Break the Cycle of Early Childhood Caries

With tooth decay affecting millions of children worldwide, coordinated prevention, risk assessment, and family-centered care are the keys to effective management.

Dental caries remains the most common, chronic, preventable disease impacting children globally.1 A multifactorial condition, early childhood caries (ECC) is characterized by the presence of one or more decayed, missing or filled (DMF) teeth in the primary dentition of children younger than age 6.1,2

Any smooth surface cavitated lesion is considered severe early childhood caries (S-ECC) among children younger than age 3.2 In 2019, an estimated 43% (514 million) of children ages 1 to 9, across the globe, had dental caries in primary teeth.3 In the United States, between 2017 and 2020, nearly half (46%) of children ages 2 to 19 had untreated or restored dental caries. Among children ages 2 to 5, 22% had untreated or restored dental caries, and this prevalence increased with age.4 Moreover, children from households with a federal poverty level (FPL) less than 350% had a higher prevalence of untreated or restored dental caries than those living above 350% of the FPL.4

ECC can impact a child’s oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL), which is the impact of oral disease on an individual’s physical functioning and psychological and social well-being.5-7 A recent systematic review demonstrated that higher DMF scores were related to greater impact on a child’s OHRQoL and increased visits to the emergency department for dental problems.7

When compared to children without ECC, children with ECC exhibit a significantly greater likelihood of developing caries in their permanent dentition and are more susceptible to adverse health and social outcomes, including school absenteeism, sleep disturbances, anemia and infections, impaired physical growth and development, reduced quality of life, and social isolation.8-11

Determining a Successful Approach to Early Childhood Caries Prevention

The multifactorial risks associated with ECC must be considered prior to birth. The biological mechanisms of oral health, including the microflora, host and teeth, and diet, are connected to modifiable risk factors that encompass family-level, community-level, and child-level influences. This complex system influences children’s oral health outcomes, specifically, ECC.1,12

Conversations related to oral health behaviors and practices should begin during the gestational period. This period is an ideal time to provide dental care and education regarding dental caries prevention for the expectant mother to protect both her oral health and that of the child.13 Communication strategies, such as motivational interviewing (MI), are effective in reducing dental caries among children.14-16 Furthermore, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) promotes collaborative efforts for preventive practices among healthcare professionals and caregivers as a strategy to decrease ECC among children, which minimizes the burden on the child, family, and society.8

The Impact of Dietary Behaviors on Early Childhood Caries

Dietary behaviors are at the core of ECC and occur prior to the birth of the child through familial behaviors.1 The mother, caregivers, and family establish dietary habits for the child. Therefore, providing dietary counseling to caregivers is essential to promote healthier behaviors in children and serves as a key preventive measure against ECC.8

Aligning the nutrition of foods, the timing of intake, and the frequency of consumption is also a large part of nutritional guidelines for children with ECC. Nutritional recommendations to caregivers should include advising against cariogenic foods/sugary drinks near bedtime, assessing the consumption of sugar in food and drinks, evaluating sticky foods and children’s gummy multivitamins, and educating caregivers on the importance of avoiding foods that can remain in the pits and fissures of primary molars.17 The caregiver may want to track the frequency of cariogenic foods and beverages, as these cause an acidic pH in the mouth, further contributing to ECC.

The Influence of Oral Health Behaviors on Early Childhood Caries

Prevention of dental caries in children is cost effective and relates to decreased treatment needs. Early establishment of a dental home by age 1 is a sustained national recommendation by the AAPD.18,19 Moreover, establishing a collaborative relationship between dentists and physicians at the community level can support primary care providers recommending a dental visit for children by age 1, based on risk assessment.20

Guidelines for ECC prevention include community water fluoridation, specifically for vulnerable communities, and a minimum of 1,000 to 1,500 ppm fluoride toothpaste used twice daily for all children.1,8 A smear of toothpaste should be used for children younger than age 3 and a pea-sized amount for children ages 3 to 6.6,21

Effective at-home oral hygiene is essential, especially for children in dental care shortage areas who face transportation barriers to in-office care. Recent data from a cross-sectional study of the geographic distribution of accessibility to US dental clinics indicated that 24.7 million people live in a dental care shortage area, which is defined as less than one dental office per 5,000 residents.22

Strategies for Effective Management of Early Childhood Caries

The management of ECC should be based on caries risk assessment, parent/caregiver participation in oral self-care, age and current oral health status.5 In 2020, a scoping review critically evaluated global guidelines, policies, and guidance for the treatment of ECC.5 Inclusion criteria were studies from 2011-2018 written in English and ranged from the US, United Kingdom, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry, and the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. Fifty-two studies were assessed, with 22 meeting criteria for inclusion in the scoping review.

The management of ECC should be based on caries risk assessment, parent/caregiver participation in oral self-care, age and current oral health status.5 In 2020, a scoping review critically evaluated global guidelines, policies, and guidance for the treatment of ECC.5 Inclusion criteria were studies from 2011-2018 written in English and ranged from the US, United Kingdom, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry, and the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. Fifty-two studies were assessed, with 22 meeting criteria for inclusion in the scoping review.

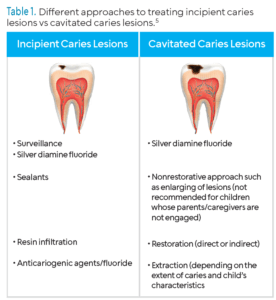

Interestingly, the studies reviewed indicated that the approach for incipient lesions differed from the approach for cavitated carious lesions (Table 1). For incipient caries, a watch approach was indicated, and the application of fluoride varnish (5% professional NaF) or brushing with a nonprescription fluoride toothpaste at home was recommended. This approach is appropriate only when the child has strong parent/caregiver support. Additionally, sealants on occlusal surfaces or composite resin on interproximal surfaces were recommended.

The authors found minimally invasive 38% silver diamine fluoride (SDF) recommended for both cavitated and noncavitated carious lesions.5 A systematic review within the scoping review further concluded and supported SDF’s ability to arrest cavitated and noncavitated lesions.23 The World Health Organization also supports this recommendation.1

Role of the Dental Hygienist in the Prevention and Management of Early Childhood Caries

Oral health professionals must be knowledgeable of the risk, prevention, and management strategies for ECC. Integrating caries risk assessment tools, such as the Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA), will help clinicians assess a patient’s biological and environmental risk factors, such as familial decay history and protective factors, among children ages 0 to 6.24

Dental hygienists, in partnership with healthcare professionals, are instrumental in providing oral hygiene education to caregivers to decrease the risk of ECC. Regular preventive care should be emphasized and related to overall health.25

Dental hygienists, in partnership with healthcare professionals, are instrumental in providing oral hygiene education to caregivers to decrease the risk of ECC. Regular preventive care should be emphasized and related to overall health.25

Motivational interviewing (MI) should be used to promote positive oral health behavior change in patients that can be modeled to their young children. Brief MI, an alternative approach to MI with shorter 5- to 15-minute sessions, works best with the time constraints of dental hygiene appointments.26 While a single session of brief MI may be insufficient to produce behavior change, successive sessions can build on and facilitate long-term improvements in oral health outcomes.

Finally, supporting professional autonomy, expanded scope of practice, and consistent national standards for dental hygienists may help reduce barriers such as limited access to dental care and transportation challenges. Expanding direct access to dental hygienists across the country may promote improved oral and overall health, while reducing dental emergencies.25

Conclusion

ECC is a preventable oral disease experienced by young children. Prevention strategies, such as caries risk assessment, dietary counseling, motivational interviewing, and anticipatory guidance, should be considered for pregnant women and caregivers of young children. Oral health professionals can keep up to date on ECC by reviewing evidence-based literature and attending continuing education courses on best practice for prevention and management.

References

- World Health Organization. Ending childhood dental caries: WHO implementation manual. Available at who.int/publications/i/item/ending-childhood-dental-caries-who-implementation-manual. Accessed December 11, 2025.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Definition of Early Childhood Caries (ECC). Available at aapd.org/assets/1/7/d_ecc.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2025.

- World Health Organization. Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030. Available at who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484. Accessed December 11, 2025.

- Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll MD, et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 prepandemic data files—Development of files and prevalence estimates for selected health outcomes. Natl Health Stat Report. 2021;14:10.15620.

- Corrêa-Faria P, Viana KA, Raggio DP, Hosey MT, Costa LR. Recommended procedures for the management of early childhood caries lesions—a scoping review by the Children Experiencing Dental Anxiety: Collaboration on Research and Education. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:75:1-11.

- Tinanoff N, Baez RJ, Diaz Guillory C, et al. Early childhood caries epidemiology, aetiology, risk assessment , societal burden, management, education and policy: global perspective. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019;29:238-248.

- Zaror C, Matamala-Santander AM, Ferrer M, et al. Impact of early childhood caries on oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2022;20:120-135.

- Policy on Early Childhood Caries: Classifications, Consequences and Preventive Strategies. The Reference Manual Of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2020:79–81.

- Bagis EE, Derelioglu SS, Sengül F, et al. The effect of the treatment of severe early childhood caries on growth-development and quality of life. Children (Basel, Switzerland). 2023;10:411.

- McGrath C, Broder H, Wilson-Genderson M. Assessing the impact of oral health on the life quality of children: implications for research and practice. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:81-85.

- Rodrigues do Amaral M, Freire-Maia J, Bittencourt JM, et al. Early childhood caries and its consequences impact sleep in preschool children. J Dent Child (Chic). 2024;91:25-30.

- Fisher-Owens SA, Gansky SA, Platt LJ, et al. Influences on children’s oral health: A conceptual model. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e510-520.

- National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center. Oral Health Care During Pregnancy Consensus Statement. Available at: mchoralhealth.org/PDFs/OralHealthPregnancyConsensus.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2025.

- Colvara BC, Faustino-Silva DD, Meyer E, Hugo FN, Celeste RK, Hilgert JB. Motivational interviewing for preventing early childhood caries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2021;49:10-16.

- Jahanshahi R, Amanzadeh S, Mirzaei F, Moghadam SB. Does motivational interviewing prevent early childhood caries? a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent (Shiraz). 2022;23:Suppl:161–168.

- Manek S, Jawdekar AM, Katre AM. The effect of motivational interviewing on reduction of new carious lesions in children with early childhood caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2023;16:112–123.

- Ma S, Ma Z, Wang X, et al. Relationship of dietary nutrients with early childhood caries and caries activity among aged 3-5 years- a cross sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2024:24:506.

- Chen J, Meyerhoefer, CD, Timmons E. The effects of dental hygienist autonomy on dental care utilization. Health Econ. 2024;33:1726-1747.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on the Dental Home.Available at https://www.aapd.org/media/policies_guidelines/p_dentalhome.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2025.

- Krol DM, Whelan K, Section On Oral Health. Maintaining and improving the oral health of young children. Pediatrics. 2023:151):1.

- Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Ismail AI, Maertens MP, Rozier RG, Selwitz RH. Diagnosing and reporting early childhood caries for research purposes. J Public Health Dent. 1999; 59:192-197.

- Rahman MS, Blossom JC, Kawachi I, Tipirneni R, Elani HW. Dental clinic deserts in the US: spatial accessibility analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2451625.

- Schmoeckel J, Gorseta K, Splieth CH, Juric H. How to intervene in the caries process: early childhood cares—a systematic review. Caries Res. 2020;54:102-112.

- Featherstone JD, Crystal YO, Alston P, et al. A comparison of four caries risk assessment methods. Front Oral Health. 2021;2: 657518.

- Hammond S. Missed Potential: How Expanding Dental Hygienists’ Roles can Bridge America’s Oral Health Gaps. Available at adha.org/advocacy/adha-white-papers. Accessed December 11, 2025.

- Koerber A. Brief interventions in promoting health behavior change. In: Ramseier CA, Suvan JE. Health Behavior Change in the Dental Practice. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2011:93-112.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January/February 2026; 24(1):22-26