS, also known as sickle cell anemia (SCA). Other forms of SCD are heterozygous conditions, commonly referred to as sickle cell trait (Table 1).1,3

The homozygous and heterozygous forms of SCD are starkly different diseases. SCA is severely disabling, while heterozygous forms are mostly benign. The mutation that causes SCD may confer partial protection against severe malaria.3-5 Compared to those with normal hemoglobin, individuals with sickle cell trait have a 50% to 90% reduction in parasite density.4

The homozygous and heterozygous forms of SCD are starkly different diseases. SCA is severely disabling, while heterozygous forms are mostly benign. The mutation that causes SCD may confer partial protection against severe malaria.3-5 Compared to those with normal hemoglobin, individuals with sickle cell trait have a 50% to 90% reduction in parasite density.4

Three pathophysiological processes are associated with SCD: sickle hemoglobin (HbS) polymerization, vaso-occlusion, and hemolysis-mediated endothelial dysfunction. The HbS mutation alters the physiology and rheology of RBCs.1,2,4-7 Vaso-occlusion can cause acute systemic vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC), or sickle cell crisis.1,7,8 Approximately 1% of patients have more than six VOC episodes per year while 39% have none.8 VOCs have no specific cause, but triggers may include infection, dehydration, extreme temperatures, hypoxia, stress, and menstruation.

VOC is characterized by intense pain and organ injury caused by hemolysis and sickling, leading to impaired blood flow. Hemolysis and sickling also increase plasma viscosity. Cycles of intermittent periods of reduced blood flow can lead to inflammatory stress and tissue injury, also known as ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ischemia-reperfusion injury can lead to chronic inflammation.1,7-11

Hemolytic anemia is precipitated by the rupture of RBCs, causing the release of hemoglobin into surrounding plasma. Free plasma hemoglobin may contribute to nitric oxide resistance, leading to vasoconstriction and impaired blood flow. Hemolytic anemia may cause symptoms in SCD patients including fatigue, anemia, and progressive vasculopathy.1,8,10

Systemic Complications

The chronic impact of hemolytic anemia and VOCs may result in systemic complications involving multiple organs, with symptoms appearing in the first 6 months of life.7-9

Cerebrovascular accidents are a major complication of SCD. Patients with SCD have a 200-fold increase in stroke risk compared to typical populations and once stroke has occurred, the risk of reoccurrence is more than 60%.1,8 SCA is also one of the most common causes of stroke in children due to vasculopathy. In 1 year, for every 100 patients with SCD, about one will experience his or her first stroke between the ages of 2 and 5, and 11% may have had a stroke by the age of 20.1,12 Vasculopathy may be detected early by transcranial doppler scanning.

Acute chest syndrome (ACS) is a lung injury that affects both children and adults with SCD. It is the leading cause of death and hospitalization among this patient population. ACS may appear radiographically as an alveolar pulmonary infiltrate involving at least one lung segment and presents with signs such as fever, chest pain, cough, or dyspnea.1,7,8,12,13 ACS is triggered by infection, fat embolism, vaso-occlusion of the pulmonary vasculature, and surgical procedures.1,7,13 Treatment may include broad-spectrum antibiotics, bronchodilators, oxygen, or mechanical ventilation.

Pulmonary hypertension occurs in approximately one third of patients with SCD and is a strong predictor of morbidity.1,12,13 Pulmonary pressures rise acutely during VOCs, and even more during acute chest syndrome. Risk factors for pulmonary hypertension include hypoxemia, sleep apnea, pulmonary thromboembolic disease, restrictive lung disease, left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction, severe anemia, and iron overload. Left heart disease may occur secondary to pulmonary hypertension and affects about 13% of adults with SCD.1,13 Patients with both diastolic dysfunction and pulmonary vascular disease are at an increased risk of death.1

The kidneys are particularly vulnerable to vaso-occlusive events, making renal damage almost unavoidable in SCD. Appearing early in life, renal dysfunction can cause impaired tubular function, limited urine output, and increased dehydration. Progressive renal injury may lead to chronic renal failure, most frequently occurring in the third or fourth decade of life.1,8,14 Among adults with SCD, approximately 30% develop chronic renal failure, which contributes to the mortality of the disease.

Management

Long term management of SCD focuses on preventing infection and organ damage. As such, patients with SCD should receive vaccinations against meningococcus, pneumococcus, Hemophilus influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2.14,15

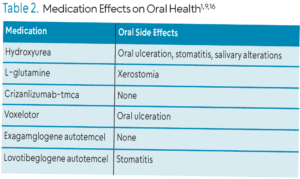

Several therapeutic approaches to manage acute complications of SCD have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration including hydroxyurea, L-glutamine, crizanlizumab-tmca, voxelotor, exagamglogene autotemcel, and lovotibeglogene autotemcel (Table 2). Hydroxyurea is an antimetabolite that increases fetal hemoglobin expression, which may decrease the severity of SCD complications. L-glutamine protects sickled RBCs from hemolysis and oxidative damage and may lower incidence of hospitalization, chest crisis, and VOCs. Crizanlizumab-tmca is a humanized, anti-P-selectin monoclonal antibody administered intravenously to prevent VOCs by impeding RBCs, white blood cells, and platelets from forming aggregates and adhering to blood vessel walls. Voxelotor inhibits HbS polymerization and RBC sickling by modifying hemoglobin’s affinity for oxygen, which may reduce inflammation and improve complications. Exagamglogene autotemcel is an autologous gene therapy and may increase fetal hemoglobin. L ovotibeglogene autotemcel is an anti-sickling gene therapy that may produce a modified hemoglobin that reduces or eliminates the sickling of red blood cells, and may reduce VOCs.9,14,16

Erythrocyte transfusion is used to treat acute and chronic complications of SCD by reducing the occurrence of stroke, ACS, and VOCs. Approximately 90% of adults with SCD will receive at least one transfusion.12 Indications for erythrocyte transfusion include stroke, ACS, acute exacerbation of anemia, and perioperative conditions. Alloimmunization to RBC antigens is a major complication associated with transfusions in patients with SCD. In the US, approximately 0.5% to 1.5% of the general population experiences alloimmunization, compared to 18% to 76% of patients with SCD.12 Iron overload is another serious complication of transfusion and may cause many systemic complications including oxidative stress which can result in the dysfunction of the liver, heart, and endocrine organs.17

Erythrocyte transfusion is used to treat acute and chronic complications of SCD by reducing the occurrence of stroke, ACS, and VOCs. Approximately 90% of adults with SCD will receive at least one transfusion.12 Indications for erythrocyte transfusion include stroke, ACS, acute exacerbation of anemia, and perioperative conditions. Alloimmunization to RBC antigens is a major complication associated with transfusions in patients with SCD. In the US, approximately 0.5% to 1.5% of the general population experiences alloimmunization, compared to 18% to 76% of patients with SCD.12 Iron overload is another serious complication of transfusion and may cause many systemic complications including oxidative stress which can result in the dysfunction of the liver, heart, and endocrine organs.17

Hemopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the only cure for SCD currently available. Treatment success is contingent on donor compatibility, recipient age, and disease severity.1,9,14 Stem cells are sourced from a matched related donor to avoid complications such as graft-vs-host disease. Management of HSCT related complications remains a significant challenge and is an area of ongoing research.

Oral Implications

Several oral manifestations of SCD may affect tooth structure, oral mucosa, periodontal tissues, and bone. The most common are paleness of the oral mucosa (pallor), delayed tooth eruption, enamel and dentin mineralization disorders, papillary atrophy of the tongue, mandibular osteomyelitis, nerve damage, orofacial pain, pulpal necrosis of healthy teeth, and malocclusion in children and teens.8,15,18,19

Pallor of the oral mucosa is the most common oral manifestation.19 The mucosa may appear yellowish due to hemolysis and commonly appears on the soft palate and floor of the mouth. Also common is papillary atrophy of the tongue, which may affect the entire surface, causing it to appear reddish and smooth. Sudden onset of pulpal necrosis or pain in healthy teeth occurs 8.33 times more among patients with SCD patients compared to patients without it due to vascular occlusive events in the pulpal microvasculature.8,15,19-21

Bone manifestations of SCD include bone pain and osteomyelitis of the jaws. Chronic anemia may induce bone marrow hyperplasia, which can impede blood flow, leading to bone ischemia, necrosis, and episodes of bone pain.13,19 Due to decreased immune function, osteomyelitis occurs 200 times more frequently in patients with SCD than the typical population.8 Other triggers of bone pain may include periods of hypoxia, dehydration, general anesthesia, stress, or surgery. Bone pain occurs more frequently in mandibular bone, particularly in posterior regions due to a less developed vascular network in this area. Bone necrosis can be observed radiographically in the mandible, maxilla, and throughout the skeleton, appearing as small radiolucent lesions.19 Osteomyelitis in the posterior mandibular region may be managed with sequestrectomy, curettage, debridement, corticotomy and resection of mandible and affected muscles.15

Vascular infarction of the mental nerve or its branches may lead to loss of sensation in the chin and lower lip, also known as numb chin syndrome (NCS). It can be triggered by VOCs, which cause ischemia, painful crises in mandibular bone, hypoesthesia, paresthesia, or pain in the chin and lower lip. Nerve damage may also affect tooth sensation, resulting in false negative tooth vitality testing. Neuropathy of the mental nerve occurs 2.2 times more in patients with SCA than the general population.19 Currently no treatment exists for NCS, however, management includes resolution of VOCs, and sensation may eventually return after several months.19,20,22

Data are inconclusive regarding the incidence of caries among patients with SCD. This patient population may be at increased risk due to enamel hypomineralization and decreased oral hygiene due to frequent hospitalizations. Certain medications used to treat SCD, including hydroxyurea, may also alter salivary pH and flow, and others contain sucrose.16,18,23 Many patients with SCD frequently use prophylactic antibiotics such as penicillin which may decrease colonization by Streptococcus mutans, impacting caries risk.21

SCD is also a risk factor for moderate to severe dental malocclusion due to resultant changes in the craniofacial bones.8,21,24 Increased demand for erythropoiesis may cause compensatory bone marrow expansion, leading to pathologic changes which can be observed radiographically. The most common craniofacial bone abnormalities in SCD include maxillary protrusion with flaring of maxillary incisors, overjet, overbite, retrusion or thin border of the mandible, increased prominence of zygomatic and parietal bones, large trabecular bone, and frontal bossing.21,24 Among patients with SCD, 30.1% required orthodontic treatment compared to 2.7% of controls.15

Conflicting evidence exists about the link between SCD and periodontitis. Many studies demonstrate no correlation, while others suggest a potential association through shared inflammatory pathways.17,25,26 Inflammation is a core component of the pathophysiology of both periodontitis and SCD, and can precipitate VOC. Iron overload, a complication of blood transfusion used to manage SCD, may also play a role in the development of periodontal diseases. Iron plays a role in periodontal health as a growth factor and regulator of periodontal pathogens. Essential for normal differentiation of human periodontal ligament stem cells, iron in excess may negatively impact alveolar bone remodeling.17

Dental Management

Prevention is the best approach for patients with SCD. Oral health screening should occur every 6 months and include evaluation of pulp, detection of dental infection, periodontal evaluation, and orthodontic evaluation.10,15,26 Pulpal necrosis is common among this population, so routine evaluation of pulp is recommended.

Detecting dental infections and subsequent treatment are critical because they may precipitate a VOC or exacerbate an existing crisis.1 A strict periodontal screening regimen should be implemented to assess oral hygiene and detect periodontal inflammation. The importance of good oral hygiene must be emphasized, especially during periods of hospitalization.10,25,26 Malocclusion may require orthodontic treatment, which needs to incorporate rest periods to minimize pain. Close monitoring of bone response and pulpal health is needed to avoid SCD complications.15

Stress is a well-established trigger for sickle cell crisis, therefore minimizing stress during dental appointments is key. An anxiety assessment at the initial visit is prudent. Profound local anesthesia is suggested to reduce stressful events that may trigger VOC.19 Conscious sedation using an equimolar mixture of oxygen and nitrous oxide (MEOPA) is preferred to general anesthesia due to fewer complications; however, 100% oxygen should be administered for 4 to 5 minutes when the MEOPA is stopped to avoid hypoxia, which may induce VOC.19,24 Patients with mild anxiety may be prescribed anxiolytics or sedatives. Barbiturates and narcotics should be avoided as they may cause respiratory suppression, leading to VOC.24 Patients with severe anxiety or multiple dental or surgical procedures may require intravenous sedation or general anesthesia and should be referred to a hospital with hematology expertise to ensure the patient remains hydrated, warm, and receives oxygen therapy throughout the procedure.15,24

Patients with SCD may experience serious side effects from medications so post-operative pain management must be approached with caution. Acetaminophen or acetaminophen with codeine is most often recommended.15,22 Steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are contraindicated, while nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be used at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest duration, especially for patients with renal, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular risks.19,24

The literature is evolving on the use of aspirin as a treatment option; however, decreased platelet function, increased bleeding, acidosis, and bone marrow suppression are all possible risks.15,24 Patients with SCD are often mistakenly perceived by healthcare professionals as drug seekers, but pain is a significant characteristic of the disease.

Conclusion

SCD is a complex genetic blood disorder that affects multiple organ systems and significantly reduces quality of life and life expectancy. It is associated with several comorbidities and oral manifestations that impact the provision of dental care. Effective management requires preventive strategies and multidisciplinary care. By recognizing oral implications of SCD, oral health professionals can improve both the oral and overall health of affected individuals.

References

- Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 2010;376:2018-2031.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data and Statistics on Sickle Cell Disease. CDC.Available at cdc.gov/sickle-cell/data/index.html. Accessed November 24, 2025.

- GBD 2021 Sickle Cell Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national prevalence and mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000–2021: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10:e585‑e599.

- Archer NM, Petersen N, Clark MA, et al. Resistance to Plasmodium falciparum in sickle cell trait erythrocytes is driven by oxygen-dependent growth inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:7350–7355.

- Esoh K, Wonkam A. Evolutionary history of sickle-cell mutation: implications for global genetic medicine. Hum Mol Genet. 2021;30:R119-R128.

- Ancillotti LHDSF, Abreu MHNG, Marinho AMCL, Santos MPAD. Validating evidence for the knowledge, management and involvement of dentists in a dental approach to sickle-cell disease. Braz Oral Res. 2024;38:e026.

- Sundd P, Gladwin MT, Novelli EM. Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019;14:263-292.

- da Fonseca M, Oueis HS, Casamassimo PS. Sickle cell anemia: a review for the pediatric dentist. Pediatr Dent. 2007;29:159-169.

- Barak M, Hu C, Matthews A, Fortenberry YM. Current and future therapeutics for treating patients with sickle cell disease. Cells. 2024;13:848.

- Manwani D, Frenette PS. Vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease: pathophysiology and novel targeted therapies. Blood. 2013;122:3892-3898.

- Barshtein G, Pajic-Lijakovic I, Gural A. Deformability of Stored Red Blood Cells. Front Physiol. 2021;12:722896.

- Chou ST. Transfusion therapy for sickle cell disease: a balancing act. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:439-446.

- Wang MX, Pepin EW, Verma N, Mohammed TL. Manifestations of sickle cell disease on thoracic imaging. Clin Imaging. 2018;48:1-6.

- Conway O’Brien E, Ali S, Chevassut T. Sickle cell disease: an update. Clin Med (Lond). 2022;22:218-220.

- Mulimani P, Ballas SK, Abas AB, Karanth L. Treatment of dental complications in sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;12:CD011633.

- Brandão CF, Oliveira VMB, Santos ARRM, et al. Association between sickle cell disease and the oral health condition of children and adolescents. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18:169.

- Costa SA, Moreira ARO, Costa CPS, Carvalho Souza SF. Iron overload and periodontal status in patients with sickle cell anaemia: A case series. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47:668-675.

- Fernandes ML, Kawachi I, Corrêa-Faria P, Pattusi MP, Paiva SM, Pordeus IA. Caries prevalence and impact on oral health-related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:68.

- Chekroun M, Chérifi H, Fournier B, et al. Oral manifestations of sickle cell disease. Br Dent J. 2019;226:27-31.

- Schlosser BJ, Pirigyi M, Mirowski GW. Oral manifestations of hematologic and nutritional diseases. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44:183-vii.

- Ralstrom E, da Fonseca MA, Rhodes M, Amini H. The impact of sickle cell disease on oral health-related quality of life. Pediatr Dent. 2014;36:24-28.

- Bedrouni M, Touma L, Sauvé C, et al. Numb chin syndrome in sickle cell disease: a systematic review and recommendations for investigation and management. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:2933.

- Yue H, Xu X, Liu Q, et al. Association between sickle cell disease and dental caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hematology. 2020;25:309-319.

- Kawar N, Alrayyes S, Yang B, Aljewari H. Oral health management considerations for patients with sickle cell disease. Dis Mon. 2018;64:296-301.

- de Carvalho HL, Thomaz EB, Alves CM, Souza SF. Are sickle cell anaemia and sickle cell trait predictive factors for periodontal disease? A cohort study. J Periodontal Res. 2016;51:622-629.

- Sari A, Ilhan G, Akcali A. Association between periodontal inflamed surface area and serum acute phase biomarkers in patients with sickle cell anemia. Arch Oral Biol. 2022;143:105543..

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January/February 2026; 24(1):28-31