ROBERT DALY/OJOIMAGES/GETTYIMAGESPLUS

ROBERT DALY/OJOIMAGES/GETTYIMAGESPLUS

Expanding Dental Hygiene to the Doctoral Level

Doctoral-level education is necessary to prepare dental hygienists to be health care providers who will challenge prevailing thinking, test theories, lead interprofessional teams, and develop policies to improve oral health.

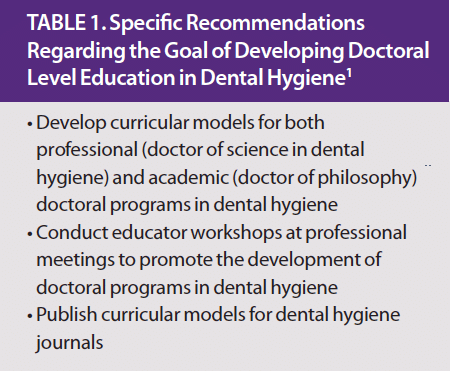

In 2005, the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) published Dental Hygiene: Focus on Advancing the Profession, a document that examined the future of dental hygiene.1 It set goals for dental hygiene education; one of which was to create a doctoral degree program in dental hygiene within 20 years. Table 1 (page 32) lists the specific recommendations related to this goal. It is now 2017, and time to examine what progress has been made in the establishment of doctoral education in dental hygiene.

WHY DOCTORAL EDUCATION?

Doctoral education has evolved in several health care disciplines. Physical therapy, occupational therapy, and physician assistants raised the degree for entry level to a doctoral degree in an effort to ensure the safe and effective provision of care and to improve access to care.2 Pharmacy changed its entry point to doctoral education, while nursing and audiology developed doctoral education programs to better prepare their students for research, education, and practice.3–5 Lagging behind these disciplines has been dental hygiene, which has yet to advance its entry level program from an associate degree to a baccalaureate degree. Nevertheless, there has been strong interest in doctoral education for dental hygiene.

Workshops have been conducted at national meetings and articles have been published supporting the concept of doctoral dental hygiene programs.6–8 The international community of dental hygienists recognized advanced education as desirable at a 2010 workshop.9 Dental hygiene educators have long pursued doctoral degrees outside of their discipline to remain competitive in academic settings, as the terminal degree in dental hygiene remains at the master’s level.

Discussions about doctoral dental hygiene education have addressed the importance of creating dental hygiene scholars and researchers who will expand the body of knowledge for the profession, and who will lead the development of theory unique to the discipline of dental hygiene.10 Tumath and Walsh11 proposed that doctoral education would lead to a higher level of research and grant writing skills, while Ortega and Walsh12 noted that doctorally prepared dental hygienists would teach graduate level dental hygienists to enter administrative roles in health care.

The need for doctoral education is compelling. Tumath and Walsh11 established that graduate dental hygiene students perceive doctoral dental hygiene education as necessary and important. In their survey of 159 graduate learners, 43% expressed interest in enrolling in a doctoral program in the next 1 year to 5 years; more respondents were interested in enrolling in a doctor of dental hygiene practice degree (62%) than a doctor of philosophy program (38%). Reasons noted for pursuing a doctoral degree were to become a better educator, expand clinical practice opportunities, improve research skills, and increase earning potential.10

Recently, Davis et al13 studied dental hygiene educators to assess their perceptions of establishing doctoral education programs in dental hygiene. The primary need for doctoral education included relating equitably with doctoral graduates of other health-related disciplines and expanding the body of knowledge in the dental hygiene discipline. There was strong support for both the doctor of dental hygiene practice and the doctor of philosophy program among study participants.

CURRICULAR OPTIONS

When the ADHA proposed transforming dental hygiene education,14 some programs began by modifying one or several courses in their entry-level curriculum. The faculty of Idaho State University’s Department of Dental Hygiene viewed this transformation as an opportunity to develop curriculum for the doctorate of philosophy in dental hygiene.15 The purpose of this degree is to prepare academicians and researchers to contribute to the scientific body of knowledge for the discipline of dental hygiene. Courses in this program include scholarly identity development, change strategies, theoretical analysis of dental hygiene science, advanced research design, United States and global health systems, global health advocacy, scientific writing and grantsmanship, applied scholarship, electives, and dissertation courses.15

In addition, we created an entry-level doctoral degree in dental hygiene curriculum.15 This innovative program was designed so students would enter the doctoral program with a baccalaureate degree and complete a 4-year curriculum, preparing them to function in all roles of the dental hygienist. Students would be educated as health care providers, not solely as clinicians, and would be prepared to function in a variety of health-care settings. They would be capable of working independently without supervision requirements and working collaboratively in interprofessional environments. Courses would span learning theories, business management, research methods, public health systems, biostatistics, epidemiology, behavioral change, translational research, leadership and organizational change, interprofessional education, dental hygiene diagnostic methods and evaluation, preventive strategies, clinical care, evidence-based dental hygiene practice, health policy and governmental affairs, health informatics, and proposal development and grant management. Students would complete practicum experiences in all major roles of the dental hygienist so they would have first-hand experience in each area prior to graduation.15

Within this past year, another university has been exploring curriculum for a doctoral degree in dental hygiene for practicing dental hygienists interested in pursuing advanced education. If approved, this curriculum would include courses such as cultural competence, health information systems, proposal development, health literacy, research methods, biostatistics, evidence-based practice, writing for health professions, three courses in a concentration area (education, public health, or leadership and change), and capstone project courses.

OPPORTUNITIES WITH DOCTORAL DEGREES

For dental hygienists interested in pursuing a dental hygiene doctoral degree, there are many opportunities to enhance clinical practice. Ellen Rogo, RDH, PhD, of Idaho State University, Ann Eshenaur Spolarich, RDH, PhD, of the Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health, and I proposed numerous capabilities with this degree option including: design and administer programs to improve the oral health of the public; conduct original and practice-based research; assess effectiveness of new workforce models; advocate for changes in health policy and direct reimbursement for hygiene services; create new models of care delivery; design community health programs that improve oral health literacy; create legislation to reduce restricted access to care, expand scope of practice, and advance availability of oral health care service; assess and update clinical standards to reflect current health care needs; and provide customized, patient-centered advanced oral health care and patient self-care education to individuals in hospitals, long-term care, and home health settings.

For dental hygienists interested in pursuing a dental hygiene doctoral degree, there are many opportunities to enhance clinical practice. Ellen Rogo, RDH, PhD, of Idaho State University, Ann Eshenaur Spolarich, RDH, PhD, of the Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health, and I proposed numerous capabilities with this degree option including: design and administer programs to improve the oral health of the public; conduct original and practice-based research; assess effectiveness of new workforce models; advocate for changes in health policy and direct reimbursement for hygiene services; create new models of care delivery; design community health programs that improve oral health literacy; create legislation to reduce restricted access to care, expand scope of practice, and advance availability of oral health care service; assess and update clinical standards to reflect current health care needs; and provide customized, patient-centered advanced oral health care and patient self-care education to individuals in hospitals, long-term care, and home health settings.Dental hygienists desiring a doctorate of philosophy in dental hygiene degree will more likely find roles available in academia, research centers, and administration. Proposed experiences for graduates with this degree include conducting original research; providing foundational evidence that supports research, education, and practice; serving as gatekeepers of the scientific literature to ensure continued quality of published evidence; proposing new theory and testing existing theoretical models; continuing to build the research infrastructure of the profession; leading strategic planning initiatives to advance the profession; mentoring students and colleagues and preparing a cadre of future scholars; and creating leaders in academia, business, and health care.15

CHALLENGES AHEAD

Davis et al13 identified shortages of qualified educators to teach in doctoral programs as a significant challenge perceived by dental hygiene educators. Another concern was having enough interested individuals enrolled in doctoral programs. When one university submitted its proposal to initiate the PhD program in dental hygiene, it received internal approvals to proceed. However, the university’s president did not approve the program due to concerns about whether there were sufficient doctorally prepared faculty to teach in the program.

One option for addressing the shortage of qualified educators is to create a consortium of doctoral dental hygiene educators. This consortium could be modelled after NEXus, (Nursing Education Xchange Collaborative) a partnership among select universities offering doctoral nursing programs (both PhD and DNP) that allows students at member institutions to take courses from a collaborating institution.16 The goals of NEXus are to: reduce the costs of creating online courses; increase the choice of courses available to nursing PhD students; and overcome the administrative barriers to students enrolling in shared courses.16 In a similar manner, dental hygiene could share resources, such as educators and courses among universities, and broaden opportunities for dental hygienists to study with experts in the discipline and receive advanced degrees.

CONCLUSION

Change is the one thing that is inevitable. For some, change cannot happen fast enough, and for others it is moving too quickly. By 2025, there may well be both PhD and dental hygiene doctoral programs. What we do know is that the public’s oral health remains staggeringly poor. Childhood caries is at epidemic proportions and remains the most common infection in children.17 A higher proportion of these children live in poverty and experience adverse effects of untreated caries that can affect quality of life extending into adulthood.17 Almost half of adults age 30 and older have some form of periodontal disease.18 Sadly, almost 50,000 will be diagnosed with oral and pharyngeal cancers and 9,700 will die this year.19

The 2011 Institute of Medicine report, Advancing Oral Health in America, offered recommendations for the improvement of oral health in the US including exploring new models for care delivery.20 The profession has begun to embrace new workforce models, but other reforms are needed, including improved license reciprocity, reductions in prohibitive supervision, and expanded scope of practice.21 It is also essential to look beyond the current system of dental hygiene education. Dental hygienists need to be prepared as health care providers who will challenge prevailing thinking, test theories, lead interprofessional teams, and develop policies that will change the delivery of oral health care to improve population health. Current educational models do not prepare students to serve in this capacity. The curricular content of doctoral dental hygiene education is designed to prepare the graduate of the future to address these ongoing oral health challenges and change them. By 2025, the conversation could shift to creating a different future in oral health.

REFERENCES

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Dental Hygiene: Focus on Advancing the Profession. Available at:wsdha.com/clientuploads/pdfs/ADHA%20pdf/ADHA_Focus_on_Advancing_Profession.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Boyleston ES, Collins MA. Advancing our profession: Are higher educational standards the answer? J Dent Hyg.2012;86:168–178.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Credentialing in Pharmacy. Available at:medscape.com/viewarticle/406934_print. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice. Available at: .aacn.nche.edu/dnp/Essentials.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- American Academy of Audiology. AuD Facts. Available at: audiology.org/education-research/education/students/aud-facts. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Henson HA, Gurenlian JR, Boyd LD. The doctorate in dental hygiene: Has its time come? Access. 2008;22(4):10-14.

- Boyd LD, Henson HA, Gurenlian JR. Vision for the dental hygiene doctoral curriculum. Access. 2008;22(6):16-19.

- Gurenlian JR, Spolarich AE. Creating the doctoral degree in dental hygiene. Paper presented at: American Dental Education Association Annual Session; Tampa, Florida: 2012.

- Gurenlian JR. Summary of the International Federation of Dental Hygienists House of Delegates workshop. Int J Dent Hyg. 2010:8:313–316.

- Gurenlian JR, Spolarich AE. Advancing the profession through doctoral education. J Dent Hyg. 2013;87(Suppl 1):29–32.

- Tumath UG, Walsh M. Perceptions of dental hygiene master’s degree learners about dental hygiene doctoral education. J Dent Hyg. 2015;89:210–218.

- Ortega E, Walsh MM. Doctoral dental hygiene education: Insights from a review of nursing literature and program websights. J Dent Hyg. 2014;88:5–12.

- Davis CA, Essex G, Rowe DJ. Perceptions and attitudes of dental hygiene educators about the establishment of doctoral education in programs in dental hygiene. J Dent Hyg. 2016;90:335–345.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Transforming dental hygiene education and the profession for the 21st century. Available at: adha.org/adha-transformational-whitepaper. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Gurenlian JR, Rogo EJ, Spolarich AE. The doctoral degree in dental hygiene: Creating new oral healthcare paradigms. J Evid Base Dent Pract. 2016:16S:144–149.

- NEXus The Nursing Education Xchange. Available at: winnexus.org. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Colak H, Dülgergil CT, Dalli M, Hamidi MM. Early childhood caries update: A review of causes, diagnoses, and treatments. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2013;4:29–38.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Division of Oral Health. Periodontal Disease. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/basics/adult-oral-health/index.html. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2014. Available at seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Institute of Medicine. Advancing Oral Health in America. Available at: hrsa.gov/publichealth/clinical/oralhealth/advancingoralhealth.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Bersell CH. Access to oral health care: A national crisis and call for reform. J Dent Hyg. 2017;91:6–14.

From Perspectives on the Midlevel Practitioner, a supplement to Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2017;4(10):30-33.