PEOPLEIMAGES / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

PEOPLEIMAGES / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Addressing Dental Hygienists’ Workforce Issues

The ADHA partners with the ADA to better understand the impact of COVID-19 on the dental hygiene workforce.

COVID-19 has impacted every facet of daily living from family structure, education, income, safety, and healthcare. For almost 3 years, society has had to adapt to this virus and its variants. Likewise, oral healthcare and oral health professionals have been significantly affected by the pandemic modifying infection control practices, implementing national guidance protocols, and adding immunization procedures to their skill sets.

One adaptation that was not anticipated was the shift in employment status of dental team members including dentists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants. Worries about workplace safety, availability of personal protective equipment (PPE), and childcare needs encouraged some oral health professionals to consider early retirement or temporary/permanent leave, resulting in concerns about impending workplace shortages.

The American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) partnered with the American Dental Association (ADA) Health Policy Institute (HPI) to understand the impact of COVID-19 on the dental and dental hygiene communities. A series of national surveys were conducted to explore employment patterns, mental health issues, vaccination routines, and infection control practices. This paper will describe workforce and employment issues learned through these investigations.

Setting the Stage

Although it is easy to blame workforce problems on the pandemic, employment issues existed prior to COVID-19. For background and context, the results from a survey of dental hygienists conducted by the ADHA in 2016 need to be reviewed.1 At that time, dental hygienists were reporting workplace concerns including lack of employment benefits, inadequate appointment scheduling, low wages, and dissatisfaction with office culture. Among respondents, 37% cited lack of respect for dental hygienists in the workplace while 32% reported concern over having to clock out when a patient canceled an appointment.

In another survey conducted in 2019—before the pandemic—43% of dental hygienist respondents were considering seeking a new job within the next year due to not feeling respected or valued and not receiving acceptable compensation.2 If employment dissatisfaction already existed among some dental hygienists, consider what the threat of a deadly virus would do to those with low morale.

Viral Upheaval and Impact on Employment Status

In the early weeks of the pandemic, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the ADA recommended dental care be limited to emergency procedures only.3,4 When practices resumed their regular schedules, many oral health professionals still had questions and concerns about safety in the workplace. PPE supply chain issues were challenging but corrected over the course of the first year of the pandemic. National guidance resources were offered through the CDC, Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, ADHA, and ADA to minimize COVID-19 risks.5–9 The ADHA offered and continues to update specific guidance for each of the sections of the CDC interim guidelines, including specific guidance on screening patients, donning and doffing PPE, high-volume evacuation, use of dental assistants, and aerosol-generating procedures.9

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, dental hygienists have been recognized as one of the most at-risk nonhospital occupations due to contact and physical proximity with others and exposure to disease and infection.10 Beginning in September 2020, the ADHA and the ADA HPI began investigating how the COVID-19 pandemic was impacting dental hygienists and affecting employment patterns. The first study of this nature occurred between September and October 2020 with 4,776 respondents from all 50 states and Puerto Rico completing the survey.11

Results of this initial study revealed that 7.9% of dental hygienists (n=360) had exited the workforce since the onset of the pandemic, translating to an estimated reduction of approximately 18,000 dental hygienists from the workforce. Most of these hygienists left employment voluntarily, and their departure would likely be temporary, lasting through the pandemic. Only a small portion (0.5%) indicated they were considering permanently leaving their jobs. Further, more dental hygienists who were 65 years and older were not employed or had voluntarily left their positions. Reasons cited among those who voluntarily left their positions included not wanting to return to work until the pandemic was under control, concerns about adherence to workplace/safety standards, no longer wanting to work as a dental hygienist, and childcare concerns.11

Of the respondents who began the COVID-19 impact study in September 2020, approximately 4,300 dental hygienists volunteered to continue completing monthly surveys through August 2021. Additional dental hygienists were invited to participate over the course of this period with 6,976 participating in at least one wave of the survey. An update on the previous research related to employment patterns was examined.12

Six months into the pandemic and as of March 1, 2020, almost 8% (n=360) of the respondents reported they had left their jobs. However, when this longitudinal study concluded in August 2021, 4.9% (n=59) of dental hygienists were not employed. Like the initial study, respondents in older age groups were more likely to be working less or not at all. Reasons for leaving the workforce included retiring from practice, not wanting to work until after the pandemic is under control, and concerns about employer’s adherence to workplace/safety standards.12

In June 2022, dental hygienists were surveyed to examine issues related to sustaining and improving workplace satisfaction to refine recruitment initiatives. A total of 5,122 dental hygienists from across the US participated in this Dental Team Workforce Shortages survey. The majority of dental hygienists (71.8%) reported they were satisfied in their role with reasons including work-life balance, workplace culture, and helping patients. The top factors noted by dental hygiene respondents who were dissatisfied with their employment were workplace culture, lack of growth opportunity, inadequate benefits, being overworked, communication concerns, and insufficient pay.13

Moving Beyond the Pandemic

There are two important factors to reflect upon related to the dental hygiene workforce issue. First, the update study showed that the employment trend is moving in a positive direction. While some dental hygienists are retiring, many are working and managing the effects of the pandemic. They have adapted to infection control practices using national guidance recommendations, becoming vaccinated, and managing childcare issues more effectively.

Second, the pandemic has revealed a heightened awareness of the need for employers to address workplace issues. For example, throughout the pandemic, dental hygienists have expressed concerns about adherence to safety standards. This is a compelling issue for individuals who are concerned for their personal safety as well as that of patients, dental team members, and their families. Ignoring national guidance and not providing sufficient PPE were concerns noted in a recent study of COVID-19 practices of dental hygienists in one state.14 Implementing appropriate protocols demonstrates a commitment to safety, shows respect and value for dental team members and patients, and reduces ethical conflicts.

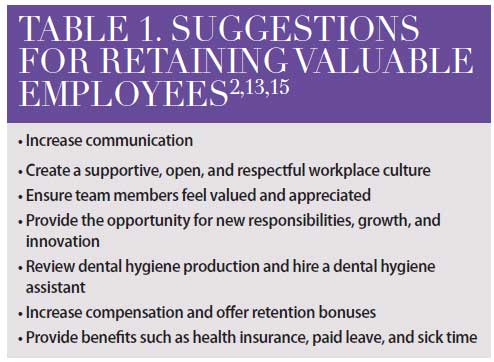

Retaining valuable employees requires increasing communication and creating a workplace culture that is supportive, open, and respectful. Team members need to feel valued and appreciated. Table 1 (page 15) provides additional suggestions for addressing dissatisfaction.2,13,15

Suggesting there is a shortage in the dental hygiene workforce is a simplistic assumption to make. However, paying attention to the data and listening to dental team members show that workplace job satisfaction is a leading indicator of the problem amplified by the pandemic. Fortunately, there are solutions and opportunities for change.

References

- Analysis of the 2016 Survey of Dental Hygienists. Chicago: American Dental Hygienists’ Association; 2016.

- Lanthier T. Survey: COVID-19 compounds dental staffing challenges.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for healthcare personnel during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

- American Dental Association. ADA recommending dentists postpone elective procedures.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infection prevention and control in dental settings.

- Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention/CareQuest Institute. Best practices for infection control in dental clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Occupational Safety and Health Information. COVID-19 control and prevention: dentistry workers and employers.

- American Dental Association Center for Professional Success. COVID-19 safety and clinical resources.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Interim Guidance on Returning to Work.

- Lu M. These are the occupations with the highest COVID-19 risk.

- Gurenlian JR, Morrissey R, Estrich CG, et al. Employment patterns of dental hygienists in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemicJ J Dent Hyg. 2021;95:17–24.

- Morrissey RW, Gurenlian JR, Estrich CG, et al. Employment patterns of dental hygienists in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: an update. J Dent Hyg. 2022;96:27–33.

- Dental Team Workforce Shortages: Data to Navigate Today’s Labor Market. Chicago: American Dental Association Health Policy Institute; 2022.

- Lane CK, Gurenlian JR. COVID-19 practices of Idaho dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2022;96:20–27.

- Levin RP. Addressing the dental hygienist shortage.

From Perspectives on the Midlevel Practitioner, a supplement to Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2022;9(10):12-14.