How AI-Powered Ergonomics May Help Save Dental Careers

Computer vision is emerging as dentistry’s newest tool to combat musculoskeletal disorders by delivering fast, objective posture assessments and actionable feedback.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is taking dentistry by storm, impacting many aspects of the profession including diagnostics, treatment planning, and business operations.1 One subset of AI, computer vision, is emerging as an innovative approach to improve ergonomics. Adding to dentistry’s AI arsenal, this image-processing technology can support oral health professionals in reducing musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) in the workplace.

Oral health professionals are at increased risk for MSDs due to the need for static and awkward postures, repetitive motions, and vibrating equipment.2 With MSDs affecting an estimated 78% of oral health professionals, effective interventions are critical.2 Through computer vision use in ergonomic assessments, dentistry can leverage this technology to respond to its MSD challenge.

Ergonomic Assessments

To fully understand AI’s impact on ergonomics, the foundations of an ergonomic assessment must be reviewed. Ergonomic assessments involve observing and analyzing the subject’s body mechanics; they are performed to address risk factors for MSDs. Ergonomic professionals facilitate these assessments, which can be conducted on working individuals or for research purposes.3,4

The most widely used ergonomic assessment tools are the rapid upper limb assessment (RULA) and rapid entire body assessment (REBA).3 RULA quickly measures risk by analyzing body posture, force, and repetition concentrating on the neck, trunk, and upper extremities. Scores range from one to seven, with one designating acceptable posture. A score of seven indicates immediate investigation of posture and that changes are needed. REBA looks at the whole body and is commonly used in manual work, healthcare, and service industries. REBA scores range from one to 15, with one being low risk and 15 being very high risk.3,4

Ergonomic assessment tools, such as RULA and REBA, allow for a measured evaluation of body alignment and are often used within the dental profession.5 A recent pilot study by Partido et al6 used RULA to examine the impact of an alternating seating-standing protocol on posture for dental hygiene students. While not statistically significant, results showed that the RULA scores of the students alternating seating and standing during scaling were lower than the control group that remained seated.

Traditionally, ergonomic evaluations are done through human observation, but this method is prone to user error and bias and is time consuming.7 An alternative is to have the subject use wearable devices to measure posture. While accurate, this technique can be cumbersome and it limits the natural movement of the subject.8 Incorporating computer vision into assessments may reduce the limitations that traditional methods face.

Computer Vision Artificial Intelligence

Ergonomic AI technology uses computer vision, which processes and analyses visual content such as images or videos. By translating an image into numbers, the computer can process the data into useful applications. With vast applicability, its uses vary from simple to complex, including facial and object recognition, self-driving cars, and sports performance analysis.

Within the ergonomics field, computer vision identifies an individual’s posture (joint angles), speed, and force used. From the data collected, AI can quickly calculate ergonomic scores such as REBA and RULA. Other applications include a comparison of before and after ergonomic interventions, calculations of large data sets, and prediction of subjects’ future movements.

Computer vision for ergonomics has been validated for accuracy and comes with many benefits.7 A systematic review of computer vision use in ergonomics found that it costs less than wearable device methods, is noninvasive, holds the potential for automatic features, and can be used in a variety of environments.7

One of the main challenges noted in the review was obstacle occlusion, or a physical object blocking part of the subject’s body. Another limitation was the limited amount of real-world application research conducted thus far, potentially affecting accuracy and data-set benchmarks. However, computer vision technology is gaining in popularity. As is the nature of AI, the more data available to the technology, the more it can learn, improving precision and application.7

Ergonomic computer vision has been employed in various professions such as construction, healthcare, administration, agriculture, and transportation.7 In a recent narrative review of computer vision use among cardiothoracic surgeons, the benefits included the ability to provide feedback on the surgeon’s technique and the potential to investigate the link between aspects of procedures and patient outcomes.9 It was also noted that computer vision allows for movement tracking in the operating room without the use of special equipment or markers.9

Use of Ergonomic Artificial Intelligence

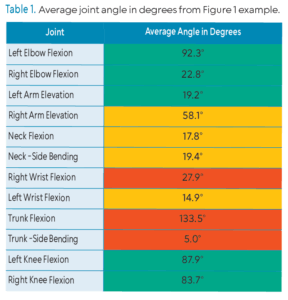

With many other professions now using AI for ergonomics, dentistry should consider doing the same. The following examples show applications within the dental field by using an ergonomic AI program facilitated by an ergonomic specialist. In Figure 1, a color-coded skeleton overlay of the clinician illustrates the risk for MSDs. Green indicates low risk with joint angles within normal range. Yellow demonstrates moderate risk and red indicates high risk.

Figure 1 shows a screenshot of a video recording taken of a dental hygienist hand scaling in the 9 o’clock position. Using computer vision, data, such as joint angles, joint speed, and time spent in each respective risk category ,were quickly obtained. Table 1 shows the average postural angle of each joint attained during the duration of the video (15 seconds) and the respective risk denoted by color. For example, the clinician’s right wrist flexion measured 27.9° and is categorized within the red, high-risk range. Within the ergonomic AI program, REBA and RULA scores can also be generated. For this example, the REBA score was 10, indicating high risk, requiring immediate intervention.

Figure 1 shows a screenshot of a video recording taken of a dental hygienist hand scaling in the 9 o’clock position. Using computer vision, data, such as joint angles, joint speed, and time spent in each respective risk category ,were quickly obtained. Table 1 shows the average postural angle of each joint attained during the duration of the video (15 seconds) and the respective risk denoted by color. For example, the clinician’s right wrist flexion measured 27.9° and is categorized within the red, high-risk range. Within the ergonomic AI program, REBA and RULA scores can also be generated. For this example, the REBA score was 10, indicating high risk, requiring immediate intervention.

Based on the data collected, ergonomic interventions can then be recommended by an ergonomic specialist. Potential solutions to decrease risk and improve ergonomics include but are not limited to modifications in patient-operator positioning to achieve neutral posture and a saddle stool to improve forward flexion of the trunk.

Based on the data collected, ergonomic interventions can then be recommended by an ergonomic specialist. Potential solutions to decrease risk and improve ergonomics include but are not limited to modifications in patient-operator positioning to achieve neutral posture and a saddle stool to improve forward flexion of the trunk.

Not only are the data from the assessments insightful, but the visual feedback for oral health professionals can also be impactful.10-12 With the addition of video and the skeleton overlay showing risk, clinicians can receive constructive feedback to improve their ergonomics. As demonstrated by a recent study conducted with surgeons utilizing a computer vision ergonomic AI app, residents were able to reduce their percentage of time spent in an unsafe neck joint angle by 61%.13 Adopting similar ergonomic AI approaches in dentistry could provide comparable outcomes. While more research is needed, the potential for improved neutral posture for oral health professionals is compelling.

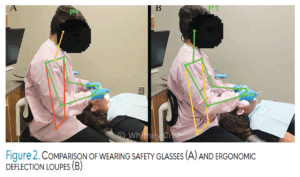

Another benefit of ergonomic AI technology is the ability to quickly compare ergonomic interventions. Figure 2 shows a dental hygiene student wearing standard safety glasses (A) in contrast to ergonomic deflection loupes (B). The safety glasses resulted in an average neck flexion of 25.8°, while deflection loupes reduced neck flexion to an average of 7°.

When using computer vision AI with video recording, clinicians must protect patient and provider privacy, comply with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, and ensure all recordings are handled securely.

When using computer vision AI with video recording, clinicians must protect patient and provider privacy, comply with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, and ensure all recordings are handled securely.

Conclusion

AI use in ergonomics is rising, allowing for quantitative and objective evaluations that support data-driven solutions. The dental profession can take advantage of this emerging technology to address its struggle with ergonomics and MSDs. Whether it’s to help individual clinicians, students, or for future research, AI technology will bring exciting developments to ergonomics in dentistry.

References

- Xie B, Xu D, Zou XQ, Lu MJ, Peng XL, Wen XJ. Artificial intelligence in dentistry: A bibliometric analysis from 2000 to 2023. J Dent Sci. 2024;19:1722-1733.

- Lietz J, Kozak A, Nienhaus A. Prevalence and occupational risk factors of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals in Western countries: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2018;13:e0208628.

- Joshi M, Deshpande V. A systematic review of comparative studies on ergonomic assessment techniques. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2019;74:102865.

- Kee D. Systematic comparison of OWAS, RULA, and REBA based on a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:595.

- Danylak S, Walsh L, Zafar S. Measuring ergonomic interventions and prevention programs for reducing musculoskeletal injury risk in the dental workforce: a systematic review. J Dent Educ. 2024;88:128-141.

- Partido B, Henderson R, Lally M. Impact of a seated-standing protocol on postures and pain among undergraduate dental hygiene students: a pilot study. J Dent Hyg. 2021;95:70-78.

- Egeonu D, Jia B. A systematic literature review of computer vision-based biomechanical models for physical workload estimation. Ergonomics. 2025l68:139-162.

- Sabino I, Maria, Cepeda C, et al. Application of wearable technology for the ergonomic risk assessment of healthcare professionals: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2024;100:103570-103570.

- Constable MD, Hubert, Clark S. Enhancing surgical performance in cardiothoracic surgery with innovations from computer vision and artificial intelligence: a narrative review. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2024;94:19.

- Mills M, Smilyanski I, Giblin‐Scanlon L, Vineyard J. What are the effects of photographic self‐assessment on students’ risk for musculoskeletal disorders using rapid upper limb assessment. J Dent Educ. 2020;84:749-754.

- Partido B, Henderson R, Kennedy M. Improving the awareness of musculoskeletal disorder risks among dental educators. J Dent Educ. 2019;83:e1-e8.

- Partido B, Henderson R. Reducing the risks for musculoskeletal disorders utilizing self-assessment and photography among dentists and dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2021;95:36-41.

- Barbara C.S. Hamilton, Dairywala MI, Highet A, et al. Artificial intelligence based real-time video ergonomic assessment and training improves resident ergonomics. Am J Surg. 2023;226:741-746.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January/February 2026; 24(1):18-20