Dry Mouth May Be First Sign of Diabetes

Dental hygienists are well-positioned to note the early signs and symptoms of diabetes, including dry mouth.

A prevalent chronic disease, diabetes presents a pervasive healthcare challenge both within the United States and globally. According to the most recent estimates from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2021 roughly 38.4 million individuals in the US across all ages had diabetes, reflecting 11.6% of the population. Among adults age 18 and older, 38.1 million (or 14.7%) had diabetes.1 The prevalence of diabetes jumps to 29.2% in adults ages 65 and older.1 While diabetes seems ubiquitous, this does not diminish its serious health implications.

Diabetes mellitus is a heterogeneous collection of disorders characterized by dysfunction in blood glucose regulation. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes are the primary subclassifications but have different pathophysiological presentations.2 Type 1 diabetes accounts for 5% to 10% of cases and is characterized by the inability of the body to produce the hormone insulin due to autoimmune destruction of the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas. Blood glucose increases but cannot be delivered to cells.2

In contrast, individuals with type 2 diabetes may produce insulin, but they experience insulin resistance, meaning that their cells cannot effectively use insulin. Type 2 diabetes can develop through a complex interplay of genetics, environment, and behavioral factors. While type 2 diabetes does not discriminate by age, type 1 tends to have a younger age of onset with a lower body mass index and unintended weight loss.3 Overweight, obesity, and especially waist circumference are significant risk factors for type 2 diabetes.4

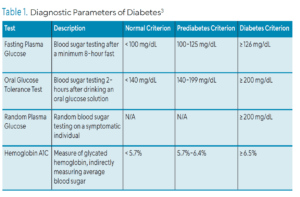

Diagnosis of diabetes is made based on either fasting plasma glucose, oral glucose tolerance test, or HbA1c. Prediabetes occurs when these parameters are elevated but not yet at the diagnostic threshold of type 2 diabetes. Table 1 outlines the diagnostic parameters of diabetes.3 Other less common etiologies of diabetes also occur, such as gestational diabetes and damage from pancreatitis and cystic fibrosis. Regardless of etiology and influencing factors (genetics and environment), hyperglycemia (high blood glucose) is the clinical hallmark of these diabetes diseases.3

Complications of Diabetes

Chronic hyperglycemia from diabetes can lead to a number of complications including microvasculature damage, atherosclerosis, nephropathy, retinopathy, increased vascular permeability, and vascular cell apoptosis.5 These changes may progress and manifest as visual loss, problems with foot circulation and nerve response, stroke, and predisposition to infections.6

Oral complications are of particular concern to oral health professionals. Chronic high blood sugar from diabetes can adversely impact the oral microbiome, impair immunological responses, elevate inflammatory factors, increase advanced glycation end products, alter fibroblast function, and induce oxidative stress.4,7 Hyperglycemia also elevates subgingival glucose levels, promoting dysbiosis. Secondary to impaired immune function, healing can be compromised and host susceptibility amplified.4 Periodontal diseases in patients with poorly controlled diabetes can be more severe and more difficult to control.8

Dry Mouth

While periodontitis is an important focal point in the understanding of diabetes and oral health, dry mouth is another critical oral change that requires attention. Polyuria, dehydration, microcirculatory alterations in salivary glands, and autonomic neuropathy are believed to contribute to dry mouth in diabetes.9–12 Although the terms hyposalivation and xerostomia are often used synonymously, they in fact have two different meanings. Xerostomia is the patient’s subjective perception of dry mouth and may or may not be accompanied by clinical observation of hyposalivation. Xerostomia is often a manifestation of salivary gland hypofunction but can occur with or without a decrease in saliva production. Hyposalivation is a clinically observed decrease in saliva production resulting in varying degrees of dry mouth. A systematic review by López-Pintor et al,11 compared the presence of xerostomia in patients with and without diabetes found a higher prevalence of xerostomia in the diabetic groups at rates of 12.5% to 53.5% compared to rates of 0 to 30% in the nondiabetic control groups.

This is consistent with a study by Shahbaz et al,13 who found that participants meeting the diabetes and prediabetes diagnostic criteria, who were not previously diagnosed before the study, were statistically more likely to report a history of dry mouth and present clinically with thick, ropy saliva.

Varied measurement criteria across studies can challenge comparison, but despite these differences, reviews suggest higher rates of hyposalivation in patients with diabetes as well as reported dry mouth.11,14,15 Salivary dysfunction is most pronounced in individuals with the poorest glycemic control.12,14,15

Other systemic conditions, such as Sjögren syndrome and head and neck radiation, are associated with dry mouth. In addition, an estimated 400-plus medications may impair salivary function, including antidepressants, sedatives, antihistamines, and antihypertensives.16 For example, considering that hypertension and its pharmacological management are common, and the fact that diabetes and hypertension are frequently comorbid, there may be compounding factors in the dry mouth experience of patients with diabetes.17,18 These and other potential causes of dry mouth may mask or distort the clinician’s perception of dry mouth’s underlying cause in patients with diabetes and comorbidities.

Saliva helps cleanse the oral cavity, lubricates and protects the oral mucosa, facilitates swallowing, maintains oral pH, encourages remineralization, and supports host response through antimicrobial properties.16 Consequences of reduced salivary flow can include increased glucose concentrations, diminished antimicrobial action, and an increased risk for and severity of periodontal diseases.19 Further, patients with dry mouth may have erythematous mucosa, cracked lips, loss of tongue papilla, and an increase in irritation and traumatic lesions due to friction from poor lubrication. They may need to drink more while eating and may need to sip water at night to alleviate their dry mouth. Root surface caries; Candidiasis; oral malodor; trouble swallowing, chewing, and eating; and irritation from dentures are all possible sequelae.10,16

Identifying Dry Mouth

Identifying dry mouth is an important first step in its management. In addition to patient reports of dry mouth, positive responses to any of these questions have been associated with reduced saliva:16

- Does the amount of saliva in your mouth seem to be too little?

- Does your mouth feel dry when eating a meal?

- Do you sip liquids to aid in swallowing dry food?

Other questionnaires, such as the Summated Xerostomia Inventory-Dutch Version, have been validated for use in clinical and epidemiological settings.10,20 Clinical assessment of hyposalivation involves examining for signs such as dry mucosa, smooth gingiva, palatal debris, mouth mirror sticking to buccal mucosa, and minimal salivary pooling in the floor of the mouth. Salivary flow can be objectively measured via sialometric testing.11 Other investigatory measures, such as imaging and minor duct biopsy, can also be considered.10

Undiagnosed Diabetes

Of the 37.1 million adults with diabetes in the US, 23% (or 8.5 million adults) were undiagnosed (based on meeting laboratory criteria). That amounts to roughly 3.4% of all US adults having undiagnosed diabetes.1 Oral health professionals are well-versed in the link between diabetes control and periodontal diseases as well as in dry mouth management. However, given the prevalence of dry mouth, diabetes, and, more specifically, undiagnosed diabetes, dry mouth must be considered as a possible symptom of undiagnosed diabetes in xerostomia-reporting patients. During the time between the onset of diabetes and diagnosis, subclinical and unattributed systemic damage could occur.21

The increasing incidence of diabetes, including undiagnosed diabetes, raises the stakes for screening, education, and management, and the dental setting is a fitting location for screening via risk assessment.22 While dental settings are likely not equipped for biochemical assay (such as HbA1c), the CDC and the American Diabetes Association have collaborated on a simple prediabetes risk screening tool that can be completed online quickly or easily printed.8,22–24 It is available here: cdc.gov/prediabetes/risktest/index.html. Patients should be referred to follow up with their physician on their screening findings for timely evaluation and definitive diagnostic measures.

Conclusions

Statistically, oral health professionals should approach patient care assuming they will encounter patients with undiagnosed diabetes. The common report of dry mouth among patients should not just be managed, but investigated, warranting thorough medical history review, clinical assessment, screening measures to best understand a patient’s diabetes risk, and referrals as needed for further medical evaluation. Early intervention and timely diagnosis can save the patient physical, financial, and emotional hardship, and may improve systemic and oral health outcomes and quality of life.

References

1. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report. Available at cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html. Accessed August 8 2025.

2. Sapra A, Bhandari P. Diabetes. Available at statpearls.com/point-of-care/20429. August 8 2025.

3. El Sayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes – 2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(Supplement_1):S19-S40.

4. Kocher T, König J, Borgnakke, WS, Pink C, Meisel P. Periodontal complications of hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus: epidemiologic complexity and clinical challenge. Periodontol 2000. 2018;78:59-97.

5. Rask-Madsen C, King GL. Vascular complications of diabetes: mechanisms of injury and protective factors. Cell Metabolism. 2013;17(1):20-33.

6. National Institutes of Health. Diabetes Complications. Available at medlineplus.gov/diabetescomplications.html. August 8, 2025.

7. Polak D, Shapira L. An update on the evidence for pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontitis and diabetes. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:150-166.

8. Sanz M, Ceriello A, Buysschaert M, et al. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: Consensus report and guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes by the International diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;137:231-241.

9. Mortazavi H, Baharvand M, Movahhedian A, Mohammadi M, Khodadoustan A. Xerostomia due to systemic disease: a review of 20 conditions and mechanisms. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4: 503-510.

10. Millsop JW, Wang EA, Fazel N. Etiology, evaluation, and management of xerostomia. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35 468-476.

11. López-Pintor RM, Casañas E, González-Serrano J, et al. Xerostomia, hyposalivation, and salivary flow in diabetes patients. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:4372852.

12. Rohani B. Oral manifestations in patients with diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2019;10:485-489.

13. Shahbaz M, Kazmi F, Majeed HA, Manzar S, Qureshi FA, Rashid S. Oral manifestations: a reliable indicator for undiagnosed diabetes mellitus patients. Eur J Dent. 2023;17:784-789.

14. Rahiotis C, Petraki V, Mitrou P. Changes in saliva characteristics and carious status related to metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Dent. 2021;108:103629.

15. Chávez EM, Borrell LN, Taylor GW, Ship JA. A longitudinal analysis of salivary flow in control subjects and older adults with type 2 diabetes. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Pathol, Oral Radiol. 2001;91:166-173.

16. Plemons JM, Al-Hashimi I, Marek CL. Managing xerostomia and salivary gland hypofunction. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:867-873.

17. Samanic CM, Barbour KE, Liu Y, et al. Prevalence of self-reported hypertension and antihypertensive medication among adults – United States 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:393-398.

18. Petrie JR, Guzik TJ, Touyz RM. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: clinical insights and vascular mechanisms. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:575-584.

19. Negrato CA, Tarzia O. Buccal alterations in diabetes mellitus. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2010;2:3.

20. Thompson WM, van der Putten GJ, de Baat C, et al. Shortening the xerostomia inventory. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Pathol, Oral Radiol and Endo. 2011;112:322-327.

21. Teeuw WJ, Kosho MXF, Poland DCW, et al. Periodontitis as a possible early sign of diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5:e000326.

22. Mariño R, Priede A, King M, Adams GG, Sicari M, Morgan M. Oral health professionals screening for undiagnosed type 2 diabetes and prediabetes: the iDENTify study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22:183.

23. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes and Oral Health. Available at diabetes.org/diabetes/keeping-your-mouth-healthy. Accessed August 8, 2025.

24. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prediabetes Risk Test. Available at: cdc.gov/prediabetes/takethetest. Accessed August 8, 2025.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September/October 2025; 23(5):12-15.